My local airport, Corona Municipal in Southern California, sits in the Prodo Dam basin and is known to flood on occasion. Last February, heavy rains brought much needed relief to drought-stricken Southern California. True to form, the west end of the airport (which is about 20 feet lower than the east end) flooded on the morning of the 14th.

Although I was prepared to evacuate, by the time I got the word to move, water was already inside the hangar and rising fast. When I got there, the wheels of both planes were submerged.

Despite the knee-high water and cold weather, everybody helped to get each other’s stuff moved to high ground. When the water finally receded, even more people showed up to help clean the mud from the hangars and wash down the aprons and taxiways. It’s a tribute to the bond that is aviation that airport and airplane people always seem to pull together in a crisis.

After the flood, it took the better part of a two weekends to tear apart the wheels, clean, inspect, and reassemble everything. All in all, both the Jabiru and the Victor Stanley-built Funkist (my orange and black VW-powered single-seater, aka “Tony the Tiger”) survived the flood none the worse.

Although I don’t fly the Funkist anymore—the Jabiru is faster and more comfortable—I keep it in good working order. Twice a year I run the engine and taxi it over to the EAA Chapter 494 Young Eagles event to let kids sit in the cockpit and get the feel of flight controls.

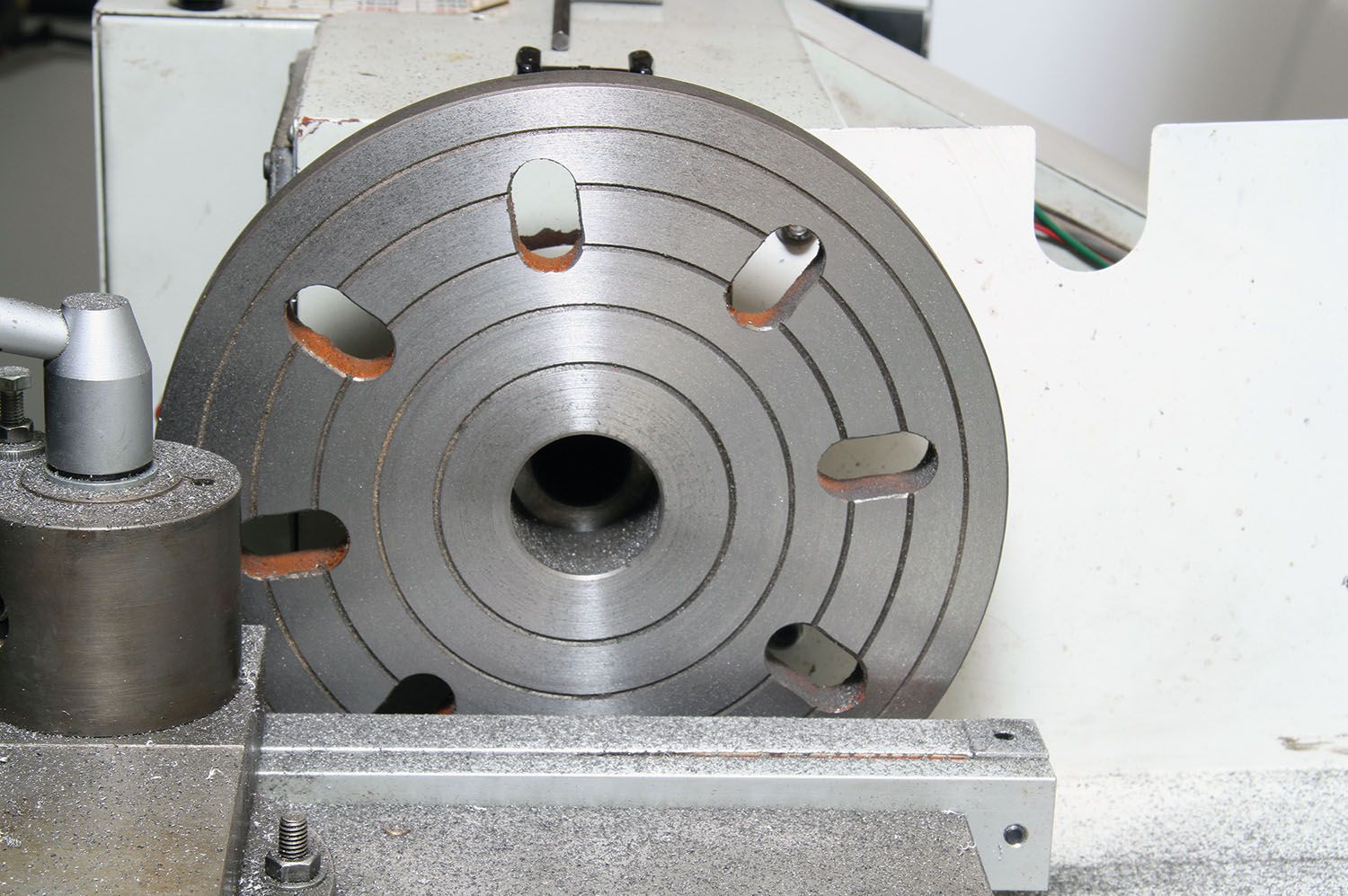

Fast forward to this summer. Despite having torn apart, cleaned, and repacked the wheels, I noticed corrosion pitting on the brake rotors of the Funkist. The combination of being submerged and then not having regularly used the brakes probably allowed moisture to linger and attack the rotors.

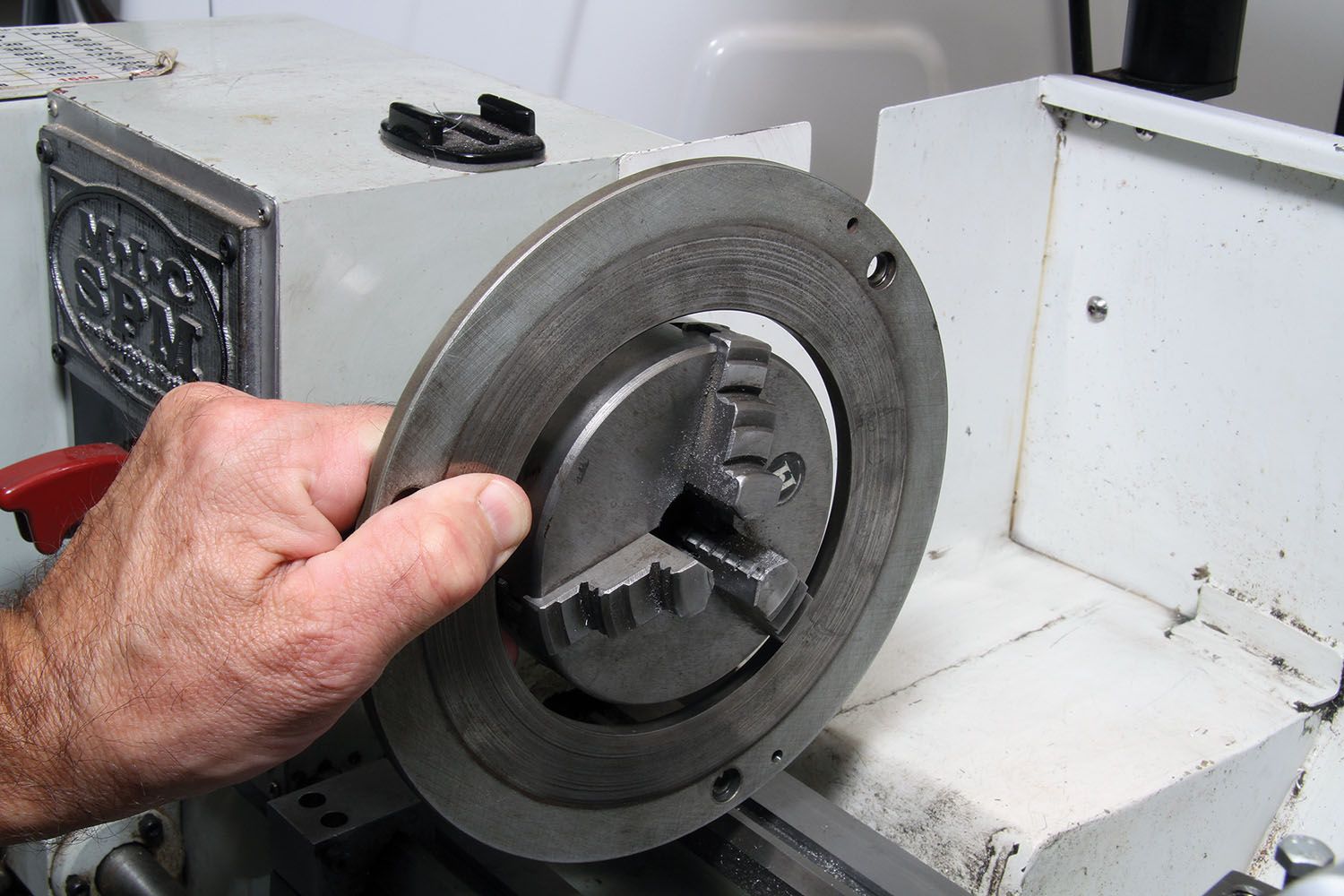

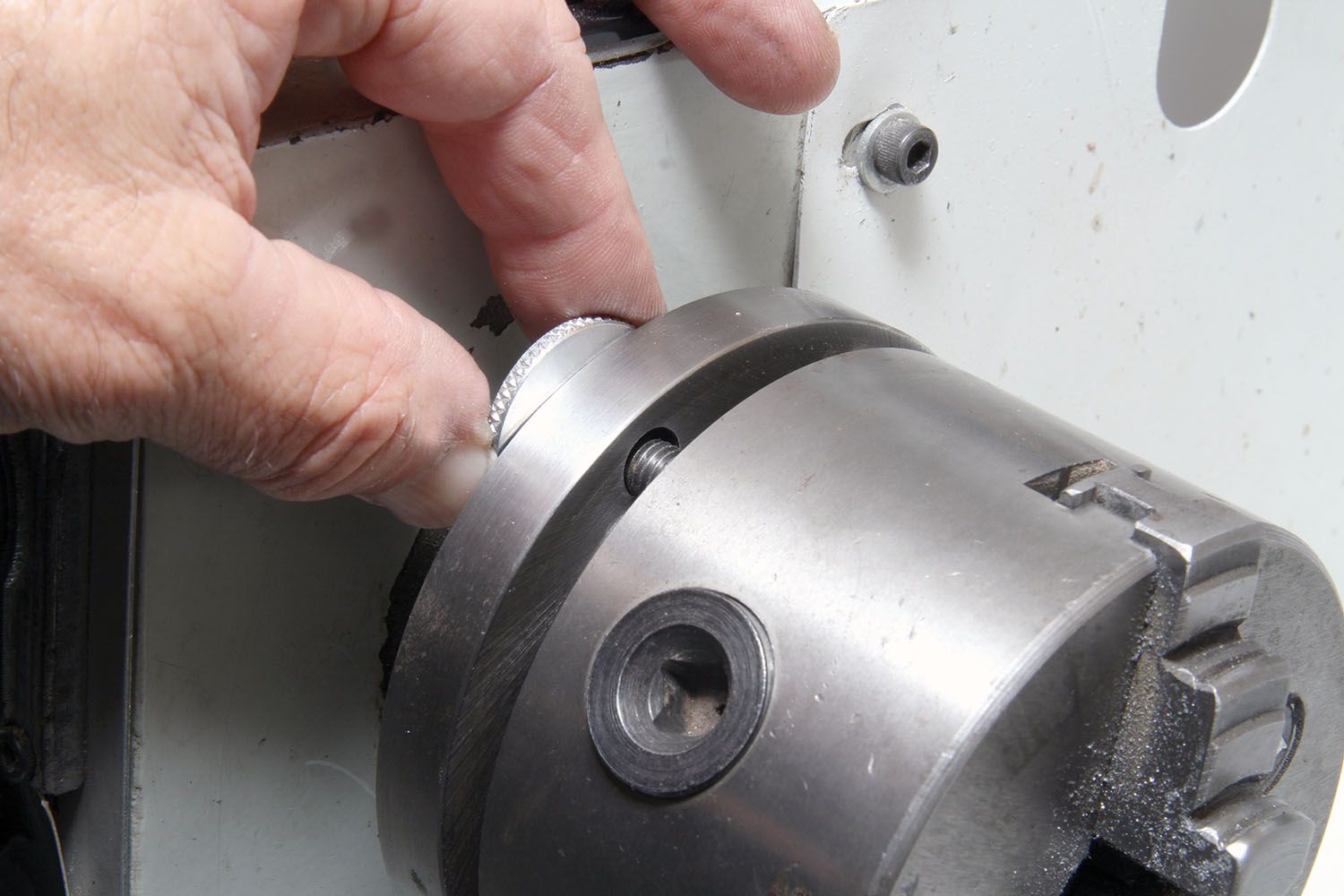

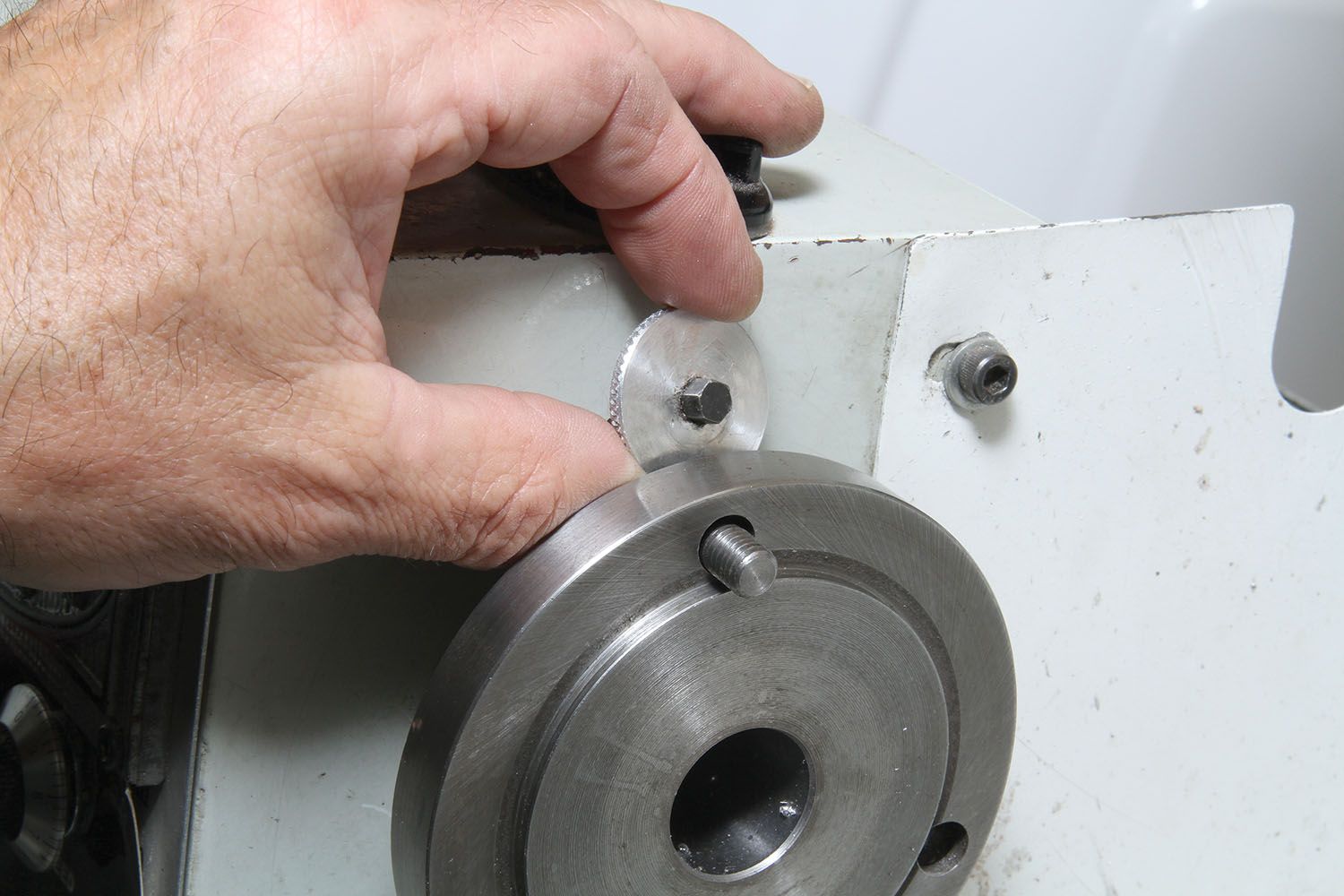

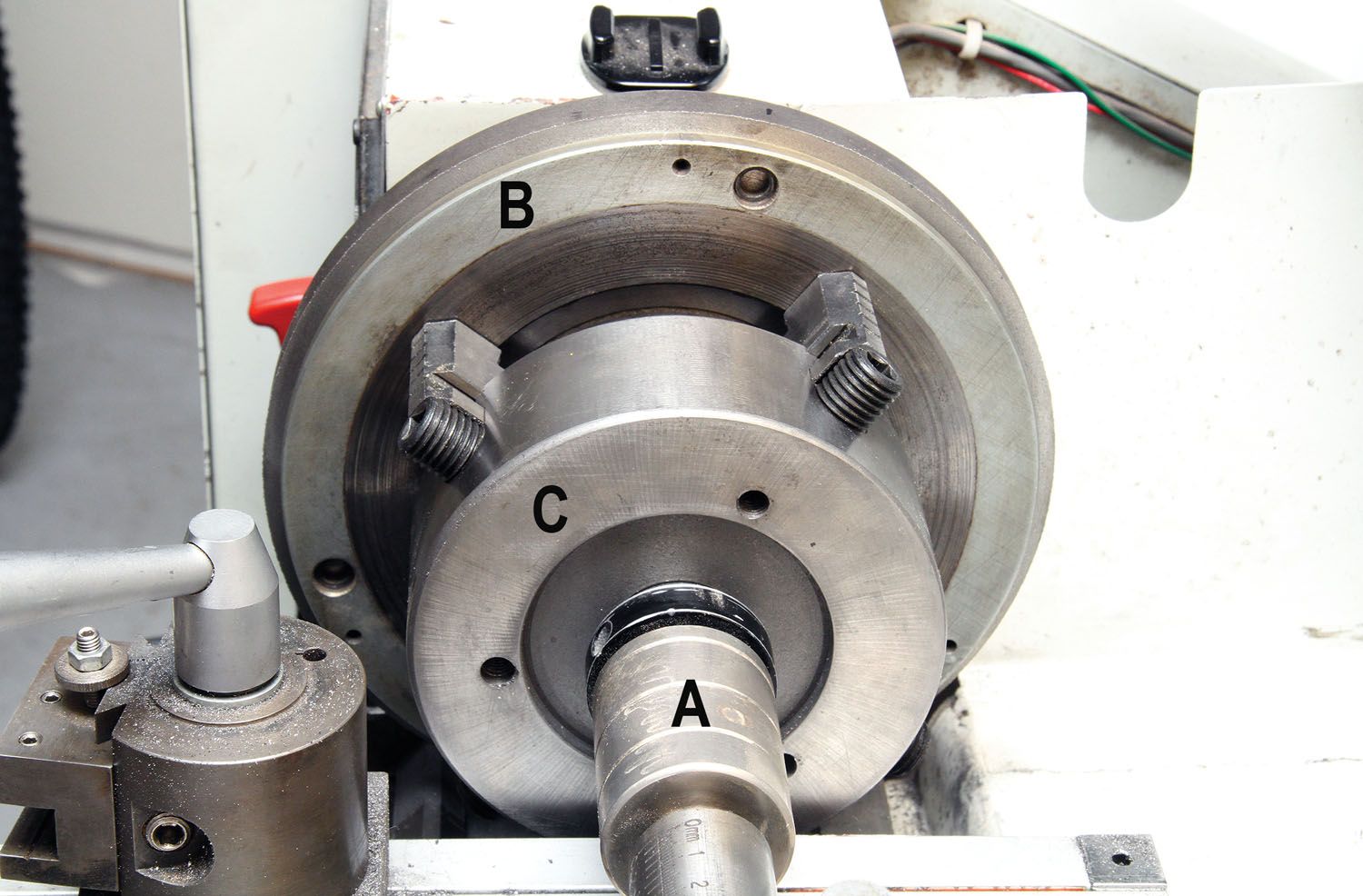

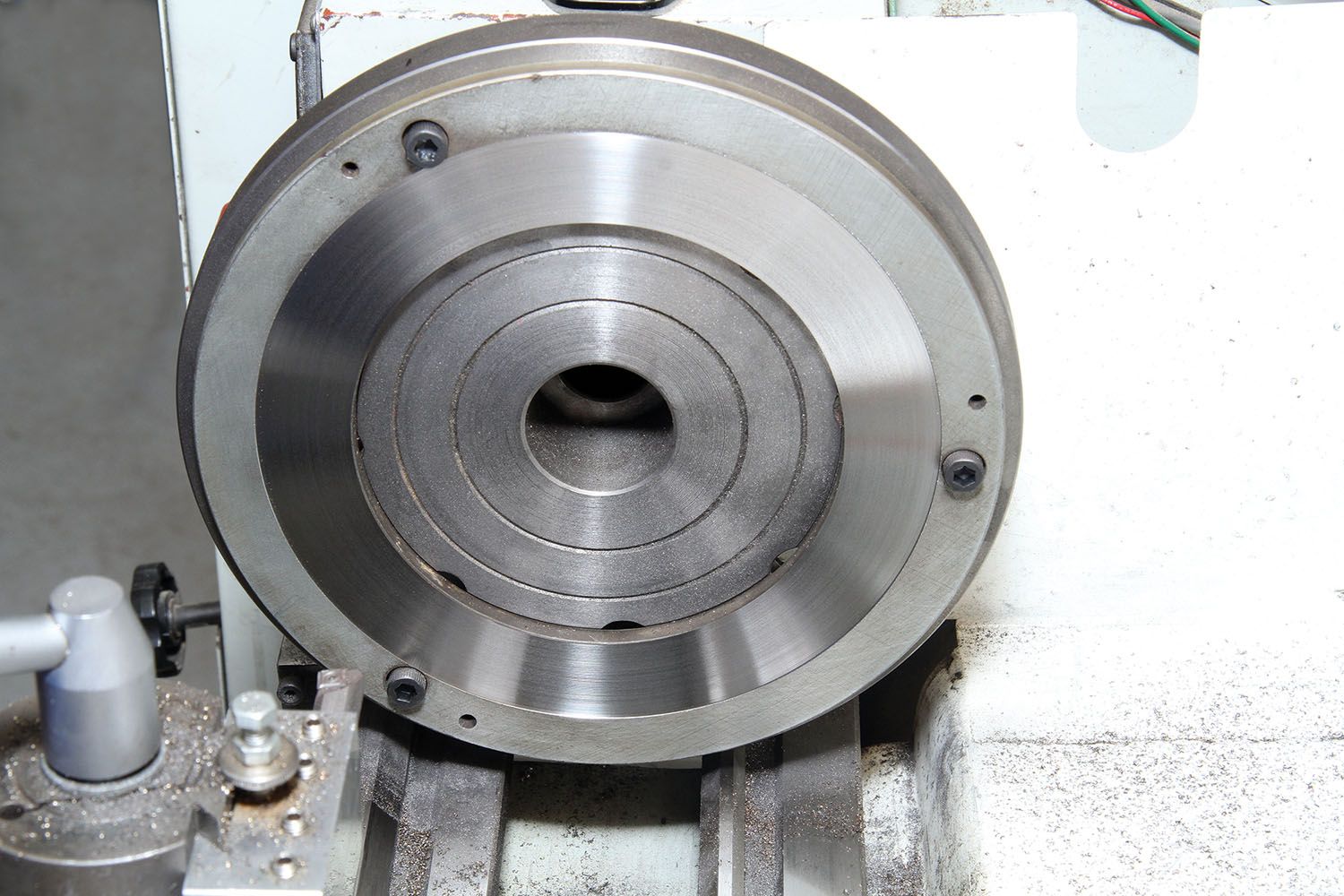

Since the brake rotors on the Funkist were barely worn, I decided to try resurfacing them using my small home-shop lathe. The brakes on my Funkist are more than 20 years old, and from an era when parts were made so they could be repaired or restored. With modern components that is sometimes not the case. New rotors may not be compatible with lathe turning, or they may simply be so thin and lightweight to begin with that when worn out, they must be replaced. Always check with the manufacturer for wear limit (minimum rotor thickness) and approved procedures. If the information is ambiguous, contact the company and ask. The experimental aircraft community is super-friendly, and if you have a question, manufacturers want you to reach out to them.

It’s been said that airplanes don’t like to sit unused. After making the effort to clean up the brake rotors, I’ve resolved to get the Funkist out more than twice a year, not just for the brakes but to make sure all the systems get a good workout. Who knows? Maybe someday a Young Eagle might end up owning “Tony the Tiger.” In the meantime, it’s time to get out to the shop and make some chips!