After storing the finished wings and cleaning up after the wing-finishing party (i.e., washing a trio of beer steins), the Pudding River Bearhawk crew—Rion Bourgeois, Philip Groelz, and I—sat down to contemplate our next step. Now that the major sheet metal assemblies of the Bearhawk LSA were behind us, Rion and I were truly out of our comfort zone as we rubbed our chins and reviewed the plans for the welded steel tube fuselage. Fortunately Philip, who’s built a Wittman Tailwind and a Christavia, was not intimidated. He understood exactly what we were about to undertake.

There are a lot of pieces of steel tubing in a Bearhawk fuselage—the plans include a table detailing 14 different tubing diameters and wall thicknesses. (As we built the fuselage we found another 12 sizes noted on the plans that weren’t included in that chart.) Some of the joints had as many as eight tubes coming together in one place. Joining four or five tubes was fairly common. This meant that the ends of every tube had to be “coped” or cut at an angle that let it meet all the other tubes. If you mis-cut a tube, you either had to find a place where a shorter tube of the same dimensions was required, or just chuck it.

“Look,” Philip said, as Rion and I held our heads and moaned. “Thousands of airplanes have been built this way, and coping isn’t that difficult. It doesn’t have to be microscopically accurate—in fact, you can do a lot of it with hand snips. There’s even computer programs on the web that will compute the angles and print a cutting guide you can wrap around the tube.” [See “Tube-Notching Made Easy,” KITPLANES, April 2015.]

Well, that didn’t sound too hard, so we found a few short tubes in Philip’s scrap bin and tried various methods of coping—snips, bench grinder, Dremel tool. Sure enough, it was doable and with practice it improved. But that didn’t change the fact that there were a lot of tubes…I was beginning to see why so many scratch-built rag/tube airplanes were never finished.

Then a faint glow on the southern horizon illuminated a solution. Mark Goldberg’s Bearhawk kit facility in Mexico had just begun producing welded LSA fuselages in both basic and advanced versions. Although a completely welded fuselage was outside our financial reach, Mark agreed that he could offer a “flatpack” kit, with all the tubes cut and coped, but no welding done. The price he quoted seemed reasonable—in fact, figuring in the inevitable waste we’d create doing our own, the kit was probably cheaper than we could achieve buying small lots of tubing and doing the work ourselves.

We ordered the kit and received the second one shipped. It was one of the better decisions we’ve made on the project. When the kit arrived, the packaging was somewhat the worse for wear, but the contents were undamaged. It was well organized, complete, and—as we were to find when we started assembling it—very accurate. Those guys in Mexico knew their stuff!

MIG or TIG?

As we inventoried the tubing kit, we faced our next major decision—who was going to weld this beast? Rion had no welding experience at all, and I had just a bit of training and practice a few years ago. Philip was the obvious choice, having done a lot of oxyacetylene welding on his previous aircraft and owning a large TIG welder. However, during the Christavia project, he’d decided on a different approach. He used a MIG welder to tack his components, then hired a professional welder from nearby Van’s Aircraft to step in and do the finish welding with the TIG machine.

“It was the best combination of time and money,” he said. “I would spend several hours getting structures tacked together, then the hired gun would step in and in an hour or two there would be this completely welded component—and not only was it quicker, but the welds were far, far better than I could do. There’s just no substitute for those thousands of hours of experience.”

I really didn’t want to do it that way. After all, this was probably my last chance to say, “Yeah, I built that,” and know that I really had. If that meant learning how to TIG weld to an airworthy standard, I’d just have to practice until I could. In the past I’d learned how to throw pottery on a wheel (I’ve made at least 8000 coffee mugs!) and do professional-level calligraphy. I didn’t learn any of that because I had any talent. I’d learned it through dogged repetition and focused practice. I knew that I could (slowly) teach my hands and eyes to learn a skill. Bring it on…

Then I re-thought the situation: If I wanted, say, a set of dinnerware, did it really make sense to spend a year learning how to throw, glaze, and fire stoneware, just so I could say I did it? How much waste, frustration, and expense would that one dinnerware set cost, and how much satisfaction would it provide? Pottery, in my case, became a profession, so the time spent learning was a useful investment. I had no intention of becoming a professional airplane welder.

I looked at my practice welds and looked at the superb quality of the steel parts in Van’s RV kits, and I knew that it would take hundreds of hours of practice to close the gap. None of those hours would improve my partners’ experience with the project, I’d waste a substantial quantity of steel, and no doubt months of time. That’s a high price to pay—and make my partners pay—for ego gratification.

So we winched Philip’s TIG welder—about the size of a small refrigerator and the weight of a cast-iron V-8!—into Rion’s trailer, tractored it down to the Taj MaHangar, installed a new 220-volt line, ran some hoses in for the water-cooled torch…and hired Sam Hill.

Smart Move

Working with Sam turned out to be another good decision. He’s been a production welder for Sherpa Aircraft and Van’s for a decade or more. Since we are just a few miles from Van’s factory, he could usually make it over to our place after his workday ended, and in an hour or two he’d weld up everything we’d prepared in several work sessions.

The basic fuselage went together quite quickly. “Let’s enjoy it while we can,” Philip counseled. “Nothing else on the airplane will make so much ‘show’ in so little time.”

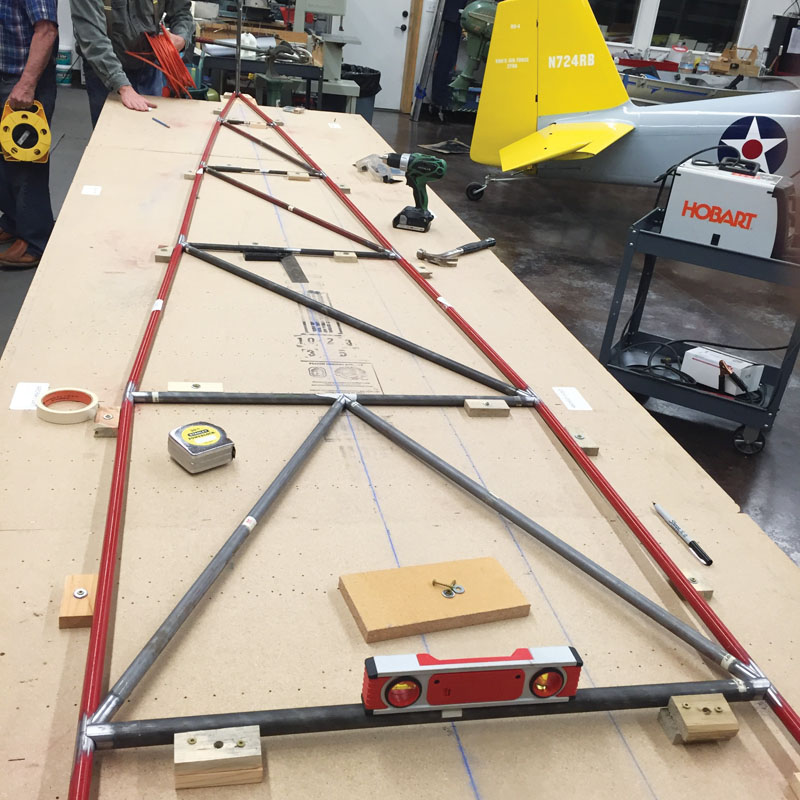

Construction began by snapping a centerline down the 16-foot table we’d used for the wings. It was a bit short of ideal, but we found that we could make it work. The top and bottom of the Bearhawk fuselage are welded first, then the top is suspended above the table. Both assemblies are aligned with plumb bobs, and the vertical pieces are inserted, starting at the tail post and working forward to the firewall. Our job was to clean the tubing ends to bright metal and rig up whatever Rube Goldberg arrangement of boards, clamps, and drywall screws would hold them in position. Sam would then come in and make beautiful welded seams around even the most complicated clusters. The MIG tacking idea was only marginally useful on some of the really thin-wall tubing used to keep the airframe light, so in many cases we just adjusted the tubes with a gloved hand while Sam welded. We used welding hoods and long-sleeved shirts as well, to protect our eyes and skin from the radiation the welding arc produced. Rion found that he had to shut down the computers in his adjoining legal office before we fired up the welder—evidently it produced some sort of radiation that caused problems with their operation. (Sadly, it did not interfere with Rion’s shop stereo. Philip and I are fans of classical music. Rion listens to…well, I’m not sure exactly what you’d call his mixtape, but it ain’t classical! But the hangar is well-lit, it’s heated, it’s full of tools…and it’s Rion’s. So we listen. Perhaps it will broaden our horizons. Perhaps.)

In about three months we had the basic fuselage welded together. Philip was certainly right. Compared to the wings, this was lightning fast. When Sam raised his hood after the last weld we all hoisted a glass to another milestone.

The next day the reality of this type of construction set in…the basic trusswork fuselage is just the beginning. There’s probably twice as much time in adding fittings and brackets for the wings, landing gear, tail surfaces, boot cowls, formers, and windows. The control system conforms to designer Bob Barrows’ evident philosophy: “There’s no need to weld four little pieces together when you can weld five!”

Next time we’ll explore the world of small pieces and how they’re made. Believe me, there are lots of opportunities to learn…

Glad to see the pin hole for the expanded gases to purge out! Unfortunately some forget.

Or is that hole to enable you to add oil to the inside of the tubes after welding to prevent corrosion ?

I was hoping when the heading said ‘MIG or TIG’ you were going to discuss the pros and cons of each system ….