As I go through our back issues for our Archive page and relive the world of homebuilding in the 1980s (and, by extension, even before that), it strikes me how far we’ve come. Once considered true outliers, somewhat crazy craftsmen/renegades building flimsy contraptions in their basements from nothing more than discarded two-by-fours and swing set parts—not true, of course—homebuilders are now tantalizingly mainstream. On any airport of a certain size, there will be an airplane being begun or readied for first flight—and anywhere in between. On mine, there are many.

In those early days, homebuilders took what they could get. Used engines, often from wrecked Cessna 150s or Cherokees, rebuilt for our needs. Avionics found at the local fly market ready for a second lease on life after the Bonanza owner upgraded. In those days, there was no dedicated product or heavily strategized marketing plan for Experimentals. We roamed the boneyards and airshows looking for deals, also spinning by the local airport bulletin board hopeful to find a 3×5 card thumbtacked there on the cork, promising some dream component.

Now, However

It’s a whole different thing today. I was lucky enough to watch this emerge through the 1990s: a strong, Experimental-first product set that fully leveraged the freedoms we have as designers and builders. This is how we got custom engines from the big manufacturers. This is how companies like TruTrak Flight Systems, now part of Honeywell and BendixKing, got started. This is why, for years, pilots of certified aircraft peered through the canopies of parked RVs and Lancairs and pined for the advanced, lightweight, low-cost avionics they saw. We all sort of know this without thinking too hard about it.

The reason I bring it up here? Over the last few weeks, I’ve been in the process of testing new products in my GlaStar. (Once begun, this process never stops. Paul Dye warned me, and yet I failed to heed!)

Part of this latest round has involved fitting Garmin’s new GI 275 round instruments. I’ll give you a full review once I’ve finished this work and have enough flying time to form a full opinion, but let’s say the installation process—equal parts wire cutting and book learning, it should be said—has been more than a little interesting. What’s more, this endeavor has answered my initial question about why the new Garmin boxes are expensive relative to the existing product for Experimentals.

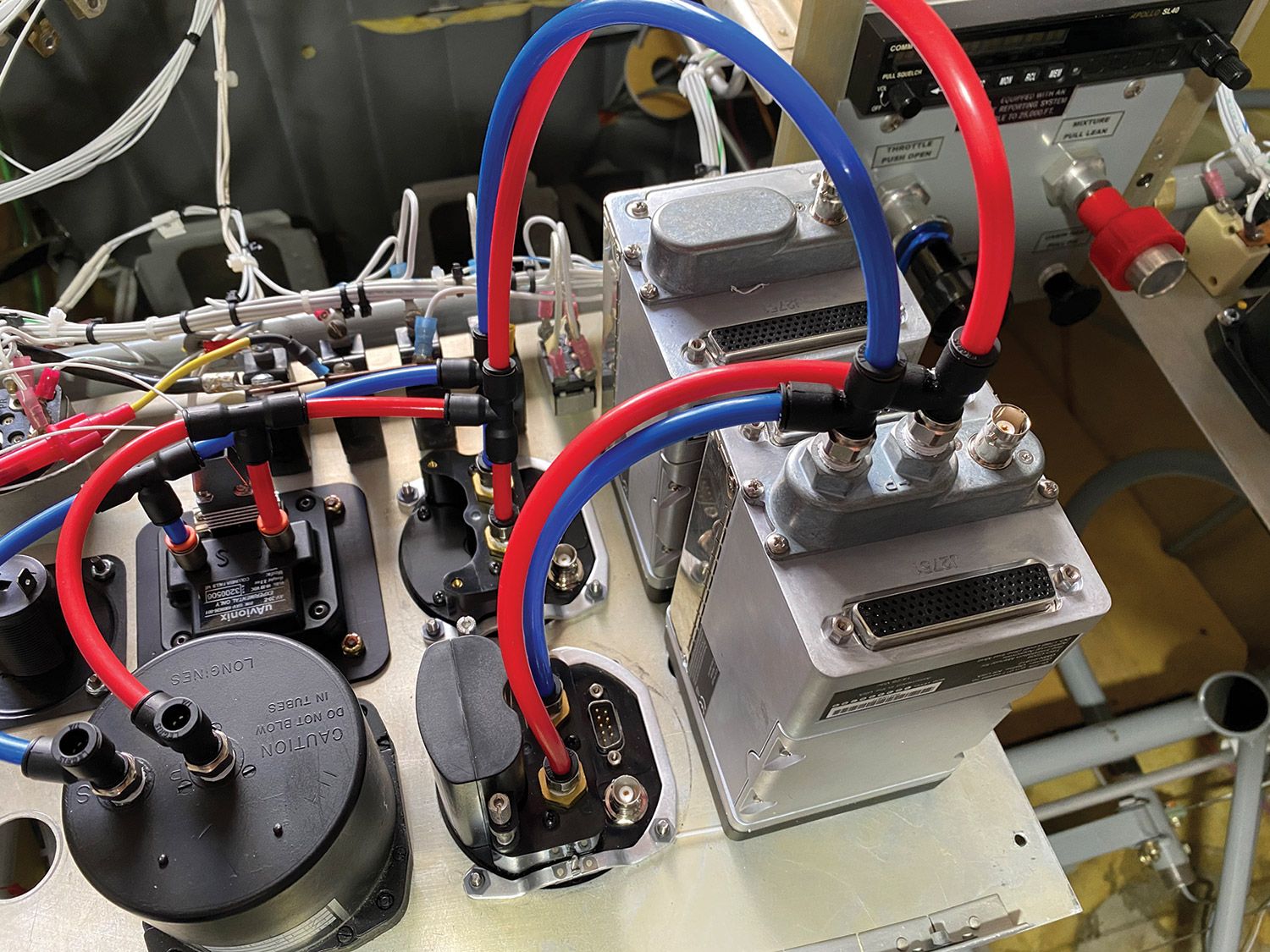

This answer came as the differences were laid bare in one image. In the process of wiring and plumbing the panel, I had two GI 275s mounted next to a pair of G5s and saw, from the back, just how radically different these instruments are in terms of approach. The G5 is light, compact, mostly plastic. It’s inexpensive for what it does and has been, in my experience, thoroughly reliable. It’s not very deep and can be readied for use with little more than connections to power, ground and the pitot-static system. Even the GPS antenna is built in. The G5 reflects Garmin’s apparent belief that it could go in any aircraft, from simple lightweights to high-end stuff as a backup to larger glass. I hasten to call the G5 toy-like, but it was clearly designed with cost, complexity and low weight in mind.

Now look at the GI 275. It’s a tank. With a die-cast aluminum case, hearty bezel and thick knobs with we-mean-business detents, the 275 feels ready to go into a King Air, which, well, it is. The battery module—optional for the non-essential flight displays but required for the primary attitude version—snaps into a slot with a satisfying thunk, is bolstered by rubber stoppers and fits under a tight-fitting, metal cover. I once had a Beech Bonanza with older Collins radios and looking over the GI 275 reminded me of how overbuilt certified avionics can be. At 3 pounds, the GI 275 with internal ADAHRS is three times the weight of a G5. It’s also longer, though not as deep as the cranky old vacuum DG that I’m finally kicking to the curb.

More telling than the length of the install manual, nearly 500 pages, are the ways the GI 275 talks to the rest of the airplane. In the G5, reflecting the much more open architecture found in homebuilts, a CAN bus system (two wires) communicates with external modules, including outside-air temp, a remote magnetometer, an ARINC 429 convertor (necessary with an IFR GPS), a remote autopilot control panel and the servos themselves. The understanding is that modern Experimentals aren’t going to have much if any legacy equipment. (I suppose there could be a homebuilt running around with a repurposed Cessna 300-series autopilot, but I haven’t seen it.)

Part of the 275’s complexity is that Garmin has accommodated all manner of existing infrastructure, including newer and ancient autopilots, various navigators and other pieces of vintage equipment likely to be in an older certified airplane. The 275’s architecture also eschews most remote modules—the OAT probe connects directly into the unit, for example, and each 275 model has both ARINC 429 ports and Ethernet (also called HSDB, or high-speed data bus). In practice, one GI 275 can connect directly to a modern navigator with just four wires to share nav and EFIS/air-data back and forth, seamlessly. It can take that info and output analog signals to autopilots and accept analog signals from older navigators. It is, from both design and execution standpoints, an amazing device.

And So?

Imagine that the Experimental sub-market for cool, innovative products never materialized. Then imagine ogling an instrument like the 275 and wondering how it might fit into our machines. Imagine teaching yourself how to manage a pair of 78-pin high-density connectors when your day job isn’t as an avionics installer. Imagine your dismay upon discovering that you’re using only a fraction of the instrument’s capabilities, but paying for them all. You don’t have to, and that’s my point. Sometimes you have to look back to appreciate how good we have it. The profusion of Experimental-only (or Experimental-first) products is, when you think about it, fairly out of proportion to the number of aircraft out there. (See Ron Wanttaja’s piece on Page 44 for more on homebuilt registration numbers.) We are all the beneficiaries of relatively low-cost, high-capability pieces for our aircraft—engines, accessories, avionics, all of it. As much as I love to renew my understanding of homebuilt innovation in its early days, I’m in absolutely no rush to go back.

Hi Marc,

I enjoyed your article and love the photo of your pitot/static plumbing and what a believe is mostly Parker Legris LF3000 series fittings. I was wondering about the termination of the tubes at the round instrument with what look like running-T’s. Is there a plug, or is there something missing – like more tubing that just isn’t in place?

Thanks.

Richard Howell

Sequim, WA

Hi, Richard. Correct. Those two connections at the analog ASI are where the pitot and static lines come in to the panel. The panel hinges on the lower support rail, so these have to be disconnected to gain access.

Marc