Ed Zaleski uses a torque wrench to tighten the engine-mount bolts on a Sportsman’s engine.

If you are building an airplane, it’s probably safe to assume that you have basic mechanic’s tools. Obviously, an assortment of wrenches, sockets, pliers, screwdrivers and such are required to install an airplane engine. But in addition to these basic tools, there are some specialized tools that you will need and some new materials that you will want to become acquainted with. Here are some of the special tools you’ll want to have during the engine installation and flight-test period.

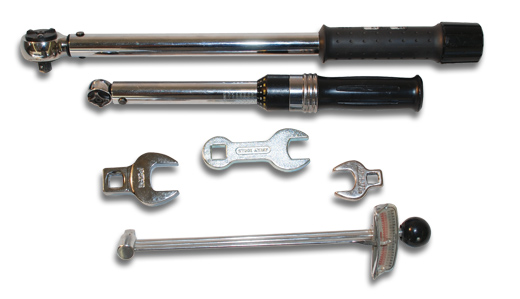

Torque Wrench

A good torque wrench is a must for proper airplane assembly. For many tasks, a ¼-inch drive torque wrench is handy, but it will not be big enough to torque spark plugs or propeller bolts. You can buy two torque wrenches if you like, but it is more economical to buy one 3/8-inch drive tool that will cover everything. Smaller bolt torque specifications are usually listed in inch-pounds, but many 3/8-inch wrenches are calibrated in foot-pounds. The conversion is simple. Just remember that 12 inch-pounds equal one foot-pound.

An assortment of torque wrenches (top to bottom): 3⁄8-drive adjustable torque wrench that will handle up to 75 foot-pounds,1⁄4-drive torque wrench for smaller items, various crow’s foot wrenches and Hartzell prop tool, beam-type torque wrench.

Torque wrenches come in two basic types: beam-type wrenches and clicking, or adjustable, torque wrenches. There are now electronic wrenches too, but having a battery in what for most people is a seldom-used tool seems likely to create frustration. The beam version relies on the bending of a steel beam to determine torque. A pointer shows torque on a fixed scale attached to the beam near the handle. These tools are inexpensive and reliable, but they can be hard to read if the item being torqued is in an inconvenient location.

A torque wrench with a Hartzell prop tool is needed to install Hartzell compact hub propellers. The Hartzell tool adds 3 inches to the overall length of the torque wrench.

With a clicking torque wrench, you can choose a specified torque and then use it like a normal ratchet handle until it clicks, at which point the proper torque has been applied. This type of wrench is more expensive than the beam-type wrench, but it is easy to use in almost any position, so it’s popular. One or the other of these is a must-have tool.

When it comes time to torque your prop, you may need a crow’s foot or a Hartzell prop tool, which is like a long crow’s foot. These special tools attach to the torque wrench and allow you to apply torque to the bolts on constant-speed propellers or on other fasteners where a socket will not fit. When using a crow’s foot, you will need to adjust the torque setting to compensate for the added length that the crow’s foot contributes.

Here is the formula for setting your torque wrench with a crow’s foot extension on it:

Tw = wrench torque setting

Ta = torque to be applied to nut or bolt

L = length of torque wrench

E = length added to wrench by crow’s foot extension

Tw = (Ta x L) / (L + E)

An example: Suppose you wish to apply 50 foot-pounds of torque to a propeller bolt. What wrench setting should be used if the torque wrench is 13 inches long (center of ratchet to center of handle) and the crow’s foot extension adds 3 inches to the length of the wrench?

Tw = (50 x 13) / (13 + 3)

Tw = 40.6 foot-pounds

Torque settings for standard nuts and bolts can be found in AC43.13-1B/2B, which every airplane builder should have. For torque settings on oil filters, spark plugs, propeller bolts and more, consult the product manufacturer.

A timing indicator, piston stop and magneto timing light allow you to check and adjust your magneto timing. The timing light is a must, but the pointer is something you can make inexpensively yourself.

Magneto Timing Light and Ignition Tools

If your engine has one or more magnetos, you will need a magneto timing light. These are readily available from most aircraft tool and supply vendors for less than $50. An automotive timing light will not work as a substitute, nor will a standard electronic multimeter. The magneto timing light allows you to set the timing of the ignition system so that the spark plugs fire at the proper time. This timing should be checked at least yearly and any time you work on the magnetos. Even with a factory-new engine, you should check the timing before you start the engine for the first time.

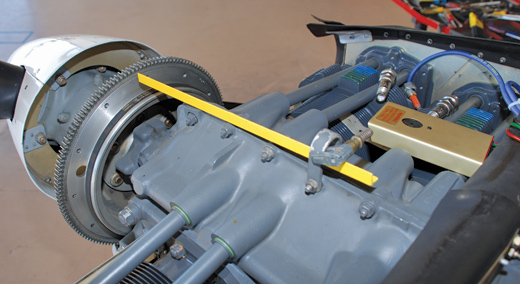

A pointer can be made from some scrap aluminum angle to indicate the crankshaft position for setting the magneto timing.

A timing indicator can be attached to the spinner after finding top dead center with a piston stop. The degree markings allow you to determine the proper magneto timing.

Along with the timing light, some mechanics use a timing indicator and piston stop. The piston stop allows you to determine top dead center accurately, and the timing indicator mounts on the prop spinner to show exactly how many degrees the crankshaft has rotated from TDC. As an alternative, you can make an inexpensive pointer that uses the marks on the back of the starter ring gear. A timing indicator and piston stop cost about $75, whereas the pointer can be made out of some scrap aluminum angle for next to nothing. The indicator and stop are nice to have, but not crucial.

Spark-Plug Tools

Unless your engine has been converted to run automotive spark plugs, you will need some aviation spark-plug tools. These include a spark-plug socket for 18mm aviation spark plugs, spark-plug gapping tools and a spark-plug caddy. Spark-plug cleaning tools are also helpful, but these are really beyond the scope of installing an engine. Note that massive-electrode spark plugs require different gapping tools than fine-wire spark plugs. Be sure the tools you buy match the plugs in your engine. One item you also need, which is not really a tool, is spark-plug thread anti-seize. A small bottle of Champion 2612 anti-seize sells for less than $8 and lasts for years.

A differential compression tester fitted with a Lycoming-recommended 0.040-inch orifice is required to do a differential compression test. You will need this for your yearly condition inspection and possibly to check out a used engine, should you want to buy one.

Differential Compression Tester

A differential compression tester is a must-have tool, but it is not really necessary for engine installation. The initial yearly condition inspection marks the first time this tool will be needed, but it probably will come in handy before then, especially if you are looking at buying a used engine or if your engine does not start out running well. Lycoming Service Instruction No. 1191A describes the proper way to do a differential compression test and specifies the orifice that must be installed in the tester for the readings to be valid. Fortunately, most new testers come fitted with this orifice, but it is best to check if there is any doubt. Note that Continental has different guidelines for performing this test.

Every airplane builder should be equipped with the tools and knowledge to properly do a differential compression test.

Engine Hoist

Buying an engine hoist may not make much sense for most builders, but it is a helpful tool for an EAA chapter to own and share. On the other hand, once you have one you will likely find other uses for it, and a hoist can often be purchased on sale from Harbor Freight Tools for about $100. If you rent one more than twice, you will spend that much and might as well own it.

A Harbor Freight engine hoist with an IO-360 engine going into a Van’s RV-8.

When using an engine hoist, don’t leave it unattended with the engine hanging on it. Hoist cylinders do sometimes leak, which could allow the engine to come to rest on the floor or whatever is underneath it. If you decide to forgo the engine hoist and hang your engine from a beam in your garage or hangar, make sure the beam will provide sufficient support. It would be really unfortunate to have the beam and the engine come down on your project.

JET sheet-metal tool: combination shear, brake and roller. A bit of an extravagance, surely, but it’s handy.

Sheet-Metal Tools

If you are building a metal airplane, or one with significant sheet-metal structural parts such as an RV or a GlaStar Sportsman, you already have all of the sheet-metal tools you might need to fabricate the baffles, firewall and cowl parts for your firewall-forward installation. However, if you are building a wood, composite or tube-and-fabric plane, you may need to borrow or buy some basic sheet-metal tools. These will include many or all of the following: pop riveter, pneumatic rivet gun and bucking bars, sheet-metal shears, shear/brake/roller, seaming pliers, drill motor and bits, step drills, chassis punch or hole saw, power saw with metal cutting blades, Dremel tool or die grinder, deburring tools, Scotch-Brite wheel, files, Clecoes and Cleco pliers. That is a lot of money to spend if you are only making a firewall and engine baffles, so borrowing makes sense, if that’s an option. Here is where your local EAA chapter could come in handy. You may also be able to find some people to help you. Most of these tools are readily available from your favorite aviation supplies vendor such as Aircraft Spruce, Wag-Aero or Wicks. Your local home center or hardware store can also supply some of the more generic tools.

Sheet-metal tools you will likely need to complete your firewall and engine-baffle installation: rivet gun, bucking bar, hand rivet squeezer, pop rivet tool, hand seamer, sheet-metal shears (right and left), Clecoes and Cleco pliers.

Unibits or step drills in a few different sizes come in handy. It is much easier, when drilling large holes in sheet metal, to start with a small hole and step it up with a step drill than to try and work with a large-diameter bit in thin sheet metal. But for really large holes (over an inch in diameter), a chassis punch or hole saw is preferred. The biggest firewall hole is usually reserved for the cabin-heat valve, which will be 1½ or possibly 2 inches in diameter. Another place where you will need to make a big hole is in the baffling where you take off air for the oil cooler. These holes are best cut with a hole saw rather than a chassis punch. It’s not that a chassis punch won’t work, but 3- or 4-inch chassis punches can be expensive. Any inexpensive hole saw will cut through aluminum baffle material fairly easily, but you will need a good hole saw and some patience to go through stainless steel.

A hole saw or chassis punch provides a good means of making holes in baffles and firewalls. The hole saw should be used only with a slow-turning drill motor.

You may find cutting the harder stainless steel or titanium alloys for your firewall is too much for sheet-metal shears. In that case, you will need to use a power jigsaw, reciprocating saw or metal-cutting band saw. You also will want some fine-tooth blades and cutting fluid. For safety, invest in gloves to keep from filleting your fingers on the sharp edges. You can deburr the edges with a bench-top belt sander and some files; a Scotch-Brite wheel on a bench grinder will also work well. Be sure to wear safety glasses when using the sander or grinder.

A hole saw works well for cutting a 2-inch hole in the aluminum engine baffle.

Depending on how many bends you need to make, a hand seamer or the edge of your workbench may suffice. However, if you have the budget to indulge yourself a bit, a combination shear/brake/roller such as the one made by JET Tools is handy to have. The 30-inch model costs about $700, so it is definitely an extravagance. However, if you get a complete baffle kit such as the one offered to Glasair Sportsman builders, you will have little need for any fabrication tools.

The author uses a metal-cutting band saw at Glasair Aviation while building his Sportsman 2+2. It’s not a required tool, but it is nice to have.

Electrical Tools

You don’t need a lot of electrical tools, but the ones you get should be high quality. Ratcheting crimpers for various connectors are preferred over the simple squeeze tools. Some connectors will require specialized crimpers. B&C Specialty Products, the makers of alternators and voltage regulators for aircraft, has some reasonably priced electrical crimpers for many of the connectors you may want to use.

Good wire strippers and wire cutters are also essential, and, fortunately, they are not expensive. A good soldering iron can be handy, but it is definitely optional. As a general rule, soldered joints are not recommended on airplanes. That said, there always seem to be a few places where solder joints just work better. Avoid them when you can, and be sure to get some training on how to do them correctly if you must.

Strippers, ratcheting crimpers and wire cutters are essential electrical tools for any airplane builder. These crimpers are set up for AMP connectors, but other types of jaws are available.

Heat-shrink tubing helps to make well-supported connections on your electrical work. It’s preferable to shrink this tubing with a heat gun rather than trying to use a match or a hair dryer. Heat guns are not expensive, so it is best to use the proper tool for the job.

A multimeter is good for tracking down electrical problems.

Lastly, a good multimeter (volt-ohm meter) is useful for tracking down problems. You don’t actually need one to install the engine if everything works correctly the first time; you will only need one if it doesn’t. The best meters are made by Fluke, but the better meters by Craftsman (Sears), Ideal and a number of other manufacturers will also work. If volts and ohms seem like Greek to you, try to get someone to help you understand how to get value out of your multimeter. Electrical problems can be frustrating if you don’t know how to track them down, but they are usually easy to fix, once identified.

A heat gun and shrink tubing make electrical work more secure and professional looking. Heat guns are inexpensive and work much better than hair dryers for shrinking tube.

Oil Filter and Oil/Fuel Line Fabrication Tools

You will need a way to remove and replace your oil filter and properly torque it. An oil filter torque wrench (preset to 17 foot-pounds) is handy, but you can also get a 1-inch crow’s foot for your torque wrench. An oil-filter cutter is a must for opening up your filter after each oil change. (Don’t even think about throwing away that old filter without making sure there are no traces of metal in the media.) Once the oil filter is properly torqued, it needs to be safety-wired into place, thus safety-wire pliers need to be in your toolbox. An oil-filter drain tool is convenient, but not mandatory. It can help minimize the mess when removing the oil filter.

Oil-changing tools include an oil-filter torque wrench, oil-filter cutter, safety wire, safety-wire pliers, side cutters, utility knife and a pan to catch the oil and to later examine the oil filter element.

A Dremel tool and cutoff wheels have many uses when building an airplane. In firewall-forward work, the Dremel tool is useful for cutting fuel and oil lines, especially stainless-steel braided hose. With different tools inserted, it can also be used to enlarge or deburr holes or cut and shape fiberglass.

GlaStar owner Tom Fleming uses an oil-filter cutter to check the oil filter for any signs of metal after an oil change.

Some types of hose, such as Aeroquip 303, require special mandrels for proper assembly. These are good items to buy as an EAA chapter or with a group of friends. They are a bit expensive for something that will not get much use. Adel-clamp tools and band-clamp tools for fire-sleeve installation round out our assortment of hose-fabrication and installation tools.

An Adel-clamp tool makes a tough job fairly easy when it comes to installing Adel clamps in the engine compartment. Several companies make these tools.

Miscellaneous Tools

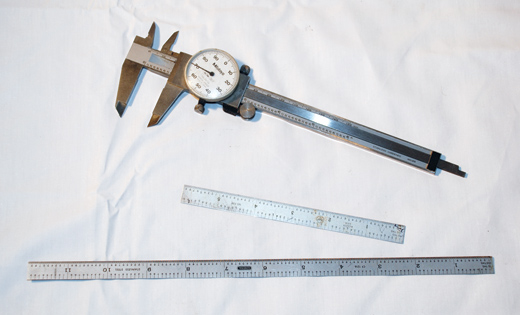

There are some special tools that really come in handy when installing an engine or building an airplane. The first are precision calipers. There are so many things you will want to measure that you will find such a tool indispensable. One with a 6-inch capacity and 0.001-inch graduations is about right for almost any precision measuring job. Machinist’s rulers in 6- and 18-inch lengths make a nice complement to the calipers.

Calipers and machinist’s rulers are useful throughout the building process.

A less obvious but no less useful tool is a hemostat. You don’t need the expensive ones that doctors use; the ones made for hobbyists will do. Allis forceps are also handy, and are similar to hemostats but with curved tongs instead of straight ones. They are useful for handling small parts such as washers and nuts, and for many other odd jobs.

Hemostats and Allis forceps (on the bottom) are handy little tools for hard-to-reach spots. The hobby versions of these are available for about $4 each.

Lastly, if your close vision is slipping a bit as the years roll by, a flip-down magnifier can be convenient. Sometimes those drugstore reading glasses just don’t get the job done. Machinist supply stores carry magnifiers.

A cordless Dremel tool with an assortment of cutters is a versatile tool for cutting, sanding or deburring.

The Dremel tool works well to cut off stainless-steel hoses and for deburring large holes in firewalls. Other cutters can make short work of trimming fiberglass cowls.

There are certainly many other tools you may get, or even need, depending on your project, but this should give you a pretty good start. Borrowing, lending and sharing can help keep the cost down when it comes to seldom-used tools; just be sure to return whatever you borrow in good condition. If you are the lender, make a note of who has your tools so that you can find them when you need them. It is great when an EAA chapter invests in some of the important but less-commonly-used tools, but they too need a good tracking system so that tools will be available to members when needed.

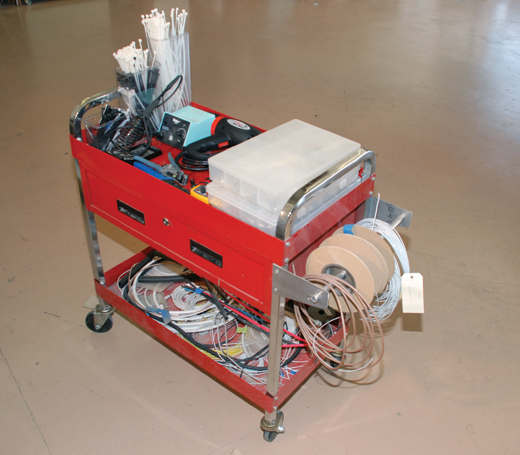

A dedicated tool cart for sheet-metal tools and rivets keeps everything together and portable, so that it can easily be moved to where the work is set up.

How to Get Organized

Organizing your tools so that you can easily find the right tool and tell when one is missing makes workshop life much easier. Some people like to hang tools on pegboard, but this can be limiting when wall space is at a premium, and it leaves everything out in the open for casual visitors to peruse. A good toolbox that is big enough to allow you to spread tools out might be a better choice. When it comes to specialized tools, a dedicated tool cart makes a lot of sense. These are available for a reasonable price at Harbor Freight. For example, a tool cart with all your sheet-metal tools can easily be moved to wherever you are working and provides a convenient place to collect similar tools that are otherwise not commonly used. Electrical tools, fiberglass tools and supplies, and fabric tools and supplies can also be organized easily with dedicated carts.

Here is a sample of the contents in a sheet-metal tool cart. Admittedly, this is more than you would need to do most firewall-forward installations.

- 2X and/or 3X rivet guns

- Pop-rivet tools

- Rivet sets, various sizes

- Bucking bars

- High-speed air drill

- Clecoes, various sizes

- Cleco pliers

- Riveting frame

- #40 and #30 drill bits, standard and extra-long lengths

- Trays of various sizes and types of rivets

- C-type pneumatic rivet squeezer

- Hand rivet squeezers

- Hand seamer

- Sheet-metal sheers—right, left and straight

- Deburring tools

Here is a sample of what might go in an electrical tool cart:

- Multimeter

- Wire strippers

- Ratcheting wire crimpers, 22 gauge to 10 gauge

- Ratcheting crimper for coaxial cable

- Heavy-duty crimper for large wire, #8 to #0

- Wire cutters

- Heat gun

- Heat-shrink tubing

- Soldering iron and solder

- Assortment of various wire ends, Molex connectors, etc.

- Rolls of common wire sizes

Nothing in these examples is meant to suggest that you need to be this elaborate simply to install an engine. But if you are just beginning to build, or if you expect to work on another airplane project in the future, this sort of arrangement may make sense.

With an engine and prop selected, and with tools in hand, we will begin the actual engine installation process in the next article, starting with the firewall. From there, we will look at each system until we have a complete firewall-forward installation ready to run.

An electrical cart can work well to group tools, wire ends and wire together in one convenient spot, and it’s mobile. Harbor Freight usually has carts for a good price.