Many of us who were around in the 1970s will remember the little Rand Robinson Engineering KR-2. It was the more common, two-place development of Ken Rand’s high-efficiency, single-place KR-1 sports plane. An early foray into foam and fiberglass-constructed airplanes that preceded even the nowadays more common VariEze, the KR-2 was claimed to be quick and easy to build, and fun and fast to fly.

Owner Allen Buzza spent 14 years building his KR-2.

Rand was a professional flight-test engineer with the Douglas Aircraft Company, who had previously been a keen pylon-racing model maker, so he clearly knew his business. He introduced a similar modeling style—low cost and quickbuild techniques—to amateur aircraft construction, claiming that his airplane would be easy for the new builder and would require a minimum of workspace, tools and skills. It was designed around standard size materials; for instance, the fuselage uses exactly five standard sheets of 4×4-foot plywood.

This was an Experimental homebuilt, so a certified aero engine was not needed. The humble and inexpensive Volkswagen Beetle engine would be more than good enough to power the lightweight, low-drag airframe. Not surprisingly, KR-2s soon became popular. Thousands of sets of plans were sold worldwide, and hundreds of examples were flying by the end of the decade.

The KR-2’s efficiency and low operating cost come not only from its wood frame, fiberglass skinned, lightweight construction, but also from the frugal air-cooled VW engine. Few other two-place types can fly behind this powerplant, and few if any VW-powered airplanes can go so quickly.

Construction is a simple wood framework with foam formers and

Rand claimed a maximum cruise of 180 mph at sea level, though, like all such claims, this might be somewhat exaggerated. However, the KR-2 does have comparatively impressive cruise performance with low fuel consumption. It achieves this by being extremely light, with a very low wetted area, which in turn means it is short and compact.

Structural Matters

The KR-2 has a simple wood framework, with foam formers and a fiberglass skin. Its fuselage is basically a wood box (known to Rand aficionados as “the boat”) with a flat bottom, tapering sides and a turtledeck of glass-skinned foam. The removable wings have twin built-up spruce spars and foam ribs, as do the empennage and control surfaces.

Many builders spend months filling and sanding the glass to remove undulations and even the tiniest of corrugations. This usually results in a beautifully smooth finish, but it does add weight, sometimes a lot of it, depending on the type of filler. As a result, the less pretty but lighter examples often fly better than the pristine but overweight ones.

Aficionados call the wood box used for the KR-2’s fuselage “the boat.”

The KR-2’s outer wing panels detach, leaving a short center section (out to just past the maingear legs) integral with the fuselage. The wing bolts and attach plates can be problem areas, and the originally specified bolts were not truly big enough, so it pays to be careful here.

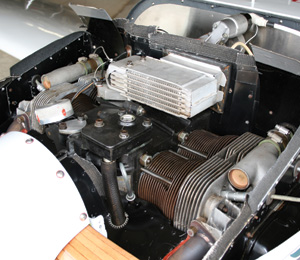

Cables operate all controls, which are also foam and glass sandwiches, and quite big for the small airframe. Volkswagens from 1835cc upwards can be fitted. This example has a 2074cc Aeropower VW conversion, using a single magneto directly driven off the crankshaft’s rear end, with dual spark plugs and a secondary ignition system using a Hall-effect trigger in what was originally the dynamo hole.

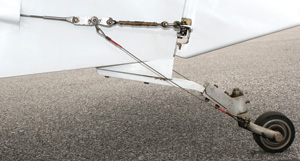

The Rand’s maingear legs are mounted on a transverse lateral beam, with suspension provided by torsion in the beam, giving perhaps 4 inches of travel. If either wheel rises too far (for instance from fast taxiing or landing heavily on rough ground), it can hit and damage the underside of the wing’s top skin, so it is usually preferable to fly a KR-2 off a hard runway rather than from gravel or grass.

All controls are cable activated.

Being amateur built, all KR-2s will be a little different from each other. Most will have a higher canopy than the one I flew, so their forward visibility would be better (possibly much better). The original KR-2 was basic, short and light. For comparison, the single-place Turbulent, Taylor Monoplane and Corby Starlet are all higher and longer, and only the Starlet has a smaller span.

Rand was not a big guy, and it is often difficult to complete the airframe within the prototype’s claimed 440 pounds, so though some KR-2s are true two-place airplanes, most (like this example) should be considered a roomy single-place plane that can be flown occasionally and over short ranges with two occupants. This one is typical, and weighs 632 pounds empty. Nevertheless, a few years ago, one British couple did fly their KR-2 the 12,000 miles all the way from England to Australia, a truly impressive undertaking!

A 2074cc VW engine is more than up to the task of powering the lightweight KR-2.

A subsequent development was the KR-2S with a 16-inch fuselage extension, 2.5 feet more wingspan and a new, 3 inch higher canopy, all of which must make a huge improvement in runway performance, forward visibility and handling, along with increasing the weight and probably reducing top speed a little.

Some later examples have a wider cockpit and/or additional wing tanks, and there are a few with fixed and/or nosewheel landing gear. Longer span horizontal stabilizers, and vertical and horizontal stabilizers with more area are available, all of which should improve its pitch and yaw stabilities while usefully allowing a wider center-of-gravity range. New airfoils have also been developed, claiming 10 knots more top speed, better climb performance and improved low-speed handling.

The VW engine purrs thanks to a full-width muffler under the cowl.

Mount Up

To sample the KR-2, you step up a mere 6 inches onto the small wing walkway, then down into the cockpit. Grip both fuselage sides to take your weight, and then carefully slide your legs forward under the instrument panel, ensuring you don’t skin your shins or inadvertently snag the landing gear downlock cables just ahead of the mainspar. Strap in, and pull on the slim cable behind your head to lift and close the canopy.

Headroom and knee room were just adequate for this six-footer. At 37 inches wide, this cockpit would be very snug with two men in it, but full control throw is still easy on both of the short control columns, and the stick forces are light. Combined with those relatively big control surfaces and the airframe’s ultra light weight, this suggests snappy handling.

A short step onto the wingwalk sets you up for entry into the cockpit.

Step on the toebrakes, turn on the master switch, open the fuel shutoff valve, pull out the choke knob, pump the throttle plunger twice and crack it a quarter-inch. Turn on both ignition systems, select “Start” and the diminutive propeller spins into life with a most unVW-like purr thanks to a full-width muffler under the cowlings. Check the oil pressure, release the brakes and you’re slowly, gently away.

There are no springs in the tailwheel steering linkage, making it direct and excellent, with a nice, tight turn radius at full pedal travel, but super fine precision at small deflections. The go-kart brakes are OK, but owner/builder Allen Buzza warned that they wouldn’t hold the airplane against more than 2000 rpm, and I’d already noticed that they judder a bit. For low-speed maneuvering they’re fine.

The narrow cockpit would be snug with two people onboard, but you could still move the control its entire throw on each side.

A fixed-pitch wood prop is the way to go.

Thanks to a non-standard, super sleek Lancair canopy and my rearward seating position, the forward visibility was not very good to the right, and ahead it was just acceptable, though it was fine to the left. I’d have to rely to some extent on peripheral vision while the tail was down on the runway. I optimized my seating position with conformal foam cushions, so this was the best I could do, with my head hard up against that tapered canopy, leaning slightly inboard.

The engine runup was straightforward, and the electronic ignition was indistinguishable from the magneto, with similar rpm drops. With no flaps or electric fuel pump to worry about, pre-departure checks were minimal, but given the airplane’s history of a canopy come undone in flight (it happened once to Buzza on takeoff), I was careful about checking its dual bolts, double hinge latches and mechanical secondary lock. Buzza suggested I first try a few high-speed runs to get the feel of the short-coupled airplane. [We do not recommend high-speed taxi tests prior to first flight in any homebuilt; we’re talking about something quite different here. —Ed.]

Buzza chose to keep the instrument panel relatively simple.

Prepared for Takeoff

Lining up carefully, I opened the throttle slowly, but I needn’t have worried. Acceleration was surprisingly quick, and directional control was no problem, with light left pedal pressure needed to straddle the centerline. Within seconds I was able to raise the tail, immediately revealing a brilliant view of the runway speeding by inches below my rear, and with no inclination to wander.

Then I gently closed the throttle, and understood Buzza’s caution. The tail dropped almost immediately, and I overcorrected for the tiniest tendency to veer right, promptly finding myself working the pedals to stay within reach of the centerline. After a couple more high-speed runs on the longest available runway I quickly got the hang of it, and returned to discuss things with Buzza before attempting flight.

Buzza does some preflight prep.

That’s when I discovered that despite its wing’s trusty and conservative RAF 48 airfoil and stout 18% thickness chord ratio, the KR-2’s very shortness gives it a restricted CG (center of gravity) range. I am taller and heavier than Buzza, so he had to remove his normal seat and cushions to improve my legroom. The result was that my increased weight was further aft than his, so for my high-speed runs the airplane had been close to its aft CG limit, if not slightly beyond it. For this reason, Buzza has two removable 2-pound ballast weights attached to the sternpost. Undoing these and topping off the fuel tank to 9 gallons moved the CG forward into the safe range, and I could go fly.

This time I had no difficulty straddling the centerline. The tail rose gently as speed increased, and after around 900 feet I was airborne at 45 knots and accelerating nicely. I could have retracted the wheels straight away, but elected to raise the nose, peg the airspeed at 70 and climb to 500 feet before attempting any internal gymnastics or external aerobatics.

The KR-2 accelerates quickly, with a bit of left rudder needed to keep it on centerline.

The landing-gear mechanism is in the cockpit’s center, to the right of your inboard knee on the mainspar’s forward face. First, you pull on the upper toggle to withdraw the locking pins via cables, though Buzza suggested it would be easier to press down on the mechanism’s upper knuckle. This allows the gear’s transverse beam to swing to the halfway position under air loads. Then you push the lower toggle forward until the whole visible mechanism rotates through 90°. There was a satisfying double click as the pins popped into the up-locks, easily checked; I sensed the acceleration as, relieved of nearly half its drag, the airplane surged upward.

Performance Figures

Both the VSI and my stopwatch measured 800 feet per minute, which is pretty good under mere Beetle power, particularly on a red-hot 35° C (95° F) day! The controls were light and effective, and I needed just slight left rudder pressure to keep in balance. (VWs rotate opposite to Lycomings and Continentals). Reaching 3500 feet, I let the airplane accelerate, and then retarded the throttle to 3200 rpm, at which it steadied at 120 knots indicated. That was 144 knots true airspeed (KTAS). Not bad!

Rand claims a climb rate of 1200 feet per minute.

Increasing to 3300 rpm gave 125 knots indicated, while a gentle 2800 rpm still returned a steady 95 knots. These numbers are extremely good when you consider that the 2-liter VW burns less than 3 gallons per hour.

As you might expect, this short-coupled design was only just stable in pitch, but as befits a professionally designed aircraft, it was positively stable, even under full power in the climb, which is usually the worst case. It was also surprisingly stable in yaw, considering its short fuselage. Unfortunately, we must have removed too much tail ballast, because I had to slide the trim lever fully rearward after takeoff, and a small residual pull force was still needed in all flight phases, so it was difficult to precisely establish roll stability. But I would say it was probably neutral.

I was pleasantly surprised at the Rand’s handling, which was much better than expected. It is a lively, responsive, point-and-shoot airplane, with nice, crisp controls and a good, fighter-sharp roll rate, but not at all twitchy. Control forces were light in all three axes, and it needed a mere breath on the rudder to coordinate turns. Its handling was generally exemplary.

So were its low-speed manners. Completely closing the throttle caused a slight pitch-down, and the speed was slow to decay, but it gradually unwound through 60, 50 and 40 knots, at which point a slight trembling buffet started in the airframe. Finally, at 38 knots, the stall warning sounded, and at 37 the nose gently nodded away. Holding the stick back against the stop merely caused it to rock and wobble, still in light buffet, but there was never any untoward behavior. Buzza had warned of a left wing drop, but when the ball was centered, I experienced none.

The lack of springs in the tailwheel steering linkage makes for precision maneuvering with small deflections. A trigear version of the KR-2 is also available.

Even at just 45 knots indicated, though it felt mushy, there was still good control in all axes, while setting 1800 rpm depressed the stall speed to 35 knots. Looking out at the tiny wings, I was amazed at the Rand’s good manners. But a glance at the vertical-speed indicator (VSI) revealed a trap. The needle was pointing well down past 1000 feet per minute! Now I knew why Buzza used a higher than expected approach speed.

Time to Land

With that sink rate in mind, I thought it would be prudent to fly a couple of practice approaches and go-arounds at altitude, carefully observing the VSI. In fact, I found no problems, and everything went well at Buzza’s recommended speeds, even during prolonged sideslips and slipping turns at 55 knots, though full rudder did cause some airframe buffet.

The maingear legs allow little travel, so it pays to be mindful of runway surfaces.

I even practiced cycling the gear a couple of times. The only factor of note was a slightly increased requirement for stick backpressure when the wheels were extended (as you would expect from their position). This made it a little more difficult to accurately hold the airspeed back, but of course that was preferable to the speed decaying if I was distracted.

Back in the traffic pattern, I followed Buzza’s advice, reducing airspeed early to enter downwind at 80 knots. Easing further back on the stick to decelerate to 75, and reaching forward to my right, I pulled first on the upper gear toggle and then on the lower one to extend the wheels. At this speed it wasn’t difficult, and Buzza has extended them in an emergency at over 100 knots, though he says the pull force becomes higher with increased speed.

Flying a curved base leg at 70 knots with 1600 to 1800 rpm gave me the best visibility of the runway. Reducing speed on final to 60 raised the nose, deteriorating my view, but I could still see well enough for accurate positioning. A little right rudder slip helped considerably, but it did further increase the need for back pressure.

Slowing to 55 knots as I crossed the fence, I tilted my head back to raise my eyes right up to the canopy for the best possible view. Unfortunately, that had me peering though the magnifying part of my bifocal sunglasses, so I had no alternative but to open the throttle and go around. There was no sink, but the Rand did take a couple of seconds to accelerate to 70 knots, after which the maneuver was routine.

Everything was simpler without the sunglasses, and a slight flare led to a positive three-point touchdown after I gently pushed off the drift. As Buzza had advised, I simply let it roll, concentrating on steering while holding the stick fully back. Slowing to a walking pace within perhaps 1500 feet without any braking, I finally squeezed gently on the brakes at around 20 knots and turned off the runway.

This was not the easiest airplane I’ve ever flown, but it was far from the most difficult, and it was tremendous fun. A higher canopy would have made it much less demanding, but you will be hard-pressed to find a sleeker or faster two-place airplane on Volkswagen power.

Complete airframe kits, subkits and plans are available from nVAero, 800/515-4811, www.nvaero.com. There is a Rand builders’ forum at www.krnet.org.

Like the popular Volkswagen slogan used to recommend: Think small.

A note to Steve

Are you sticking with the original KR2 design or upgrading your kits to KR2s? Obviously the KR2s longer fuselage should be more user friendly and cost difference should be minimal. Also now with availability of more powerful engines has the wingspan been increased?

Id be keen to see more details about your fastbuild fuselage kits (composite or timber?)