Selecting a GPS for your project has never been easy, even in the early days of TSO C129(A1) GPS technology. This regulatory spec was for earlier-gen IFR GPS en route and non-precision approach-approved navigators that ushered in the age of instrument approaches by GPS. While we’ve never looked back (and while we weren’t looking the competition thinned out), the buying decision is no easier today with the current lot of precision approach-approved WAAS models from Avidyne and Garmin.

There’s good reason to upgrade or equip your new kit with the latest box. Today’s current-production navigators carry TSO C146C certification for primary GPS en route, terminal and approach ops, enabling you to fly a GPS-guided LPV flight path to ILS-comparable 200-foot and ½-mile approach minimums. They also have integrated VHF com radios and VHF nav receivers, although Garmin offers some new choices that don’t include com and nav (suggesting a new trend), and there’s one model that even includes an integrated ADS-B transponder.

There’s good reason to upgrade or equip your new kit with the latest box. Today’s current-production navigators carry TSO C146C certification for primary GPS en route, terminal and approach ops, enabling you to fly a GPS-guided LPV flight path to ILS-comparable 200-foot and ½-mile approach minimums. They also have integrated VHF com radios and VHF nav receivers, although Garmin offers some new choices that don’t include com and nav (suggesting a new trend), and there’s one model that even includes an integrated ADS-B transponder.

Over at Avidyne, the company’s IFD series is designed to slide into an existing Garmin GNS 430W or GNS 530W installation for a modern refresh without major rewiring or metal work. If you aren’t sold on a touchscreen interface, Avidyne has you in its sights.

In this buyer’s guide article we’ll offer a bird’s-eye view of what to expect when shopping for a new IFR navigator. It’s impossible to dive deeply into the feature set in a roundup like this—they all do far too much, and you should get a hands-on demo before you buy—but we’ll look at compatibility and major features that make one stand out over another. Let’s start with Avidyne.

Avidyne IFD Series

The company’s IFD navigators initially got off to a slow start after getting snagged in certification, but Avidyne has earned considerable industry respect by giving Garmin some competition with a seriously capable alternative. Moreover, Avidyne has incrementally advanced the IFD interface by adding clever features and utility (usually through field-updatable software), while being mindful of third-party compatibility.

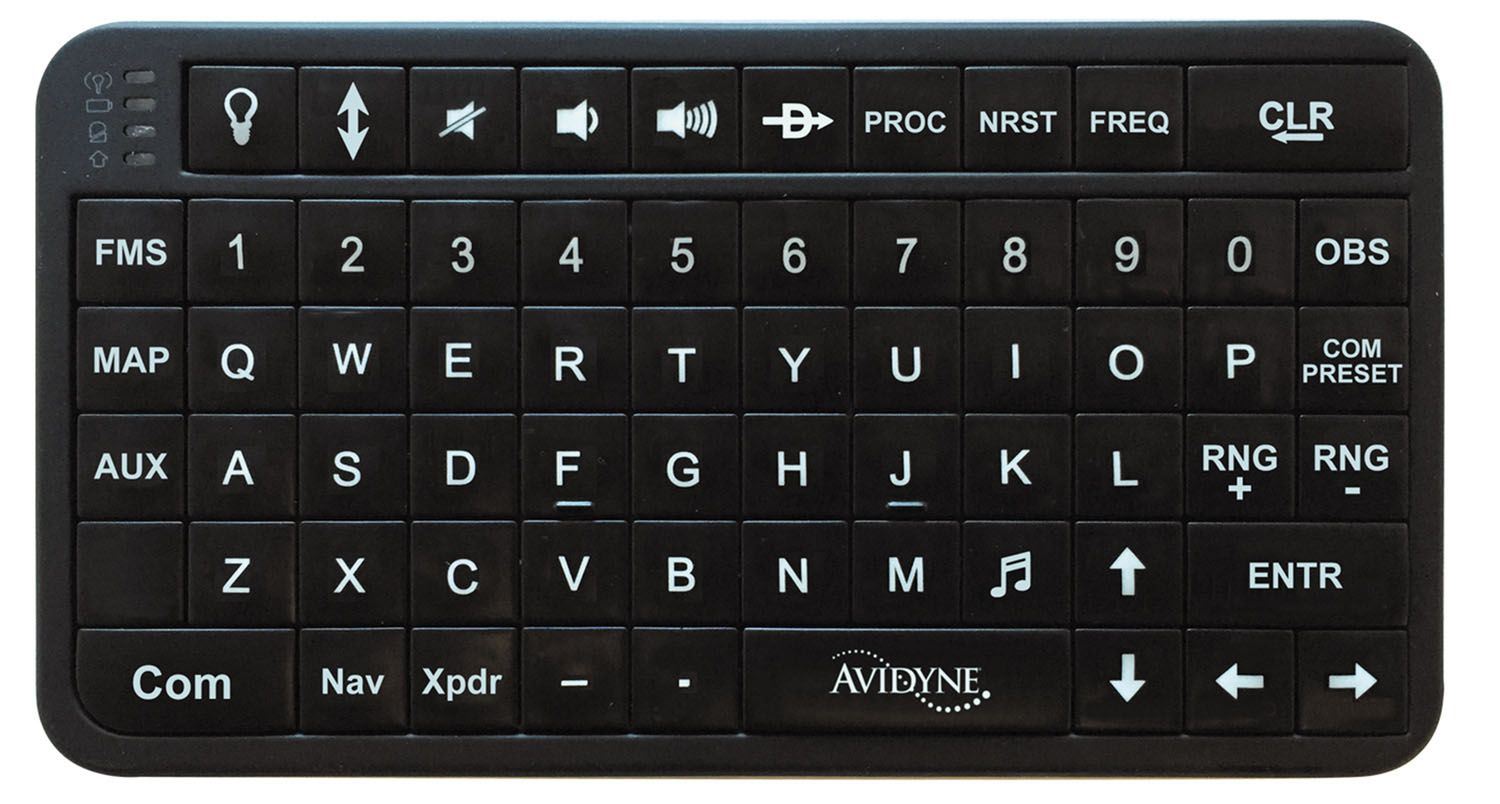

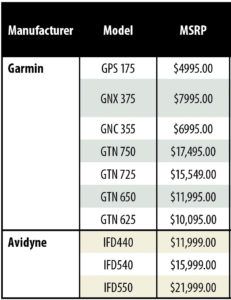

The IFD series, which includes the entry-level $11,999 IFD440, the $15,999 IFD540 and flagship $21,999 IFD550, still attracts buyers that aren’t sold on a total touchscreen interface. Early on (and still today), Avidyne pitched the IFD as a hybrid system, using a combination of bezel controls and touchscreen. Anything you do with touch you can also do with hard controls. Inevitably, most users use a combination of both for typical data input and overall box interaction. There’s also an external Bluetooth QWERTY keyboard for controlling the box in your lap, on the yoke or wherever you’d like to stick it. Count ’em up and that’s a handful of ways to operate these navigators, depending on what suits the user. And when you consider just how deep the feature set is on a current navigator, it sure is nice to have choices.

There’s also built-in Wi-Fi, which is used to interact with Avidyne’s IFD100 iPad app, offering another screen to mirror the data that’s on the navigator—helpful if you decide to go with the base IFD440. There’s also compatibility with ForeFlight and other apps. Avidyne believes in open architecture, and it’s evident in the IFD series.

The other draw is that the line was originally designed to replace existing Garmin GNS 430W (with the smaller IFD440) and GNS 530W (with the IFD540/550) navigators with minimal rewiring, although there might be some if you want the audio alerts that are useful during some approach segments. Nearly every external system that connects with a Garmin navigator will also work with the Avidyne. Traffic sensors, sferics systems, weather receivers (including the Garmin GDL 69/A SiriusXM unit), navigation indicators—including Garmin’s GI-106 series, plus EFIS displays and mechanical HSIs—can work with the Avidyne without repinning the connectors. The existing Garmin GPS antenna will even work as long as it’s a WAAS antenna because the IFD was intended to replace GNS WAAS units, not non-WAAS legacy GNS 430 and GNS 530 boxes.

In its latest version R10.2.3.1 software release, Avidyne added compatibility with the hugely popular Garmin G3X Touch. Additionally, the IFD units work with Dynon’s SkyView displays (they work with plenty of others, too) and have full autopilot capability.

IFD440, 540 or 550? Size Matters.

Like the headline said, the first step is to decide what size navigator you want—and between manufacturers there are lots of choices. As for sizing up Avidyne’s IFD440, think same size as the Garmin GNS 430W, because that’s what it replaces, while the IFD540 and 550 are sized to replace the GNS 530W.

The IFD440 stands 2.66 inches high, and the screen is 4.8 inches diagonally. With mounting hardware it weighs 6.6 pounds. As with all the Avidyne navigators, synthetic vision is standard. So is the 10-watt com radio and VHF nav receiver, including glideslope.

If there’s a single reason to upgrade from a GNS 530W to the IFD540/550, it might be to gain a superior VGA-quality display. The IFD540/550 display measures 5.7 inches diagonally on a touch LCD of 65,535 colors in 640×480 pixels. Check that against the stark GNS 530 series—it was designed with a 5-inch diagonal, eight-color 320×234 TFT LCD. Yeah, so 1990s. For those looking for more advanced FMS functions, Avidyne has a full-featured FMS built in. It carried over a feature that’s been a big hit with the FMS system in the company’s R9 integrated avionics suite. It’s called GeoFill. When entering and editing waypoints, GeoFill accurately guesses the next waypoint in a flight plan after only one or two characters are entered. The system is smart enough to know what waypoint you’re looking for based on position, curtailing the data-entry process. Yes, Garmin has a similar utility in its navigators, as you’d expect.

What differentiates the flagship IFD550 from the IFD540 is the IFD550’s ARS, or attitude reference system. Other than accepting a heading input from Aspen’s Evolution PFD, in addition to Garmin’s G500/600 PFD and select air data computers, the Avidyne ARS is self-contained. The navigator also sends GPS nav and course data into the displays over an ARINC 429 data stream. For dual installations (maybe an IFD550 and IFD440), the connections are independent for redundancy, but have full synchronization.

The IFD550 has an internal attitude reference sensor or ARS, displaying pitch and roll data directly on the screen. The IFD550 won’t display airspeed or altitude (just pitch, roll and slip/skid data), although when the navigator is connected to an air data computer (including the Aspen or Garmin PFD), airspeed and altitude data passes through the IFD550 and is sent via Wi-Fi for display on the IFD100 tablet app. If the IFD550 is receiving heading input from an approved source, there’s onscreen heading and rate of turn.

The IFD550’s SynVis function (overlaid directly on the IFD display) uses GPS-based MSL altitude and a 9-arc per-second terrain database to display a 3D egocentric out-the-window view. There’s a total velocity vector/flight path marker that indicates where the aircraft is going, plus the yellow triangular aircraft reference symbol that indicates where the aircraft is pointing. The display also shows airport flags, 3D traffic, terrain and obstacles, plus large bodies of water. If you used synthetic vision on a PFD or on a tablet, your eyeballs will be at home on the IFD.

Worth mentioning is that in addition to attitude data, the IFD550 displays lateral and vertical approach guidance directly on its screen. This means if the primary flight display screen fails, you can still fly the approach by referencing the lateral and vertical guidance on the IFD550 screen. It might not make for the most efficient scan, but it’s better than the alternative.

ADS-B Compatible

As we’d expect, the IFD navigators are an approved WAAS position source for connecting to ADS-B Out equipment. So if you have a 1090ES ADS-B transponder that doesn’t have built-in WAAS, you can use an IFD as the position source to meet the January 2020 ADS-B Out mandate. Avidyne sells a couple of ADS-B transponders of its own, plus audio panels if you want to buy all Avidyne.

For ADS-B In, the navigators display ADS-B weather and traffic data from the L3 Lynx, the GTX 345 and from Avidyne’s Skytrax 100. The Garmin GDL 69-series SXM receiver is also compatible.

We like the Avidyne 3D traffic feature when the boxes are connected to an ADS-B In or TAS receiver. In a nutshell, the system’s SynVis function depicts targets using the same symbology as it does in the navigator’s thumbnail traffic view. However, the SynVis presentation helps to identify the relative threat of the traffic by altering the size of the onscreen target. In other words, as the traffic target draws nearer to your own position, it grows in size in the SynVis scene. To reduce screen clutter, targets outside of 10 nautical miles aren’t displayed unless they become a proximity or traffic alert.

BendixKing Rebranded

Last year BendixKing started selling Avidyne’s IFD navigators, and you’ll see them rebranded as the AeroNav 800 (IFD440), AeroNav900 (IFD540) and AeroNav910 (IFD550). Pricing is the same as the ones wearing the Avidyne colors.

Garmin’s GTN Series

When Garmin introduced the GTN 700- and 600-series navigators somewhere around 2012, buyers looked for substantial improvements over the dominant but aging GNS 530 and 430. Garmin stretched the GNS production run as long as it could, while its once competitor, BendixKing, slept at the controls and never added WAAS to its capable KLN 94 color navigator. It took years to certify the KSN 770 navigator and never expanded the feature set—even to the point of making it fully ADS-B compatible. The KSN 770 is history. Garmin rolled right along, however, and added WAAS to the GNS, of course, but the wish list for the second-generation, all-in-one navigators included a more modern display and integrated charting—including the cherished airways feature. And it also needed a better display and an easier way to update the database. Owners were growing tired of dealing with time-consuming updates and having to use Jeppesen’s Skybound reader data card adapter (which was unique to the GNS).

Moreover, the GNS lacked the horsepower and display resolution (and colors) that pilots learned to expect after bringing tablets to the cockpit. The iPad really showed the GNS 530 and 430 how it should be done. Skeptically, the market expected a touchscreen feature set. Garmin delivered all of the above, of course, and it’s tough to argue that the $17,995 GTN 750 and smaller $11,995 GTN 650 haven’t been a success.

But we also think Avidyne has stolen a good amount of sales from Garmin with its slide-in IFD navigators. For many, that swap-out can be accomplished in a few hours. But no, the GTN won’t slide in to a GNS install—it’s a total rewire job.

If your eyeballs are accustomed to the old GNS navigators, the GTN will seem like worlds ahead, and it is thanks to screens with a big pixel count. On the 650, it’s 600 by 266 pixels while the 750’s 6.9-inch touchscreen has 600 by 708 pixels. That’s about a five-fold increase in pixel density over the GNS. Both screens have 250,000-plus colors—just what you need for weather, terrain, charting and topo data. There’s no synthetic vision in these navigators, but they support Garmin’s 9-arc per-second terrain mapping capability.

To get all that screen area, Garmin essentially shrunk the bezels down to the bare minimum by stripping the keys and reverting to a touchscreen. The GTN 750’s chassis stands 6 inches high in the panel and the GTN 650 is 2.65 inches. Other than a Home key and rotary knobs, the feature set is all touch. To this day some love it, some hate it, and some put up with it. But touch is here to stay, and if you can’t deal with it, there’s always Avidyne’s hybrid approach.

And yes, we all know that a touchscreen can be a nightmare for ham-fisted pilots in the bumps, and the navigators have channels along the bezel to steady your fingers. They work, mostly, but our advice it to know the feature set cold so there’s minimum time hunting the menu structure for what you’re trying to accomplish while getting your butt handed to you in the bumps.

Flight Stream 510 Wireless

The GTN navigators have Bluetooth and Wi-Fi through Garmin’s clever Flight Stream datacard. Part of the Connext cockpit wireless platform, the Flight Stream 510 is an MMC datacard that contains both Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connectivity capability. Worth noting is that the first-gen Flight Stream—a hard-wired remote box—only has Bluetooth. The new Flight Stream works by removing the database card that lives in the slot of a GTN750/650 series navigator (which requires a field software update) and sliding the Flight Stream 510 card in its place. Powered by the navigator, the Flight Stream 510 becomes an integral part of communicating with Garmin’s Pilot tablet app for iOS and Android.

Garmin makes use of the Flight Stream’s Wi-Fi capability for enabling its database concierge function—something we applaud because it’s so much better than the GNS database chore. With the new Flight Stream, the process is streamlined—and the data transfer speed is increased substantially. Select and download the appropriate databases directly on Garmin’s Pilot app, where the data is stored for use once you get to the aircraft. Once the Flight Stream 510 establishes a Wi-Fi connection with the tablet, the data is automatically transferred to the navigator. You can transfer databases ahead of time (helpful if you are launching on a trip on the heels of a new database cycle), since the data waits in standby mode until it becomes the effective data. If you don’t want to fetch the data with Garmin Pilot, the Flight Stream MMC card can be inserted into a USB slot (using a provided USB card reader) in a computer for direct download.

Even better is that Garmin has figured out a way to synchronize the databases among multiple boxes. No more separately loading databases in each unit. Think of a Flight Stream 510-equipped GTN navigator as a server. When it’s wired to a second GTN and/or to a Garmin PFD, it automatically transfers the data to the connected systems.

Standard charting includes Garmin’s FliteCharts (Jeppesen charts are optional) and also SafeTaxi airport diagrams. It’s a complete data package as standard.

The Flight Stream 510 is compatible with the GTX 345 and GTX 345R ADS-B transponders, plus the GDL 88 ADS-B transceiver. Since ADS-B traffic and weather from these systems are interfaced with a GTN navigator, the data is transmitted via Bluetooth into the Garmin Pilot or ForeFlight Mobile tablet apps. The stream also includes GPS position. Flight Stream also works with the GDL 69 and GDL 69A SiriusXM datalink weather and entertainment system, allowing entertainment control directly in Garmin Pilot, plus the display of satellite broadcast weather.

Audio and Remote Transponder

To save more space in the panel, the GTN 750 works with the remote-mount GMA 35 audio panel, with onscreen audio control directly on the GTN 750’s display. This also paved the way for Garmin’s Telligence voice control feature, which enables you to activate key functions by using spoken commands. You’ll need to wire a dedicated key switch for speaking the commands. Key it up and speak “tune destination tower,” and the system automatically plucks the frequency from the database. That’s only one. The pilot’s guide lists over 100 recognized commands to choose from. Should the GMA 35 panel not recognize a spoken command, a negative acknowledgment tone will be played. When it understands the command, a positive acknowledgment chime is played. Some commands are acknowledged by a voice response from the audio panel. It’s pretty slick. The rear of the 750’s chassis has a shelf for mounting the remote audio panel, so it’s also a space saver.

The GTN 750 can also channel Garmin’s remote transponders, including the ADS-Out GTX series, displaying the squawk codes in a transponder window directly on the screen.

Nav Display

The GTN navigators have a rich ARINC 429, Ethernet and serial data interface, and as such they work with a wide variety of EFIS displays, plus old-school analog HSIs. But for traditional analog nav indicators, the boxes require an OBS course resolver interface. This is where the navigator listens for an output from the indicator confirming that the pilot dialed in the desired course for the active flight plan segment. In the real world, a resolverless interface means that when you put the navigator in OBS mode (maybe you want to draw an extended centerline off the runway for intercepting and tracking inbound), you’ll have to manually enter a course value in the navigator. But with an indicator that has resolver, you can crank that value in from the indicator’s OBS knob.

Indicators that have OBS course resolver include Garmin’s own GI-106A/B nav heads, most analog HSIs including the King KI 525 (part of the KCS 55A remote compass system), and BendixKing’s later-generation KI 209A. (It has to be the “A.” Plain-vanilla KI 209s don’t have OBS course resolver.) Since the interface is digital rather than analog, EFIS displays take care of the course resolution. Compatible displays include, but aren’t limited to, Garmin’s own EFIS, of course, including the G5 electronic HSI display, the G3X and G3X Touch, TXi series, Dynon SkyView and Aspen Evolution. We’ll look at EFIS compatibility in a dedicated EFIS buyer’s guide in an upcoming issue of KITPLANES®.

Garmin’s Budget Navigators

In addition to Garmin’s flagship GTN 750 and GTN 650, which have been in the company’s product line for a number of years (we’ll recap them in a bit), it recently introduced three new navigators catering to lower budgets and also to panels that may be tight on real estate. We recently covered these new units in the August 2019 issue, so we’ll summarize the line here, which now includes a new addition: the com-equipped GNC 355.

The $4995 entry-level GPS 175 is strictly a GPS with 4.8-inch color touchscreen that stands 2 inches high in the panel. This is sized right for replacing vintage navigators with little panel work. We’re talking the King KLN 90/89, Apollo GX units and even Garmin’s long-retired GPS 155/GNC 300.

If you want a com radio with that, the $6995 GNC 355 has a 10-watt transceiver. The $7995 GNX 375 has no com, but instead a mandate-compliant 1090ES ADS-B Out transponder. As you’ll see in Marc Cook’s sidebar on Page 38, it’s pretty convincing to see why the GNX 375 can be a good fit for so many panels, particularly those still needing ADS-B and transponder upgrades.

We need to stress that none of these units—all IFR navigators with WAAS—have VHF nav receivers. No VOR, no localizer and no glideslope. These are strictly GPS. Read our roundtable discussion on the topic of ditching the VHF nav in the December 2019 issue of KITPLANES®.

At first blush the new units sort of resemble the GTN 650, but as noted they are shorter. That means there is a lot of data crammed into a small screen. We like that Garmin includes visual approach guidance as standard in these new boxes (as they do in the GTN 650 and 750) and also the Flight Stream 510 wireless card. This means you can wirelessly connect them with an iPad running Garmin Pilot or ForeFlight, and with Garmin’s late-model portable GPS for flight plan transferring. With the GNX 375, you can output the ADS-B weather and traffic data, too. It’s the saving grace for the small screen, really.

These 4.8-inch small screens do fairly well in direct sunlight. The display resolution is 732 by 240 pixels, and of course, there’s pinch scaling and scrolling the map. Standard is Garmin’s SafeTaxi airport diagrams and Flight Charts.

We’re glad Garmin made the wise decision to include compatibility with a wide variety of third-party nav indicators. While they don’t have VHF nav receivers, you still need an external nav head to display GPS course information. But unlike the GTN series, the new units don’t require OBS course resolver, opening the interface to common indicators like the King KI 209/KI 206 and even vintage indicators from Narco and Collins. If your kit is equipped with aging KX 155 or Narco MK 12D nav/com radios, for instance, the GNC 355 can be an easy and modern replacement since it will wire into the existing indicator.

If your kit is tight on space behind the panel, the GPS 175 will help. It’s only 7 inches deep from the edge of the front bezel to the rear of the chassis. The GNX 375 and com-equipped GNC 355, however, are deeper at just shy of 11 inches.

Wrap It Up

We can’t stress enough that unless you have experience with Garmin’s latest GTN series and are happy with the way it works, you have to try these IFR navigators before buying one. That’s especially true when deciding to buy an Avidyne over a Garmin. That’s not saying either one will be a bad choice, but you have to pick an operating logic that suits you best. There will be a huge learning curve with whatever you select. Plus, try using a Garmin keystroke logic when programming an Avidyne and you’ll fail. They’re just different.

If we had to pick one of these systems for the aircraft that needs a modern navigator, mandate-compliant ADS-B and a transponder upgrade, we’d pick the Garmin GNX 375. We’ll give it a big ding for not having a com radio. Garmin said it couldn’t fit both the transponder and com in the chassis. Want to get out of an aging GNS and don’t want to rewire? It’s a no-brainer to consider an Avidyne, and you could also get a healthy trade-in allowance.

But in the end there’s no arguing that you have choices in all price points. There are plenty of IFR navigators to choose from, and we think all of them are loaded with useful features for a combination of IFR and VFR flying. So decide if you need VHF nav, measure your panel, set a budget and go find one of these things to try (and fly) before you buy.

Being a daytime – VFR only Light Sport pilot, this article reinforces my choice!