Brakes are pretty simple to install and maintain, but they are also pretty important. The stopping, and in many cases steering, of your airplane depends on good brakes, so it is no place to cut corners or ignore needed maintenance.

Once you get your airplane built and flying, it will only be a matter of time before your brakes wear out. When they do it is easy enough to install new brake pads, but you will need a special tool or two to do it. Fortunately, the tools you will need are not very expensive or difficult to use, and the process is simple if you just take the time to learn some basic techniques.

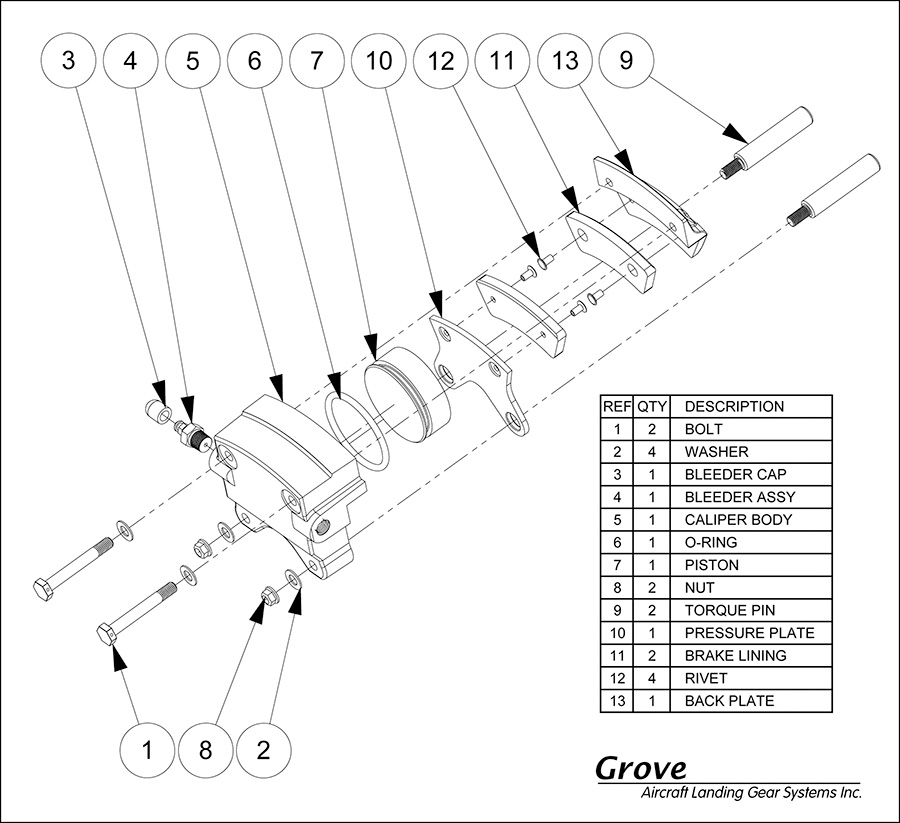

A review of the basic parts and operation of the brake system at the wheels is in order. Hydraulic fluid is pumped by the master cylinder at each rudder pedal (or heel brake pedal) into the caliper. Once the fluid enters the caliper, it forces a piston to put pressure on the press (or pressure) plate, which squeezes the brake pad against the rotor. The other side of the rotor is squeezed by the pad attached to the back plate, thus applying pressure to both sides of the rotor and slowing the aircraft down.

Step-by-Step Brake Pad Replacement

Here are the basic steps to replace your brake pads if you have Cleveland or Grove wheels and brakes with non-metallic pads:

1. Remove your wheelpants if present.

2. Unbolt each caliper by removing the two bolts that hold the back plate to the caliper body. (You should have to snip some safety wire to remove these. If not, someone forgot the safety wire last time.)

After removing the wheel pants, the first step is to remove the bolts that hold the back plate to the caliper body.

3. Once the caliper is unbolted, the caliper body with the hydraulic line attached to it should slide off its torque pins (Cleveland calls these anchor pins) and allow you to also remove the press plate. If possible do not remove the caliper from the plane or disconnect the hydraulic line. If you must disconnect the hydraulic line to slide the caliper out far enough to remove the press plate, be sure to plug off the hydraulic lines to minimize the loss of brake fluid and possible contamination.

If you must remove the caliper from the aircraft, be sure to plug off the brake lines to avoid contamination and fluid loss.

4. The brake pads are riveted to the back plate and the press plate. Measure the remaining brake pad thickness to verify that replacement is required. Useable pads should be at least 0.10 inches thick, with no protruding rivet heads and no cracks.

Measure the thickness of the brake pads to see if they need replacing. The minimum thickness is 0.10 inches.

5. Assuming you need to replace the pads, clean the parts thoroughly with brake cleaner and acquire some new brake pads. Be sure to wear eye protection when spraying brake cleaner.

It is much easier to remove the old rivets if you first drill off the tails. Be sure not to drill into the metal of the back plate or press plate.

6. To remove the old brake pads, you will want to drill out the shop heads of the rivets. The shop heads are the ones with the dimple in the middle, not the flat heads visible from the side with the brake pads. Carefully drill off the tails of the rivets without getting into the metal for the back plate or the press plate. A quarter-inch drill works fine for this.

The brake rivet tool is set up to push out the old rivets. This can also be done with a punch, but the tool does a much better job with less potential to damage the rivet holes.

7. Once the rivet tails have been removed, use a brake pad rivet tool to push out the old rivets. You can buy one of these tools from your favorite aviation vendor for around $15 or $20. A small drift punch will also work for this, but the brake tool includes a special pin to remove the rivets, so you might as well use it. The special tool is less likely to damage the rivet hole.

8. Once the rivets have been removed, inspect the rivet holes to be sure they have not been damaged by your efforts or previous work. If the rivet holes have been elongated or drilled oversized inadvertently, you will need to replace the damaged parts. It is OK to deburr the holes.

9. Clean the surfaces where the new brake pads will be secured and check to be sure the back plate and press plate surfaces are perfectly flat within .010 inch. Straighten them if you can, or replaced them if necessary.

10. Replace the rivet punch in your brake tool with the rivet squeezing parts.

Installing new rivets using the rivet tool. Masking tape holds one rivet in place while squeezing the other one. That way both rivets can be used to properly align the new brake pad.

11. Set the new pads in place and push in the new rivets. Tape one rivet so it won’t fall out while squeezing the other rivet. The two rivets keep the pad properly aligned while riveting.

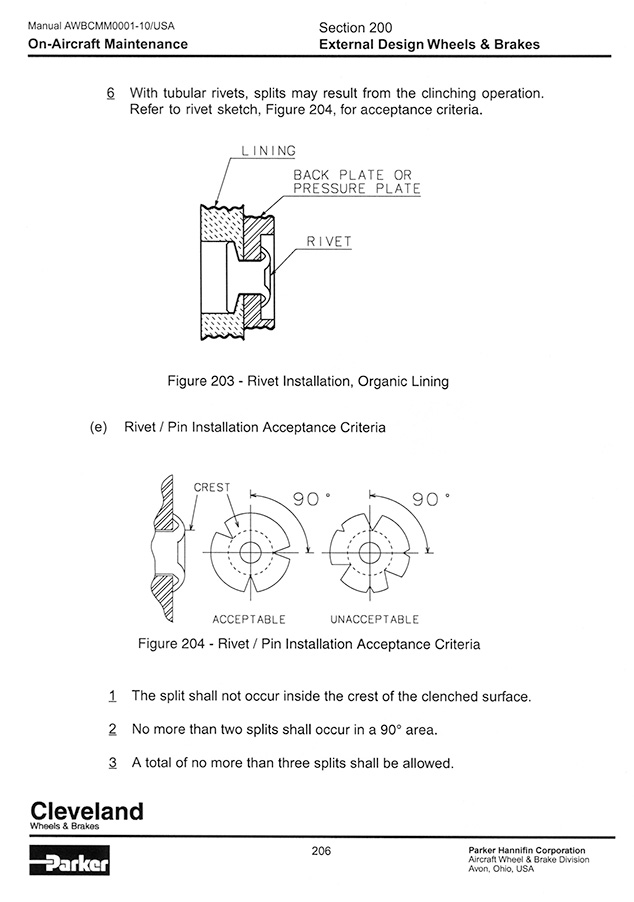

A page from the Cleveland maintenance manual showing the allowable splits in the shop heads of their brake rivets. Ideally your rivets will not have any splits in them at all.

12. Squeeze each rivet by tightening the tool until it bottoms out firmly. Excessive force is not required to properly squeeze the rivet. Too much squeezing pressure can lead to cracked brake pads and/or poorly formed shop heads on the rivets. Take it easy. If you crack a brake pad, it will have to be replaced. The shop heads of rivets are allowed up to three small cracks if they do not extend inward beyond the crest of the newly formed head and are at least 90 degrees apart, but properly installed rivets will seldom have any cracks. (For those metal airplane builders who have a hand or pneumatic squeezer, a set of special brake rivet dies are available that make perfect rivets every time.)

The press plate with a new brake pad installed is positioned on the torque pins prior to installing the caliper back on the aircraft. Be sure to lubricate the torque pins with silicone or another approved lubricant (not grease).

13. Somewhere along the line you should check the condition and thickness of the brake rotors. If they are scored or warped they will likely need to be replaced. Isolated scoring up to .030 inches deep is allowed. Grove and Cleveland also have minimum thicknesses for their rotors. Do not reuse rotors that fall below the minimum required thickness. This can lead to total brake failure if the piston is allowed to push too far out of the caliper in an attempt to squeeze a too-thin rotor. Check with the manufacturer of your brakes to find out what the minimum thickness is for your rotors.

Check the thickness of the rotor, along with its flatness and general condition. See manufacturer’s literature for minimum rotor thickness for your brake system.

14. With the new pads installed, it is time to clean up the caliper bodies and reinstall the brakes. Be sure to lubricate the torque pins and be careful to keep the new pads clean as you work. A dry, non-greasy lubricant such as silicone spray is best. LPS Force 842 is also a good choice, but use Lubriplate X-357 for amphibious applications.

15. Bolt the calipers back together and torque and safety wire the bolts. Note: some caliper bolts are not set up for safety wire.

16. Reinstall hydraulic lines if they have previously been disconnected, and bleed the brakes. In all cases check the fluid level in the reservoir to make sure it is still at an acceptable level. It may be necessary to add or remove a bit of brake fluid to get the level back where it needs to be.

17. When all of this is done, it is time to check the brakes and condition the new pads.

An exploded view of the parts of a Grove brake caliper assembly. The Cleveland assembly is very similar, although they use different names for some parts.

Bleeding the Brakes

Bleeding aircraft brakes is pretty simple, but there are some who try to make it more difficult than it needs to be. There is an idea that aircraft brakes can be bled the same way people used to bleed car brakes, by pumping fluid through the system with the brake pedal. Whether or not this is a good way to bleed car brakes, it is not a good way to bleed aircraft brakes. To bleed aircraft brakes, start at the bottom—the brake caliper—and work up. Do not attempt to bleed brakes by adding fluid at the top and pushing the air bubbles out through the calipers. It just doesn’t work. Connect a hose to each caliper, one at a time, open the bleeder screw and pump brake fluid up until bubbles stop coming up in the fluid reservoir. Do this for each caliper and then check the brakes for proper feel. Repeat as necessary until both brakes have a solid feel. Do not pump the brake pedals while bleeding the brakes. Brakes that feel spongy or that pump up with repeated applications still have air in the lines somewhere. Continue the bleeding process until all sponginess and/or pumping up disappear.

An inexpensive brake bleeder can be made from an oil can, some plastic hose, and a brake bleeder fitting. Aircraft Spruce and other vendors sell this fitting for under $30.

To do this you will need a way to pump fluid into the system. Aircraft Spruce and other aviation vendors sell brake bleeders starting at around $85, but you can make your own setup for less than half of that without much trouble. All you need is a brake bleeder fitting, an oil can and some plastic hose. You can actually do it without the fitting, but it is much harder to keep the hose attached to the bleeder without the fitting. By the way, be sure to only use aircraft brake fluid that meets the MIL-PRF-5606H specification. It is not that automotive brake fluid will not work, but aviation brake fluid is better suited to aviation applications, and everyone who works on airplanes expects aviation brake fluid to be used. Just as mixing different types of automotive brake fluid is unlikely to work well, mixing auto and airplane fluids will likely lead to seal trouble.

A pair of wheels and brakes from Grove as commonly found on Experimental/Amateur-Built airplanes. Note the torque plates that will attach to the axles of the airplane.

Conditioning New Pads

To complete your brake job, you will need to condition the new pads. Non-metallic brake pads, such as those that are commonly found on Experimental Amateur-Built aircraft, depend on a thin glaze on the pads to obtain maximum braking friction. Normal brake use maintains this glaze, but new pads need to be conditioned to create the glaze initially. Note: If you have metallic pads, you will need to refer to the manufacturer’s literature for the correct installation and conditioning procedures, which are different from those listed here.

After you have made sure that you have good basic brake function, heat up the new brake pads by dragging the brakes while taxiing for about 1500 feet at 1700 rpm. Apply enough brake force to maintain a speed of 5 to 10 mph. After doing this allow the brakes to cool for about 10 minutes. Then test the brakes by doing a full-power static run-up. If the brakes hold, the conditioning process is complete. If they do not, repeat the process until they do. When performing these tests with an airplane with conventional gear, take care to keep the tailwheel on the ground at all times.

If you find any leaks while inspecting and servicing your brakes, be sure to take care of them immediately. It is pretty easy to replace the seals for the brake pistons or replace a damaged fitting. Take the time to do the complete job well and you will likely never have any problems with your brakes. Aircraft brake systems are simple and reliable and ask only a little from you in return for the valuable service they provide. Take care of them and they will take care of you.

For more information visit www.groveaircraft.com or www.parker.com/cleveland.

Photos: Dave Prizio, Courtesy Grove Aircraft Landing Gear Systems, Inc.,

and Parker Hannifin Corp. (Cleveland Wheels & Brakes)