How often do you wander the flight line and see a classic aircraft with a propeller that just makes you stop and go “Wow!” I mean, the plane might often catch your eye, but I’m referring to the propeller by itself being something so unusual it makes you pause and take a closer look.

How often do you wander the flight line and see a classic aircraft with a propeller that just makes you stop and go “Wow!” I mean, the plane might often catch your eye, but I’m referring to the propeller by itself being something so unusual it makes you pause and take a closer look.

I remember seeing a single-blade counterweighted prop on a Cub for the first time and going, “Wait! We gotta go check that out!” Or one that is an absolute work of art. You know the type I’m referring to: one with smooth, glossy, dynamic, silky layers of wood that seem to curve and scythe through the air even when standing still.

At this year’s annual Pietenpol Reunion in Brodhead, Wisconsin, among the rows of Piets, Dan Helsper’s airplane stood nose and prop blades out from the others. Its light caramel colored four-blade propeller marked a giant X right on its nose. Pair that with the delicate wood and fabric of a vintage 1920s homebuilt, and it brought to mind images of Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2s from more than a decade earlier. Walking around it, we watched the light reflect off the gorgeous golden wood from different angles, playing on the curves and lines and the big samara-shaped paddle blades. In case you were wondering, samaras are the maple seed pods that descend slowly like miniature helicopters.

Based on the trampled path in the grass, we were far from the only ones enamored with Dan’s plane. Over the next several days, we found our eyes turning back toward the black and yellow Piet with the unusual prop. It sounded different than the other Model A powered Piets, with a lower hum, more of a purr almost, on takeoff. Combined with the brass fittings of the Model A engine and the vertical radiator limiting the forward view, it conjured up a time when aircraft were more mystical and eccentric—when the evolution of aerospace was more a thumbnail “that looks about right” rather than spreadsheets. As the sun was rising and the early morning fog was lifting, one could be forgiven thinking it was a century earlier.

1929 Revisited

Inspired by the original nostalgia, charm and mystique of the Pietenpol Air Camper, Dan decided to build one as close to the original 1929 plans as he could, including powering it with a liquid-cooled Ford Model A engine. After 10 years of construction, its first flight was in 2010. At that time, Dan was living in Poplar Grove, Illinois, which made for a short commute to the annual Pietenpol fly-in at Brodhead, Wisconsin, as well as AirVenture. However, he later moved to Puryear, Tennessee, which made for a very long cross-country in a 50-hp aircraft. Not dissuaded, he made the trip three times over the years, from Tennessee to Wisconsin and back.

During his Air Camper’s construction, in 2006 or 2007, Dan attended AirVenture and saw a forum entitled “How to Build a Propeller,” taught by Jerry Thornhill. “Making a propeller seemed like a black art, and I was fascinated,” Dan said. “I camped out there for the three days of the forum, attended every class and watched Jerry build a prop. I took lots of pictures and notes!”

Upon returning home, Dan made his first attempt at crafting a propeller. “It didn’t turn out so well,” he recalled. In going over the issues, he decided his preparation wasn’t as good as it needed to be and the glue joints weren’t up to the needed standards, but he viewed it as a great learning experience and practice. One big learning point was to avoid over-lubricating the chain saw as the overspray will cause the wood to become oil-soaked and will later prevent varnish from adhering to it.

After a bit more practice, he made a second attempt with a great deal more success. It had a curved shape and was constructed from ash. The shape came from a “drop-dead gorgeous” propeller he had seen on an antique engine on a stand at Brodhead years earlier. He’d taken a photograph of it and then scaled it up to full size by printing the photograph, tracing the propeller outline onto a blank sheet and then scaling the measurements up to full size to make a template. Dan carved one side completely and then marked it every six inches, making a template at each site, and transferred that information over to the other blade as it was slowly set free from the wood blank.

When completed, Dan added a dark mahogany stain to the finish to give it a period-appropriate look that accented the Pietenpol’s overall golden-age motif. His Pietenpol made its first flight behind this prop as well as many more hours in the air over the next 10 years. Dan’s skill soon had other Pietenpol aficionados coming to him for advice or to make props for their own aircraft. He kept trying different designs and kept gaining knowledge and experience.

All well and good, but Dan isn’t someone to leave well enough alone. “I was fascinated by the four-blade propellers of WW-I aircraft. I just thought they looked cool.” As he gained more experience building propellers, he thought he’d try making one with more than two blades. In 2013 he attempted his first four-blade design. “It was OK, but really not what I was looking for. It was too big, too heavy and had too high a pitch. It just wasn’t good enough.” After flying it for 10 hours, it came off and the two-blade prop went back on.

Four-Blade Prop, Take Two

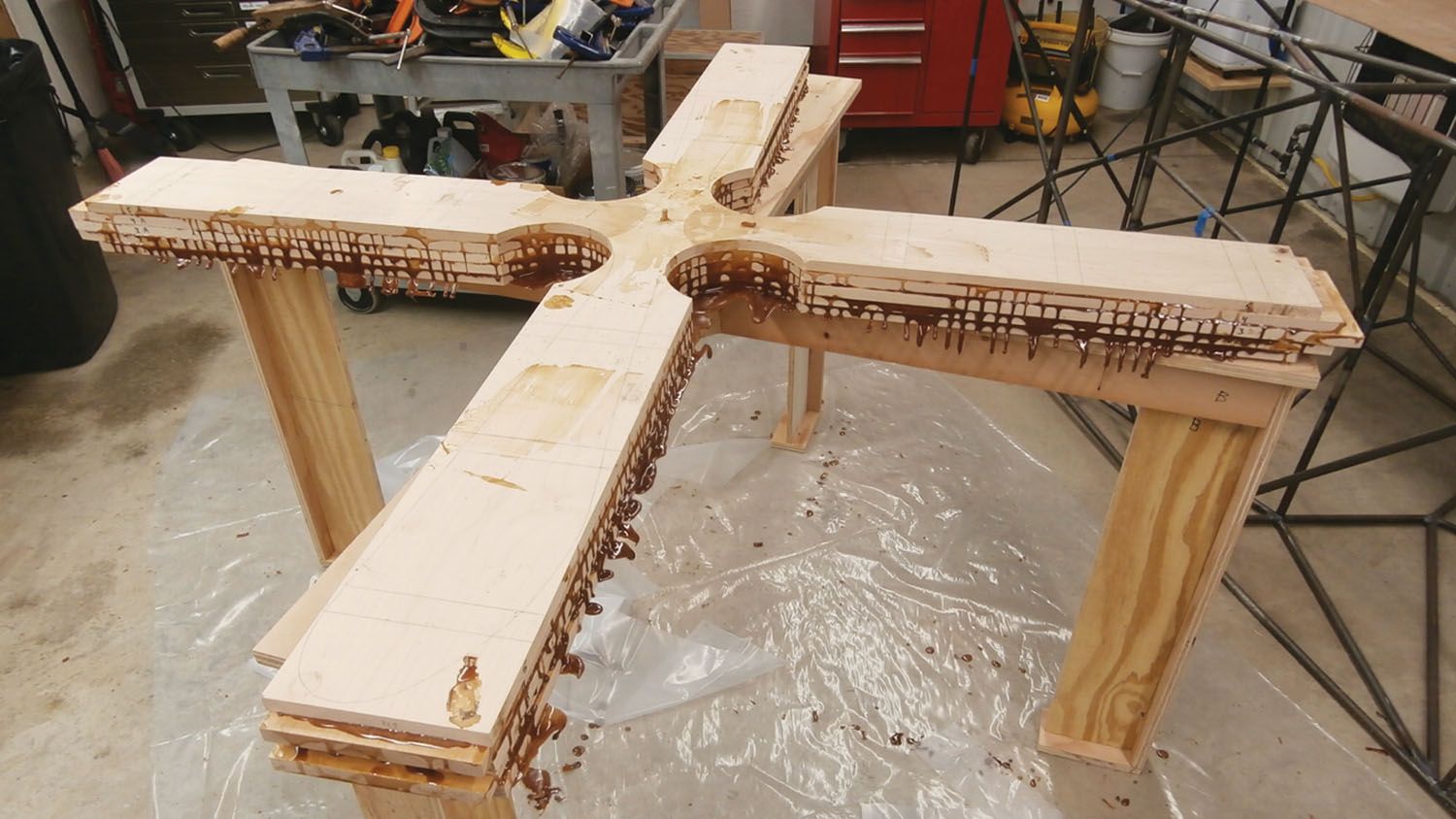

Over the winter of 2020 Dan decided to try making another four-blade prop with an eye toward keeping things proportional and light, with a smaller diameter and decreased pitch. Using 1×8-inch hard maple, he planed each board down from 3/4-inch thickness to 1/2 inch. Like all of his propellers, the wood planks were joined with Weldwood Plastic Resin Glue as previously recommended by Jerry Thornhill. Each piece of wood is balanced so that the heavy ends offset each other. Once glued together, the template for the blade shape is drawn onto each limb and then band sawn into shape. At this stage it looks like a cumbersome two-dimensional child’s toy.

The leading and trailing edge lines are carefully measured and marked with pencil, never ink or magic marker, which will stain the final product. The excess wood of one blade is carefully debulked with a chain saw down to the rough shape of the airfoil. Careful sanding follows, gently bringing the blade to life from the wood. Once the first blade was completed, stations were marked every six inches and templates made. Using those measurements, the shape and airfoil were duplicated on the next three blades. Stacking the laminations ultimately left Dan with a hub thickness of 3-1/8 inches, and he planed each blade down as thin as he dared. In the end the prop measured 68 inches in diameter with a pitch of 41 inches. After it was completed, it was only 4 pounds over the weight of his two-blade prop. That’s pretty impressive when you consider the gain of two extra blades!

So how does his Piet perform with the new prop? “Well, I can’t really tell much of a difference, honestly,” said Dan. “It is definitely quieter. It has a cool sound, sort of like the “thrum” of an Irish bodhran drum. I’m not sure if it comes from breaking up the exhaust gases, but it sounds nice.” Using a fish scale, he’s measured the static thrust. With his old prop it was 285 pounds, and with the new one it’s 240 pounds. However, he’s not sure if it is truly a difference as there really doesn’t seem to be any difference in flight.

The Pietenpol isn’t really known for its performance, and Dan has an air-actuated airspeed indicator, which he freely admits is more for show than accurate information (but it does look perfect). He hasn’t noticed any difference in his climb or cruise speeds. However, it does gain even more attention at fly-ins now, as it seems everyone does a double take looking at that unique prop!

Ready to Build Your Own?

Dan took all of his notes, pictures, and experience and put it together in a book called Propeller Carving—The All Power Tool Method. His goal was to create a how-to guide that essentially spoon-feeds what he’s learned about building propellers to people who are interested. “Most of the books I found when I got started were more theoretical with lots of math and charts,” he explained. “That wasn’t what I wanted. I wanted a step-by-step approach for someone who knows nothing about how to build a propeller but really wants to do it.” Dan’s book is available as an e-book or on CD from Aircraft Technical Book Company.

Another good resource is NACA Technical Note No. 212, which covers methods for determining what wood should be utilized in propeller construction based upon required speed (in rpm) and diameter for low-powered aircraft engines up to 50 hp.

Other resources for propeller construction include Propeller Making for the Amateur by Eric Clutton, Al Shubert’s booklet, How I Make Wood Propellers and, of course, Tony Bingelis’ publications.

Since he’s not one to sit idle or stand still, Dan is already deep into his next project: a Wittman Tailwind that will be powered by an O-320. And yes, he’s already built the propeller for it.

Appear to glaring errors or omissions in the side note on props:

“To go back to high school physics: Kinetic energy is defined as mass times velocity squared (KE = M x V²).

In less eye glazing terms, increasing the mass of air moved by increasing the diameter of the propeller is more efficient that increasing the velocity. ”

That does not make sense at all. Increasing prop diameter increases area by square, just like increase in speed.

“The advantage of fine pitch is that it provides more utility of engine torque and allows a higher rpm, so it winds up creating a higher airspeed and being more of a “cruise” propeller. In contrast, a coarse pitch prop, with its bigger bite, is often called a “climb prop,” ”

Exactly the opposite? Fine pitch = climb, course: cruise.