Anyone who has flown an RV-4 will tell you that the only thing that flies better than an RV-4 is a lighter RV-4. However, not many pilots will get the chance to fly a truly light one.

Anyone who has flown an RV-4 will tell you that the only thing that flies better than an RV-4 is a lighter RV-4. However, not many pilots will get the chance to fly a truly light one.

Van’s long-ago first brochures listed the weight of his 150-hp/wood-prop prototype at about 905 pounds, but that proved very difficult to achieve in the customer-built world. Most builders could not accept Van’s spartan ideas about interior comforts, instruments and other appointments and soon a 950-pound RV-4 was considered light. Then came bigger engines, constant-speed propellers, IFR instrumentation, full interiors and controls for both seats, and weights around 1000 pounds became common. (My neighbor’s RV-4, with an injected O-320 and a three-blade constant-speed composite prop, weighs 1015 pounds and performs very well indeed.)

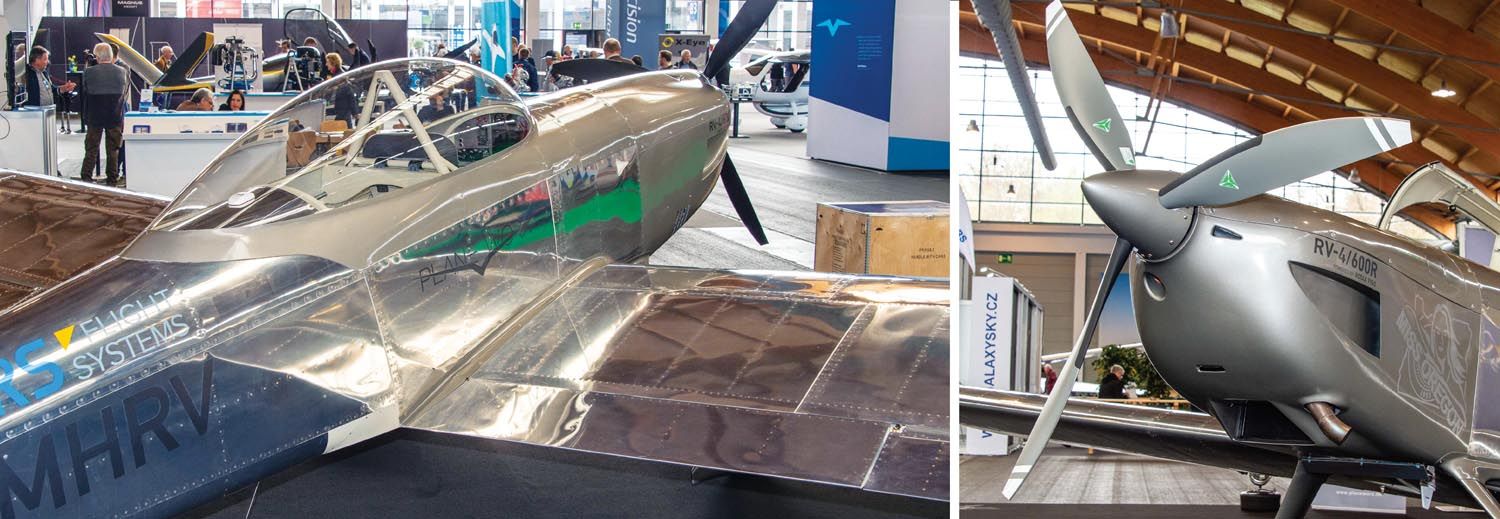

So now consider an RV-4 with a ballistic parachute, single-lever computerized power controls, three-blade constant-speed prop, fuel injection and 135 hp available at 15,000 feet. Sound good? Now imagine all that with an empty weight half a human lighter than Van’s bare-bones prototype!

That is exactly what German engineer Robert Haag has designed, built and flown. His RV-4/600 mates the time-tested RV-4 airframe with the Rotax 915 iS engine and the result is an RV-4 like nobody has seen before.

Robert, 45, was first introduced to airplanes by a family friend who was a flight instructor. “One trip to the airport…and the virus struck,” he says. At 15 he started flying gliders, then powered gliders, then more powerful airplanes, ending up with his own flight instructor rating. Graduating high school, he found an apprenticeship as an aircraft mechanic. Building on the hands-on experience, he returned to school and earned a degree in mechanical engineering. After 13 years in the R&D department of a fire truck manufacturer, he returned to his first love and began engineering, designing and prototype building Light Sport Aircraft. In 2015 he designed his own large hangar and built it on an airfield near Aalen, about 90 kilometers east of Stuttgart. Most of the space is dedicated to light-aircraft maintenance, but Robert kept some room for his own projects. One project in particular had been in the back of his mind for some time.

to his shop. That floor is waaay too clean.

Something Different

“Over the years I’d flown several RVs, and as Van says, ‘The smile never goes away,’” Robert noted. “But in Germany building an RV was becoming more difficult. The Lycoming engine requires avgas, which is getting harder to find in Europe and very expensive. The straight-exhaust Lycoming has difficulty meeting noise regulations. And of course, it is made in America, which means it must be imported into Germany, where shipping costs and taxes add to the already high prices. In my business I became very familiar with Rotax engines, which are made in Austria, not far from where I am based. I became very interested in the Rotax 915 iS. It was rated at 135 hp and because it was turbocharged, it could maintain that power up to higher altitudes. It was also approved for auto fuel. Best of all, it weighed a lot less.” (Actual engine installed weights are difficult to determine. In round numbers, a 160-hp O-320 with a prop governor, baffles and exhaust system weighs about 290 pounds. The Rotax 915 iS, similarly equipped, is just under 200 pounds—a delta of around 90 pounds.)

“I remembered flying an O-320 powered RV-4 and I thought if I made careful choices and did some good engineering, I could build an RV-4 that would meet the 600-kilogram (1320-pound) gross weight requirement of the German microlight category and still have enough capacity to be a useful aircraft. At the time a lot of microlight manufacturers were chasing a cruise speed of 160 knots.” Unlike the U.S. Light Sport category, German microlight regulations do not specify a speed limit and do not prohibit constant-speed props or retractable gear. “I thought the excellent aerodynamics of the RV, combined with the power of the Rotax 915 iS, might make that possible without having to use expensive composites or retractable landing gear. So in the late summer of 2019 I ordered a complete RV-4 kit.”

Building Quickly

COVID hit just as the RV-4 kit was delivered and, with a lot of time suddenly on his hands, Robert completed the basic airframe in just nine months. The airplane was pure Van’s from the firewall aft, with just a couple of exceptions. Robert found that Beringer wheels and brakes (made in Europe) were slightly lighter than the stock units in the kit, so he substituted those. A couple of minor modifications were made just forward of the canopy to accommodate the (required by German regulations) ballistic parachute.

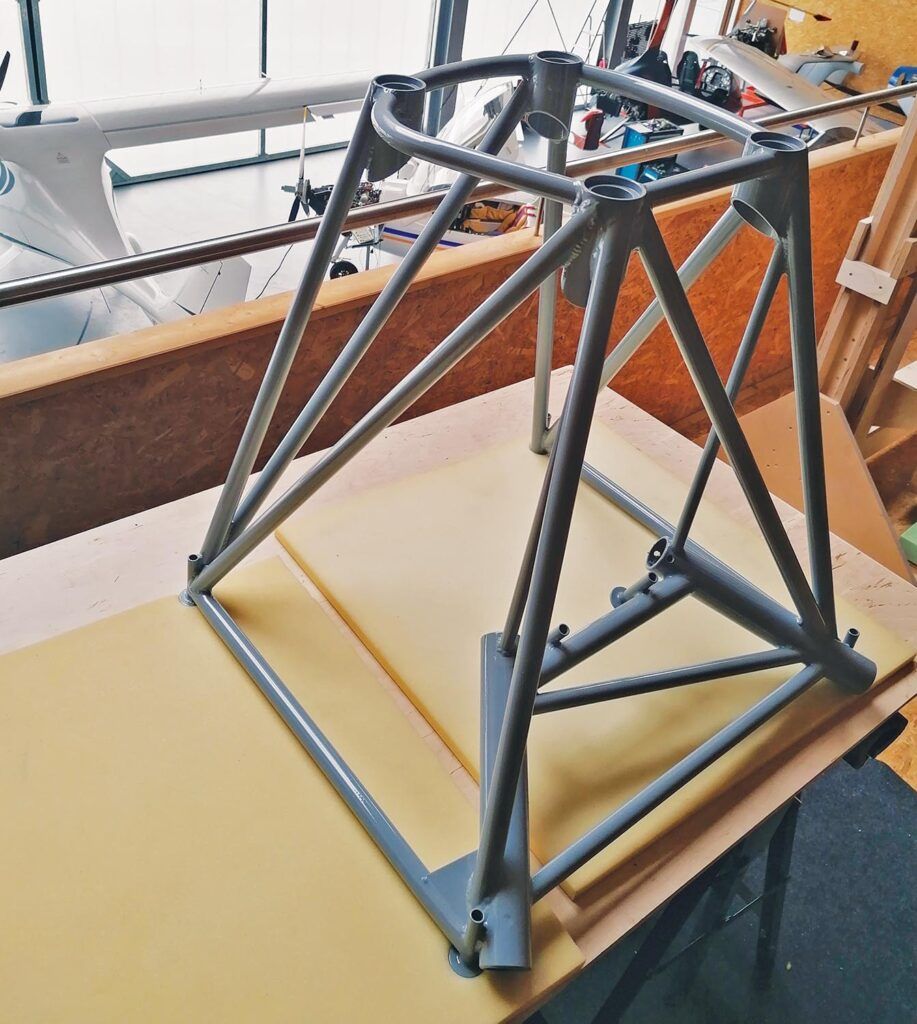

The parachute is a good example of Robert’s careful thought. It may seem strange to think that adding the weight of a parachute actually helps to build a very light RV-4. But just forward of the windscreen, the RV-4 has a removable panel. It opens to a bay originally designed to provide access to the back of “steam” instruments, some of which could be 12 or 13 inches long. The new glass displays extend only an inch or two behind the panel, and Robert was able to fit the chute and its propelling rocket into the remaining space. The attaching cables were connected to the engine mount and to the rear spar/fuselage attachment. The rear cables were run inside the cowling, then outside the fuselage to the wing. An extension of the fiberglass gear leg cuff covers the cable and makes the installation all but invisible. Keeping the parachute in this forward position meant the lighter engine did not have to move nearly so far forward to maintain the designed CG, which meant that added fuselage side area and weight could be kept to a minimum.

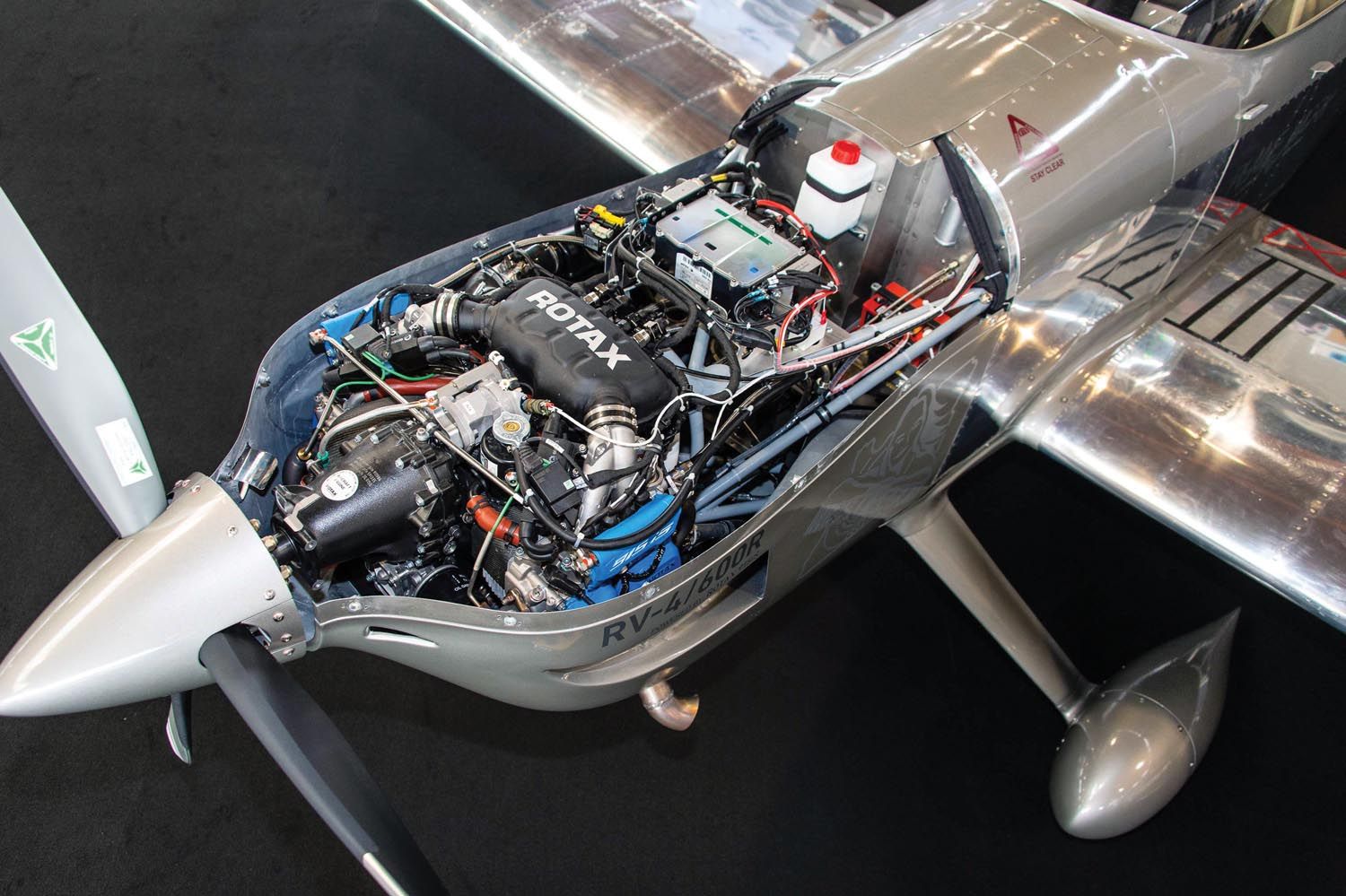

Rotax has managed a commendably compact engine package, but even so, fitting a turbocharger, intercooler, oil cooler, computer boxes, gear reduction drive, wiring harnesses, fluid lines, cooling ducts and…oh, yeah…a four-cylinder engine inside the firewall profile of an RV-4 was a tricky job. The photos show just how carefully every item had to be considered.

With the longer mount built and the engine installed, a new cowl was fabricated. That’s one sentence, but it represents many hours of work, making a positive plug, then making solid negative molds to lay up the glass cloth and epoxy. No less than ten air inlets were needed to cool the coolant radiator, oil cooler, turbocharger, turbo intercooler, cylinder bases and electronic “stuff.”

In the cockpit things are much simpler. A single lever controls power. Engine management—fuel flow, ignition timing, etc.—is controlled by the Rotax EMU. Optimum rpm is determined by a box from RS Flight Systems. This unit, increasingly seen in European Rotax-powered airplanes, uses several data points delivered by the ECU to determine the desired rpm and controls the standard hydraulic governor with an electric servo.

You Pays Your Money…

With any aviation engine today, there is always the nasty question of money. You might expect that a complex European engine like the Rotax would be expensive: You wouldn’t be wrong. The list price for a 915 iS in the U.S. is $43,000 and change. (If you need 10 more horsepower, the newly released Rotax 916 iS, with identical weight and size specs, will set you back about $50,000.) But if you think the traditional American engine is less expensive, think again. Van’s Aircraft has a long-established OEM agreement with Lycoming and sells factory-new engines for the best prices around…if you are building an RV. A new IO-320 with dual electronic ignition and an exhaust system lists for $43,750. None of these prices include shipping nor do they include the myriad of bits that are required to make the engine actually fly. Lycoming’s TBO is 2000 hours while the 915 iS’s is 1200 hours. You can get a good food fight going over the relative merits of a fast-turning, gear-reduced, fairly complex, computer-controlled engine designed in the 21st century versus a slow-turning direct-drive engine that’s about as complex as a stone ax and has its design roots in an era where computers were people with pencils and big erasers. In the end, you pays your money and you takes your choice.

How Does It Fly?

After all the challenging work of building the airframe and fitting the unique engine was done, the airplane was ready to fly. Unpainted and tanks empty, it weighed just 814 pounds, making it very possibly the lightest RV-4 ever built…lighter than many RV-3s.

“I was concerned that adding forward fuselage area might upset the RV control harmony, especially in yaw,” Robert said. “I worked very carefully and in the end I had to lengthen the cowl just 10 inches to make the CG balance out. With the more pointed cowl, the added side area is not that much. Still, it is not nothing, so I was anxious to see if it made a difference in flying qualities. I am happy to say it flies beautifully.

“I have flown over 50 hours and my worries about yaw stability seem to have been unnecessary. I have flown spin tests and the airplane recovers quickly and normally—I must mention though that I have never spun a Lycoming RV-4 so I can’t say if my RV-4/600 is different. The climb performance is better than with the O-320. True airspeeds at altitude are higher too, courtesy of the Rotax turbo…high enough that I must reduce power to remain under the Vne limit, starting at about 12,000 feet.”

So, can you, too, build and enjoy an RV-4/600? It is increasingly possible. Now that Robert has the molds for the cowl and the jig for the welded engine mount, he intends to make those parts available. He notes that “while it will take longer to build an RV-4 than other RVs because the kit is not prepunched, it should not take longer to build an RV-4/600 than a stock RV-4.” According to the “Hobbs Meter” on Van’s website, 1452 RV-4s have been built, so any RV-4/600 builder will be following a well-trodden path, at least as far as building the airframe is concerned.

And what about those “other RVs”? Well, Rotax has always intended the 915/916 series as direct competition for the Lycoming O-320/360, so their engines should work well in any RV intended for 150/160 hp. In fact, they are already flying. An RV-7 with a 915 iS is flying in Argentina and for some time experiments have been underway in Florida with an RV-9A powered by a similar engine. With its longer wing, the RV-9 and the turbo’d engine might be a particularly happy match. (How about the RV-8? The author has flown RV-8s with five different engines, ranging from 160 hp to 220+. My favorite, hands down, was a very light RV-8 with an O-320 swinging a metal constant-speed prop. The thought of that airplane weighing 120 pounds less is positively exciting…) An inverted oil system is under development that will enable aerobatic pilots to take full advantage of the lighter engine.

The whirring sound of the turbocharged Rotax is still unusual at American airports, but that may be changing more quickly than anyone envisioned. Builders like Robert Haag have given us a look at what’s possible with a modern internal combustion engine, engineering skill and good craftsmanship. At least until practical electric propulsion becomes possible, it might be the way forward.

I believe the tbo is now 2000 hours on the 915is.

Rotax has been saying it will increase the 915’s TBO but we haven’t seen documentation of that yet.

Beautiful work.

….we drive experimental aircraft. TBO is just a made up number.

I am inexperienced but I get the impression that Lycomings and Continentals don’t always or even very often make it to TBO without significant repair/part replacement.

So how does the cruise and rate of climb compare to a light 150hp RV-4? I’m building a -4 currently and would love to know some more details.

The 915 is 141 horsepower.

That number is max/5 minute power. but the engine is rated for 135hp continuous. The newer 916 is rated @ 137hp continuous.

Thanks for the great story. I saw something about this on the Van’s forum and was looking for more details on the project. I had no idea he was able fit a parachute as well. Rotax owners seem pretty happy with their engines.

How to get in touch with Robert, regarding the inverted oil system for a Rotax 915.