Technically, it is an airplane—wings, engines, N-number and all that, but it doesn’t necessarily act like other airplanes, and you don’t fly it like you would other airplanes. It’s an AirCam, the world’s heaviest ultralight, a twin that, without doubt or even casual competition, many would say gives passengers the most enjoyable and entertaining ride of any airplane out there. Oh, and they’re not masts; they’re cabane struts.

Way back when, I got a ride in an AirCam at Florida’s annual Sun ’n Fun fly-in, and it was a hoot! Great view of the pine forests around Lakeland, no obstructions to seeing the ultralight traffic on all sides, chilly in the back with me wearing shorts and no jacket even though the temperature was in the mid-70s. It made an impression, the introduction to an addiction.

AirCam patterns can be much tighter than in faster airplanes, and it helps you stay out of their way, especially when your cruise speed is slower than their pattern speed. The piece of acrylic with the bent tab is not to control back seat wind; it is a structural stiffener for the diagonal tube, which is there to keep the wing and engines off the pilot in case of an accident.

A few years later, we were on short final at Sun ’n Fun when the flagman controlling ground traffic motioned an AirCam into position on the runway. Just as we were on very short final, the AirCam was cleared for takeoff. Two plumes of dust erupted behind it like solid-rocket exhausts, and by the time we touched down, it was like totally gone, dude—past the other end of the runway and leveling off at pattern altitude.

Once I saw an AirCam take off right after we had parked our law-abiding Cessna dead-center in a proper place on the ramp. The AirCam taxied to the end of the runway, waited a minute, and then took off as if all of the runway past the numbers was a minefield. Before it got to the first turnoff, the AirCam had turned crosswind, reduced power to cruise, and was no longer concerned with lesser aircraft, traffic patterns, altitudes or a prolonged climb and acceleration to cruise.

So if your background includes a lot of instrument flying, some aerobatics, flight evaluations, single and twin seaplanes, and a bunch of time in a Van’s RV-4, what’s the next logical step in your aviation progression? A jet? Ha! A low and slow AirCam, of course. With its wide open cockpit, it’s like flying in the bow of a canoe behind a motorcycle windshield.

The Search Is On

One day I’m killing time on the computer, surfing the web, and I do a search for “AirCam for sale.” Bingo! One turned up at a U.S. Marshall’s auction in Midland, Texas, so I drove there to check it out. The plane was a drug-seizure asset. I got to look at it, but not really inspect it. I did get to see that both engines ran, and the plane had logbooks.

Ah, yes, the joys of winter flying in the AirCam. Fuel? Check. Weather? Check. Parka and wooly socks? You bet.

I wrote a bid that left room for me to put some money into the plane for unforeseen fix-em-ups, went to the bank for a $6000, non-refundable deposit and sent in the bid. Within days, I got the phone call, and I was an AirCam owner…or I would be when they got the rest of the money.

Happy Homecoming

The next step was to get it home. I arranged to have a condition inspection started, and the first problem surfaced: insurance.

Turns out that aircraft insurance is grouped into like-kind aircraft. The NTSB records included two AirCam accidents, one a wire strike leading to a crash in a lake—miraculously, not fatal—and another where fuel shutoff valves installed in the engine nacelles were not controllable from the cockpit. That plane took off with the electric boost pumps on, which bypassed the shutoff valves, and when both pumps were shut off, the engines quit because the valves were off. I had 140 hours of multi, ATP/AMEL and CFI/ME, but still I struggled to find hull coverage. Eventually, with the help of the good folks at Falcon Insurance, I was covered.

Runways have an immediacy when you can see every crack and pebble. A normal takeoff would have you in the air before you passed the runway numbers.

The late Fred Michna, CFI, graciously gave me an abbreviated checkout that comprised three times around the pattern, never getting above 500 feet AGL. (It was too cold for him to endure any more of the back seat than absolutely necessary.) The front airspeed indicator had problems, and showed 35 mph on short final and went to zero in the flare, but I had enough experience with Cubs, L-2s and gliders that I made three good landings. Because a “real” checkout wasn’t in the cards, and the insurance wanted me to have 20 hours solo before I took passengers, I figured that I would check myself out, much as glider pilots do. (At that point, I’d flown maybe 140 makes and models of aircraft and had more than 2500 hours.)

Short final into Tipton on a warm summer’s day. The crosswind is nearly always from the right, so the right throttle comes up and the left goes back right about here. Holding power on very short final and sometimes right up to touchdown does increase the landing roll.

Next morning, it was time to head west toward home in Arizona. One possibility was a direct route, but the first leg would be 3 hours with few landmarks in a new airplane, and with no other airports en route. Plan B was to fly along Interstate 10, using it as a navigational aid between airports about an hour apart. The only trouble was that I wasn’t sure if the wind in the cockpit would allow me to open a chart, so I memorized the details of each destination airport before takeoff. I also had a Garmin GPSMAP 396 that would have given me all that airport information, but it was new and I hadn’t yet learned that feature.

Here We Go

The engines started with the characteristic Rotax burst of speed, but the right tachometer showed zero with the engine running. Grrr. The late John Weiler, AirCam owner and gracious crew chief, helped take the nose bowl off, tighten the crimp fitting and push it back onto the pin on the tachometer. Taxi out, nobody around, line up, power up, tail up, liftoff, no need to push the power any further forward, 200 feet, turn west, cruise power, and we’re off on the first leg, 90 miles to Pecos, Texas.

With ski bib overalls, a parka and many layers, I wasn’t too cold, but it was definitely sensory overload: the view, the abundant fresh air, the continuous airframe buffeting that seems to be part of AirCam flying, the gleeful greeting to every gust and, of course, the navigation and flying. The flying was easy and simple, but after that first 90-minute leg, I needed a nap. In fact, I took a nap at every stop along the way.

Turning final for a stop and go. With the hangar at the other end of the runway, long—really long—landings are common. It also helps to have the cooperation and trust of great folks in the Cedar Rapids tower, who probably think of the AirCam as comic relief from a daily diet of regional jets.

Part of why it was slow were the wind irregularities down low. I discovered that wind will pick up over hills and in valleys, and at one point, I saw a groundspeed of 33 knots, somewhat less than my cruise speed of 65. “Real” airplanes don’t see these phenomena, because they don’t fly that low. I suspect that those who are unaware of such phenomena are sometimes fatally surprised by them.

As I got more into New Mexico and Arizona, the AirCam started to unlock the West. There were the occasional grand vistas of completely undeveloped, wide open space, not even a fence line to scar the landscape, but there were also many grand vistas littered with McMansions on two-acre lots. On one leg, I smelled my first wood fire from the AirCam. That night, I stayed with friends in San Manuel, Arizona, a tiny town northeast of Tucson. Navigation was easy along I-10, but then I had to go cross-country for a ways.

Day three got me home and was also my first encounter with tower-controlled airports in the AirCam. I have no problem with towers; it’s just that the AirCam is so slow. The first towered stop was (Williams) Gateway airport, southeast of Phoenix. I called in “15 mile final, slow, unfamiliar.” Tower controllers immediately vectored me to the west to get me out of everybody’s way. At least, until I asked for a long landing, and then they told me to use Taxiway Romeo, as if I knew where that was.

A balaclava and a snowmobile suit are Wischmeyer’s choice of garb on a 50° day, the latter as much for its windproofing as for its warmth. Note the relatively complete set of back seat instruments. All that’s missing back there is a GPS for course guidance.

Leaving Gateway, I had to climb to more than 1000 feet AGL to be legal for terrain clearance over a congested area. That’s when I discovered that somewhere inside the AirCam fuselage is an ingenious little mechanism that senses how high you are above the ground and makes the fuselage get narrower. The same thing happens when you hit a bump that lifts you up against the seatbelt. If you’re in sensory overload, cold and fatigued, with a basic fear of heights…well, you get the idea.

Learning Low Flying

Back home in Prescott, Arizona, with 11 hours in the AirCam, it was time to really start learning the airplane, and the high desert was a great place to do it. The challenge was not in flying the airplane, but in getting comfortable and learning about the airplane safely, which meant slowly and carefully.

The AirCam is not your ace cross-country airplane, and it’s not an acro ship. Basically, it’s like a twin-engine Cub, and flying it well involves all those factors you read about early in your career—only more so. Bumps in other planes are prolonged encounters in the AirCam, and if one wing hits a thermal, you’ll hold opposite aileron for a few seconds till you get through it, using some rudder to help. Do a steep turn, and you’ll need power—lots of it—because instead of merely losing speed like you would in another airplane, you’ll run out of speed in the AirCam.

Not that Iowa summers are all that warm (note the heavy jacket), but it was warm enough for short pants. The back-seater has to really turn in his seat to take air to air photographs, in this case, of an RV-8A flying v-e-r-y slowly with full flaps.

The two biggest safety considerations are obstacles and wind, and obstacles are by far the most dangerous. Over rural northern Arizona, there are plenty of places where flying low (50 feet) is neither immoral, nor contrary to the strictures of FAR 91.119. There are few cattle, and they’re usually too dumb to panic, unlike deer and especially coyotes, which hide under bushes. So mostly what you have to watch out for is yourself and the occasional hawk or raven. And there are plenty of places where there is no earthly reason for a power line to traverse the landscape, but there it is. It only takes one, so I quickly adopted the rule of no low flying over unknown routes.

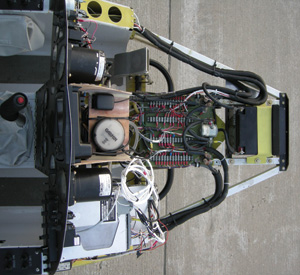

The rewired instrument panel. GPS and XM antennas are on a shelf behind the Garmin 396 GPS, and forward (right in the picture) are the four terminal strips, each outer strip handling a 12-wire cable to that side’s engine. The wiring could be tidier if the author had been willing to rewire the entire plane instead of just the panel.

Fast-forward to Iowa, my new home, where Cedar Rapids and surrounds are full of cell-phone towers, unpainted and sans strobe, plus the normal high-tension cables, phone lines and a handful of tall TV towers. Add a zero to the 50-foot Arizona cruising altitude, plus a little extra for rising terrain to get my standard altitude for safety and compliance.

From this cruise altitude evolves the theory of best altitude for observation. Flying in the AirCam at 50 feet gives more of a macro perspective, but 50 feet is so low that you have to spend too much attention to flying the airplane to really appreciate and absorb the view; 500 feet is certainly too high, and 150 feet is maybe the best AirCam altitude. The nice part is that twin engines reduce the risk of flying low, though they don’t eliminate it.

Last summer’s project was building time, as there had been several attractive jobs that required 100 flight hours in the last 12 months, and I was woefully short. So, after starting the quest to build hours with a 25-hour round trip back to Arizona in the Cessna, my AirCam summer began.

The logbook showed 47 AirCam hours at the start of the year, but there are now 55 more, from flying nearly every time the visibility was good and the surface winds were forecast to be 10 or less. All of this recent experience has lessened that tendency to narrow the fuselage, and my comfort, confidence and experience are way up even though the AirCam has the aerodynamics of a Whiffle ball. I’ve also learned that because the AirCam, like other very slow airplanes, has an overbanking tendency, this means that if you’re flying a very tight pattern, you can turn final at too low an altitude and have to really work to get the wings level before touchdown.

If it’s cold enough that you need ski bib overalls or a snowmobile suit on the ground, it’s too cold to fly. But these are the order of the day when it gets down to the 50s and below, especially if it’s cloudy or if you’re in the shade of the wing. Most passengers have jackets that are warm enough. Only one hat has blown off a passenger so far.

It’s Not Heaven

Iowa, though it’s not really AirCam country because of the cold half the year and the altitude limitations, is still pretty wonderful from the air. The upper Midwest in the summer is as beautiful as countryside gets. One night, I blew my stresses away, flying out past the farm with all the ponds, the one-lane humped bridge over the railroad track, beyond the farm with the million rolls of hay, and tidy country cemeteries with the grass immaculately mowed, and then 20 miles west to intercept the Iowa River, with the power pulled back not just because of the tailwind, but because there’s no point in rushing the view. Flying landscape patrol solo in the AirCam is much more fun than flying solo in anything else.

Back along the Iowa River, there are occasional fishermen in the winding channel. We saw a perched bald eagle here earlier, and Marengo is where there was a tornado this spring. The deer come out of the forest to forage in the corn fields at dusk, and there’s an old steel truss bridge that is often underwater when the rains come. But today, when the water is calm, it seems to float in space, reflected symmetry camouflaging its identity. Then it’s north to the airport where the AirCam provides comic relief for those who control Cedar Rapids’ Class C airspace. Traffic here is so sparse, it makes you wonder why there’s even a tower.

The AirCam is too slow to mix well with other traffic, but we’ve implicitly worked things out. I often tell the tower that I can circle to stay out of other people’s way, and one of my standard requests is a short approach to a long landing. On Runway 13, I’ll turn final with about 2500 feet of runway left, and easily touch down on the markers for, you guessed it, Runway 31. As the AirCam slows to taxi speed, the remaining runway is more than twice the distance I need for takeoff. One day, flying solo and with a 12-mph headwind, the takeoff roll was 60 feet, 20 yards. When there’s a new controller in the tower who doesn’t understand, I’ll use Runway 9, right in front of the tower, and let them see the 200-foot takeoff roll.

The new instrument panel, really sweet for the purpose. If the author had it to do over, he’d move the flap switch from the left side panel and put it next to the fuel pumps on the left of the main panel, as the flap and pump switches are about the only checklist items once the runup is completed.

Just after takeoff, I usually reduce power in the climb to keep the deck angle under control. Normal cruise is 4200 rpm (out of 5800) giving 70 mph, but you can add some (less than full) power, maintain 70 mph and climb at 800 feet per minute, giving new meaning to the term cruise climb.

The vertical fin is huge—8 feet, 4 inches to the top—to give control at low airspeeds with one engine out. The downside is that the huge fin makes the AirCam clumsy to taxi in a crosswind and limits its crosswind capability. Using differential thrust is standard on taxi and landings.

What’s Next?

The AirCam has given me 55 hours of genuine multi-engine time, burning a whopping 6 gph. Total. This has pushed the logbook past 100 hours in the last 12 months, past 3000 hours total time, past 250 hours of multi-engine time. The insurance underwriters seem to consider all multi-engine time interchangeable.

In Iowa, maybe 30 people have flown with me, and all have had the time of their lives. When my wife and I were separated, and after she had filed the divorce papers, I still called her up to offer a ride just because it was such an experience. I didn’t want her to miss seeing the herds of pronghorn antelope, the Verde River canyon, Jerome and Granite Creek. After we landed, she said, “That’s the most fun flying there is.”

But Iowa is again giving up its annual dalliance with warm weather, and more and more, when I fly the AirCam, I have to wear long pants under the snowmobile suit. There’s little point in owning an airplane that hibernates in the hangar half the year, so I hope the AirCam moves south soon to an area of temperate climate, open airspace, low wind, willing riders, beautiful scenery and a territory worth exploring. And I hope it takes me with it.

Two engines, the whole point of the AirCam. But you need a multi-engine rating to fly it, as well as a tailwheel endorsement. AirCam time counts as multi-engine time, just like any other twin.

For more information, call Lockwood Aircraft at 863/655-4242, or visit www.aircam.com.