Plenty of thought goes into building an airplane, and many of those thoughts concern engines. If “What airplane do I want to build?” is the first question in homebuilding, then “What engine will I power it with?” has to be the second.

It’s natural. No other single point in an aircraft drives so much of its performance, personality, cost, safety, and resale as its propulsion. Even from a purely technical viewpoint, the engine sits in the middle of a three dimensional Venn diagram of hoses, wires, mounts, accessories, pipes, cowlings, and on and on. With so many interlaced considerations, it’s no wonder we spend so much time mentally wandering in the engine thicket.

So consider this buyer’s guide a verbal machete for hacking through the major vines in the engine undergrowth. We’re presenting the major engine considerations so you can better frame your engine buying decision, plus a comprehensive list of available powerplants.

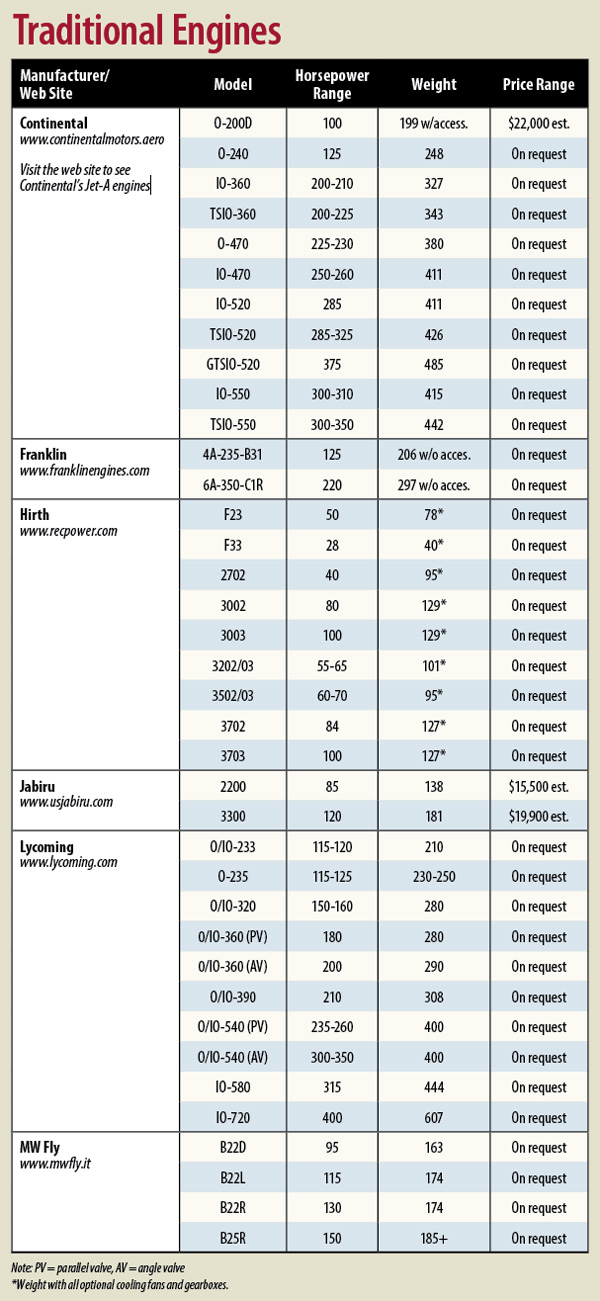

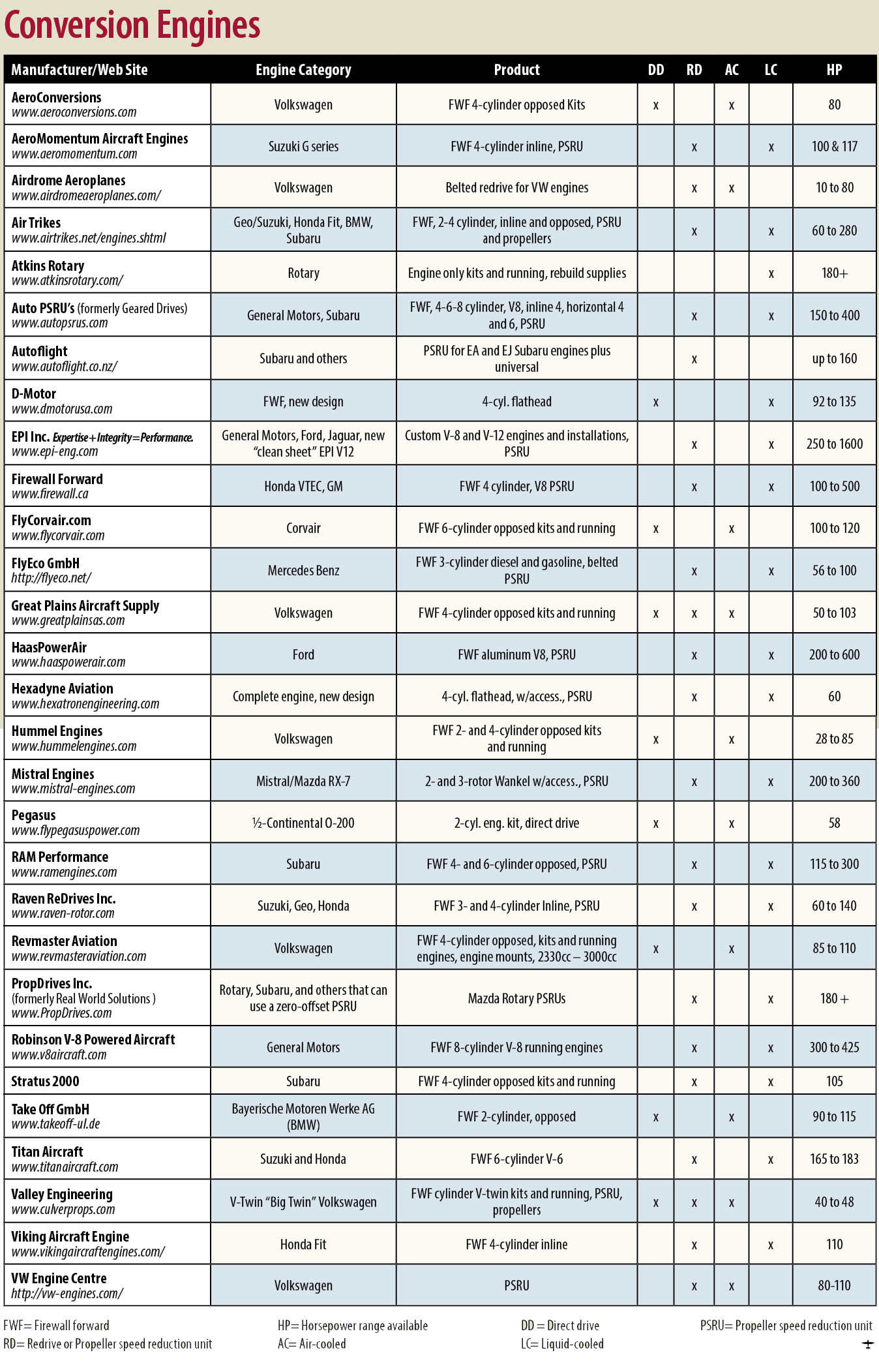

To keep the subject manageable we’ve broken the engine market into two broad camps. The first is traditional engines, the ones designed from the beginning to power aircraft. The expected Continentals, Lycomings, and Rotaxs are found there. The second group is for engines originally designed for something other than aviation, but converted to slipping the surly bonds.

Selecting an Engine for Kit Aircraft

There’s no one prime consideration in picking an engine, but practically speaking the choices narrow rapidly once the airframe has been chosen. For the crowds of RV builders, the choice was made a long time ago: Van’s insurance underwriters prefer the known quantity of Lycoming engines, so putting anything else in an RV (except an RV-12, which was designed for a Rotax 912 ULS) is praying for headwinds.

Something similar is in play with almost all other kit aircraft, including ultralights, LSAs, and other lightweights. The designer had an engine in mind when penning the airframe, so be it a Lyc, Continental, Rotax, Revmaster, or Hirth, the prevailing wind is blowing to a specific engine family, and only those seeking a specialized airplane or an increased building challenge need deviate from the kit designer’s intentions.

What About Plansbuilt Aircraft?

Because almost all new homebuilt designs are offered as kits, these days plansbuilt almost certainly means a heritage design such as a Thorp, Starduster, Tailwind, Cassutt, et al. These planes are designed around Lycomings and Continentals because that’s all there was when they were designed. On the other hand, the plans often leave the engine choice up to the builder, so it’s a correspondingly shorter stretch to reach for a Subaru or Chevy V-6 conversion if you’re building the firewall forward from scratch anyway.

Using the engine the kit or plans call for means far fewer building headaches, too. If you want to fly, rather than play powerplant development engineer for the next decade, the traditional choice for your airframe is the way to go. You’ll find parts and advice much easier to come by. Furthermore, assembling a kit is typically all the challenge many of us have the fortitude for; piling on a non-standard engine is typically too much.

Insurance and Resale

Insurance and resale are definitely affected by engine choice. Play the odd man and you’ll pay both ways. The FAA won’t be impressed either. Use a recognized engine and propeller combination and the fly-off time before the feds free your bird for flight about the country will be less. Drop in an auto conversion and typically the flight review stage jumps from 25 hours for a recognized engine (and propeller) to 40 hours for an auto conversion.

Of course, non-aviation engines have their strong points. If you’ve been in the airplane game forever and are ready for something new, an auto conversion will provide that challenge. Even better, if you’re understandably attracted by the newest technology, the only way to get that in a small aircraft engine is to roll your own using an auto conversion or, when they finally come to market and you have a six-figure engine budget, any of the new aircraft-specific engine designs currently in development.

Truly Experimental Experimentals

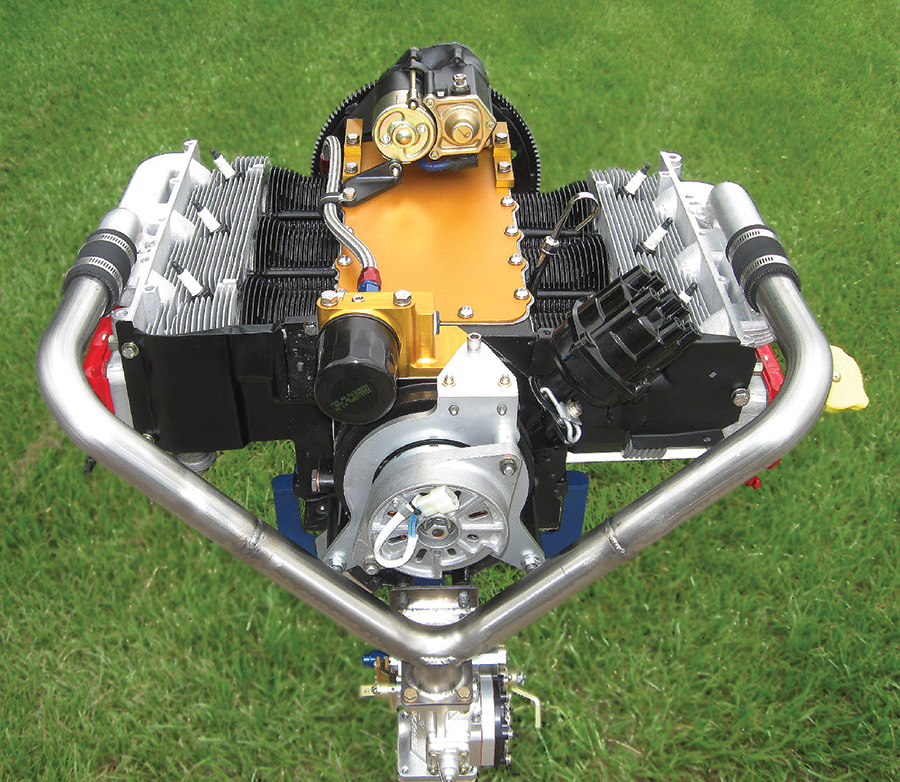

Typically these are small, high-efficiency designs-often one-offs or highly modified traditional planes-and powered with any number of smaller displacement, higher-revving engines from commuter cars, motorcycles, and snowmobiles. Or perhaps with no pistons whatsoever in the case of rotary, electric, and jet-powered amateur builds. There is no way a Lycoming will do for this class of experimenter, so enter the leading-edge of amateur aircraft engine development with their home-crafted mounts, induction, engine management, and propeller speed reduction units. This is a fascinating corner of Experimental aviation, where progress in affordable CNC machining, digitizing, and rapid-prototyping is pushing the boundaries of what a crafty, well-educated amateur can accomplish. But it’s really an end unto itself, as opposed to accessible personal aviation.

Clones and Strokers

Getting back in the mainstream, prospective Lycoming drivers will have the choice of clone and stroker engines. Clones are engines built by companies other than Lycoming, but using Lycoming architecture. Superior and Titan are the players here, and there’s no reason to shy away from them. Strokers use crankshafts with longer strokes for larger displacements, and thus more power, for essentially no weight or external size increase. Stroker is also sometimes used loosely to denote greater displacement from a larger bore, or a larger bore and stroke combination. In any case, there is typically more stress on the crank, rods, pistons, and cylinders from stroking, but apparently not enough to be of practical concern. Most buyers prefer the extra power and won’t fly enough to be concerned about possibly missing a few hours of TBO.

It takes fuel to make more power, however, so a larger-displacement stroker will burn more fuel than the standard-displacement version of that engine. Increased internal engine friction may not help range either. Strokers also cost more initially, thanks to their specialized internal parts, so you’ve got to want the extra power-you’ll know it if you’re a hot-rodder at heart.

The same is true with mildly raised compression ratios. Lycoming and Continental are not fans, but moving from 8.5 to 9.5:1 on compression doesn’t seem to stress engine internals enough to matter and really helps with fuel economy or increased power (you can never have both at the same time). Habitually cruising at 5000 feet or higher (the higher the better) is also prime time for higher compression. Many custom engine shops use 9.5 or 10:1 compression ratios as a matter of course these days. Don’t go higher unless you have a specific need, which you should discuss in detail with your engine shop.

So, if you want to get into the air in a safe traveling machine while you’re still young enough to climb up on the wing, sticking with a proven engine (and prop) is the way to go. If you’ve already got thousands of hours in your logbooks and a plane in the hangar, maybe trying something a little different on an existing airframe is the challenge you’re looking for. If your outlook is more akin to Orville and Wilbur’s trail-busting engineering, then private aviation is open to whatever engine you select for the job.

Traditional Engines, New Choices

So you’re in the market for a purpose-built airplane engine-a fine choice. Here’s what’s new in the non-certified, Experimental engine market.

Lycoming

For mainstream giant Lycoming, the movement today in Experimentals is toward proven combinations, pre-assembled, and ready-to-run. These time-honored choices are offered by Lycoming themselves via their standard off-the-menu line of Experimental engines. You’ll find them offered direct through Lycoming, their dealers such as Van’s, and custom engine shops.

Thunderbolt is another Lycoming Experimental-only option. To compete with the well-established custom shops around the country (Barrett, Ly-Con, etc.), Lycoming runs their own in-house hot rod engine shop. With access to all Lycoming parts, plus whatever aftermarket parts it wants (namely ignitions and fuel systems), this factory specialty shop offers a selection of both off-the-rack and custom engines of all descriptions. Mild-to-wild as they say, a Thunderbolt engine can be nothing more than paint-and-chrome dress-up, or a deep-breather for competition aerobatics.

Continental

Unlike Lycoming, Continental has traditionally not supported Experimental engines, save for some action readying their O-200 for Light Sport use. Lately they’ve focused on developing certified diesel engines acquired in Europe, so their sole Experimental engine remains the O-200D lightweight version of the ubiquitous O-200. You’ll still see plenty of certified Continentals in Lancairs and other go-fasts in the form of the deep-breathing IO-550. Many of these are built by custom shops as Experimental engines and are very powerful.

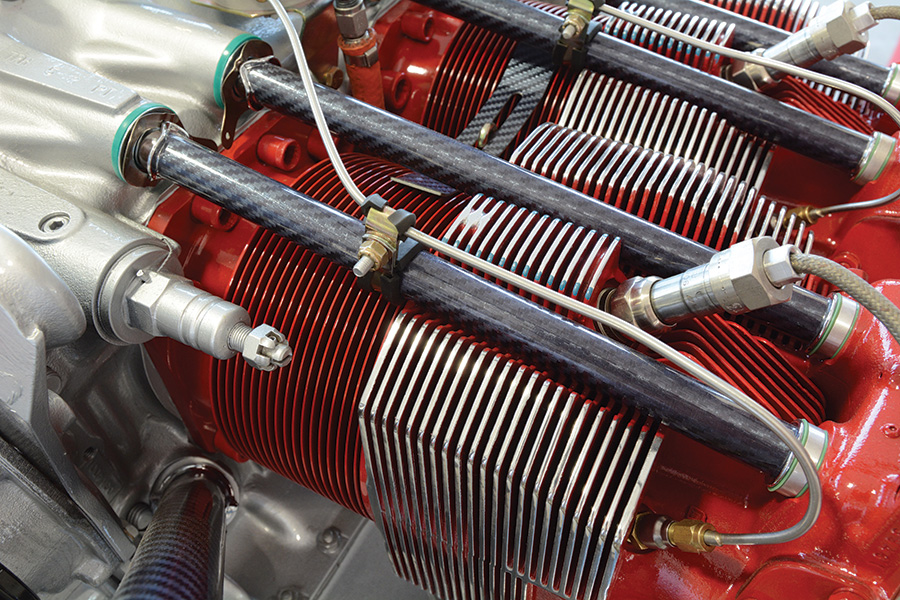

Thunderbolt engines from Lycoming’s custom shop can include almost anything you want, including carbon-fiber dipstick tubes.

Superior

Much of the action in traditional engines is now coming out of the Lone Star state where clone engines are strong sellers. At Superior, the news in Experimental engines-not to overlook they just certified their 180-hp 360 with considerable fanfare-is a new 382-cubic-inch four-cylinder. Superior says their engine shop customers had been asking for something between their bread-and-butter 180-hp 360 and pricey 215-hp 400 stroker. Our take is the 382 can be thought of as a notably less expensive, but still premium, version of the 400. It uses a counterweighted stroker crankshaft, roller lifters, and 360 parallel-valve cylinders, and is rated at 200 hp. Superior says it’s “good on weight,” and with 9:1 compression and direct drive, they’re figuring on a 2000-hour TBO.

Asked if any of the parts are Chinese-sourced, Superior says no. A long-time Texas company, Superior is now Chinese owned, but apparently in a hands-off way. As with their other engines, the 382 is built from all new parts sourced from wherever makes sense, but so far, that’s not from China. The crank is forged in Germany, the valves are Italian, and the cylinders made in the U.S., along with most of the rest of the engine. Pricing and a release date for the 382 were not set at press time, but expect the engine in calendar year 2015. It seems a natural for the surprisingly numerous builders wanting “a little more” than a garden-variety O-360, but not ready to spring for a 400.

In 2014, Superior gained certification for the 180-hp IO-360 Vantage engine. Their 200-hp XP-382 stroker 360 is visually identical and the big news for Superior Experimental engines in 2015.

Titan

Meanwhile, in another part of Texas, ECI has reorganized to accommodate recent growth, the upshot being the ECI name now denotes engine parts, and Titan is the name for assembled Experimental engines.

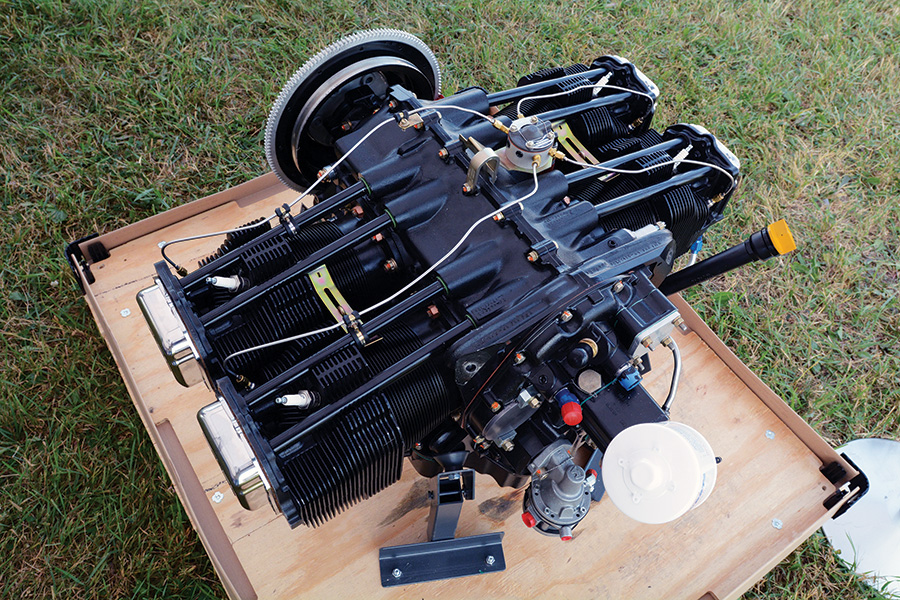

Titan says their best seller is this 190-hp XP-360. Almost as popular will be the 195-hp, 370-cube stroked version on sale in 2015. Adding a counterweighted crank and more compression makes it an X-371 at 205 hp.

Things are seemingly running at takeoff power at Titan. Bart LaLonde is now the general manager, having sold his well-regarded Aero Sport Power shop three years ago (and just now letting the cat out of the bag), while Kevin Eldredge is busy making a business case for all-new engine combinations.

The ECI name is now used for engine parts, such as these new electro-polished stainless steel valve covers, and the Titan name is used for assembled Experimental engines.

Titan is selling only complete engines-no kits-divided into F, X, and R series. The F engines are Titan factory remans, offered on an as-available basis, so you need to monitor their web site to catch these occasional deals. The X engines are the practical, daily-bread offerings most homebuilders are interested in, and they are built from all-new parts. The R engines are high-performance units also built with all new parts, but using Titan’s innovative, new, one-piece, lightweight, all-aluminum AX50 parallel-valve cylinder for 360/540s. You’ll also see carbon intakes and other goodies on some of these up-market engines. Eldridge reports rapid sales of the AX50 cylinders and gets animated when laying out the possible combinations they allow. We agree and are eager to see how the new cylinder holds up in real-world use.

Titan’s R-series engines are distinguished by their use of one-piece, all-aluminum AX50 cylinders, which are now in limited production. The cylinders save weight and make more power, but, as you guessed, cost considerably more.

Titan showed a weight-phobic 320LT at AirVenture, but the combination could not meet its weight and durability goals simultaneously and has been abandoned. However, the Swiss-cheesing and magnesium weight reduction knowledge has been judiciously applied to Titan’s popular 340 (a stroker version of the 320), which seems to be working out much better at 185 hp and just 245 lbs. It’s aimed at the backcountry Cub crowd.

In December 2015 Titan will offer a counterweighted crankshaft and a bump in compression to move their popular X-370 (a “big” 360) from 190 hp to 205 hp. The new configuration is called an X-371.

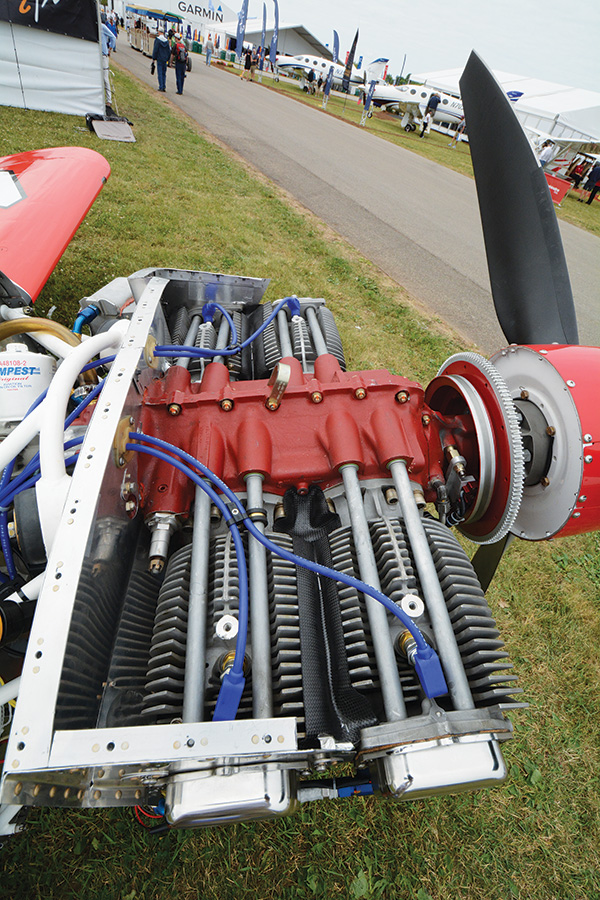

Another big step last December was Titan shipping their first new 540 six-cylinder to the delight of the RV-10 and fly-upside-down crowds. Like all current four-cylinder Titans, every six-banger 540 case boasts a forward propeller governor pad, so that’s now universal at Titan. The X-540 is available with parallel- and angle-valve cylinders, and both are rated up to 305 hp (we’d think the angle valve would have a higher rating, but Titan is seeming a bit coy here).

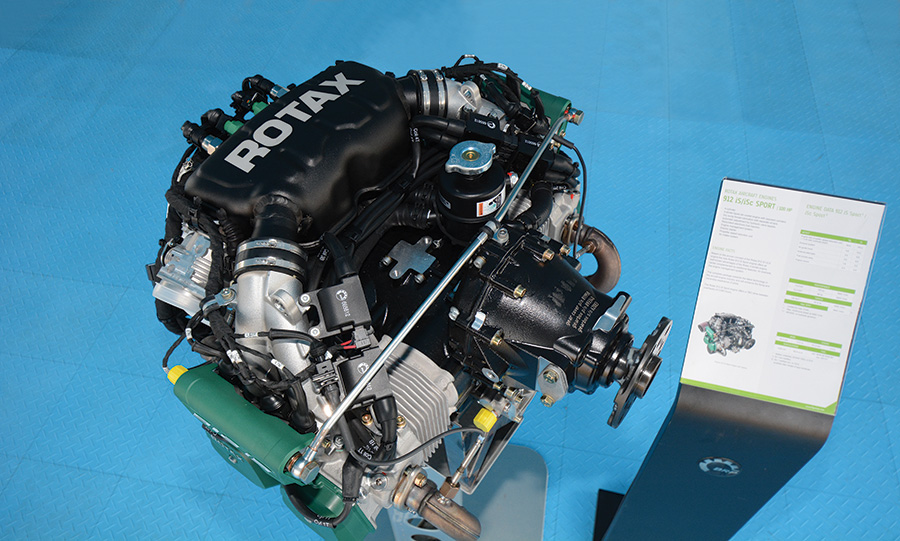

Rotax

Darling of the light-plane set, Rotax had been busy switching their popular 100-hp 912ULS from carburetion to fuel injection as the 912iS. The early 912iS lost torque compared to the carbureted 912ULS, so Rotax found a solution with a new intake manifold, air box, and software upgrade to arrive at the 912iS Sport in 2014. The Sport adds the missing torque, retains the same horsepower, and costs the same, so it is replacing the original 912iS. At press time Rotax was working on a retrofit scheme to update 912iS engines already in service to Sport specification. The remainder of the Rotax line remains unchanged except, as we went to press, pricing was reduced $500 on the out-going 912iS, the 912UL, and the 914UL turbo engines; a welcome development.

The new intake manifold and inlet layout is the visual giveaway on Rotax’s 912 iS Sport engine. It is replacing the 912 iS.

MW Fly

MW Fly, an Italian engine line, is slowly making inroads in North America. Demonstrated changes this year were in the engine management software, which now interfaces with TL Electronic Integra and Dynon SkyView systems to display engine information on those EFIS screens.

CAMit

Not truly new, but brought to our attention, is CAMit, an Australian firm with long ties to the Jabiru engine. CAMit has been developing Jabiru upgrade parts for some time and may open a North American outlet if a distributorship can be established. In the meantime they’ll respond to individual requests.

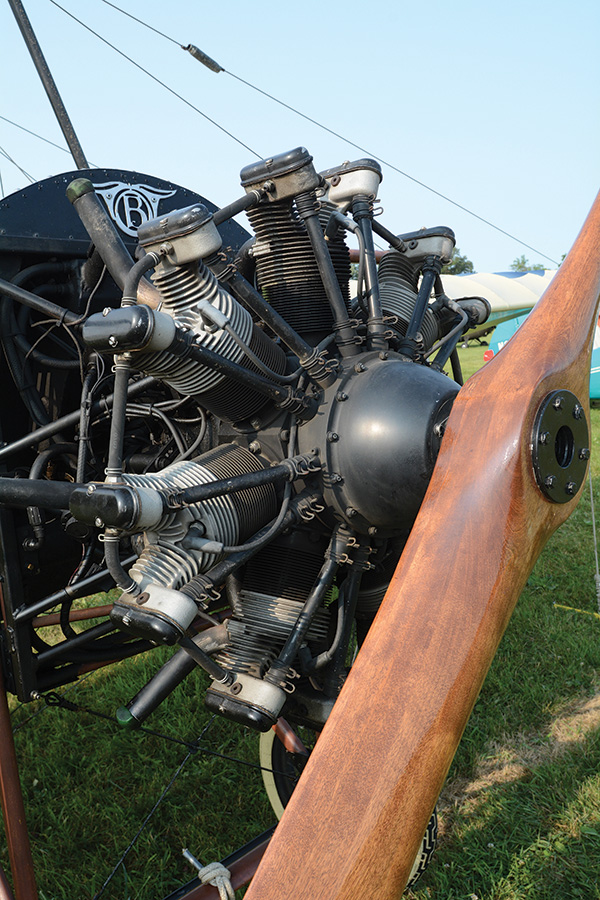

Rotec’s radials are the arty choice in light-plane power. Seven-cylinder R2800s like this one on a Bleriot XI replica are relatively common; deliveries of the 9-cylinder R3600 are now increasing.

The Custom Shops

There is another popular option for buying a new or rebuilt engine for your flying project: custom shops. These are the big rebuilders you’ve heard about-American, Aero Sport Power, Barrett, Ly-Con, etc.-that also build Experimental engines. They are dealers for the OEM and clone folks, plus they build their own Experimental engines from cores from either their stash or one you supply. Pricing between a custom engine from these shops and an off-the-shelf new unit from the manufacturers is a close thing these days as the manufacturers put the squeeze on the shops, but the custom shops can give you exactly the engine you want and, if you have a good core, they can definitely compete on price. The custom shops offer more services, too, such as dyno break-in ($1,000 well spent!) and cutting-edge options such as case O-ringing. They’re worth a look.

Conversion Engines: Newest of the New

Auto engine conversions are looking up in 2015. Several companies are offering new advances, and those who have graciously bowed out have been replaced with new companies.

AeroMomentum Aircraft Engines

One newcomer is AeroMomentum, offering two engines based on the proven Suzuki G series. The smaller 1.3-liter AM13 puts out a very respectable 100 hp, comparable in power and weight to the Rotax 912 and Continental O-200. The larger engine is the 1.5-liter AM15 with 117 hp. Similar in power to the Lycoming O-235, it’s lighter in weight.

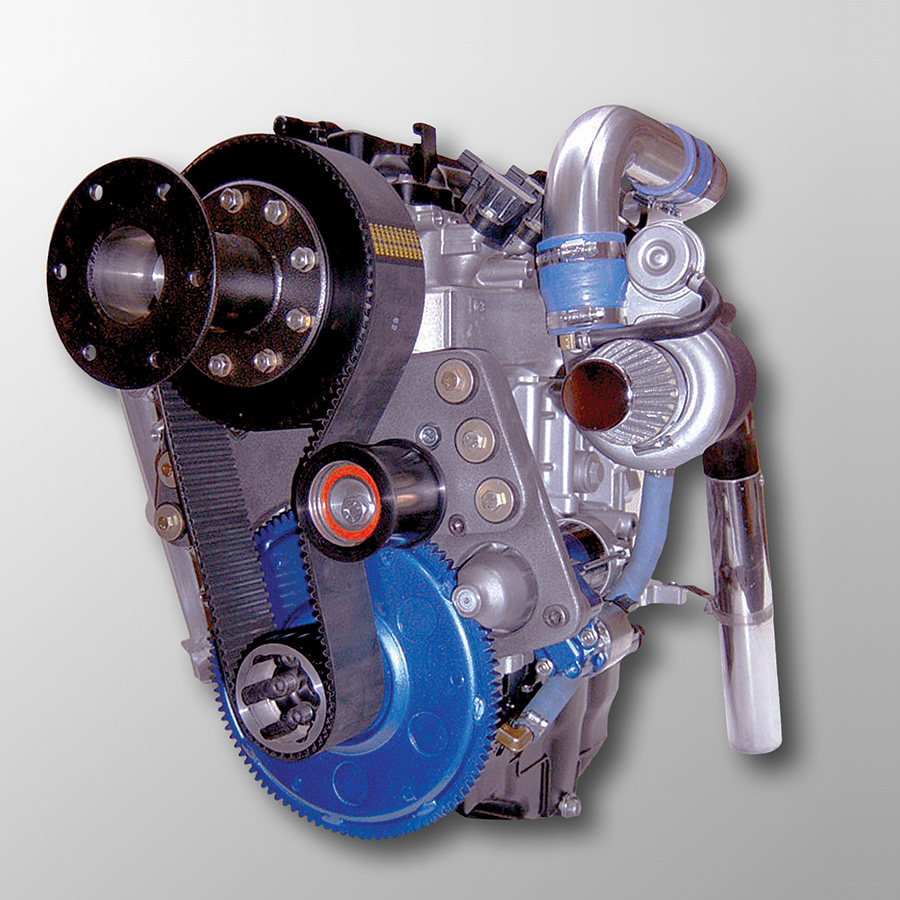

Both engines are built in upright or low-profile slanted versions. The uprights are found mostly in trikes and replica aircraft requiring a narrow engine package. The low-profile slanted version places the engine at 70 degrees from vertical to fit more conventional cowlings. The engine was designed to be mounted at an angle and does not affect reliability.

The propeller speed reduction unit (PSRU) uses a geared design with the same TBO as their engines. The only service is periodic oil changes-no belts or other expendables. The PSRU case is CNC machined from aerospace aluminum billet, and the forged gears and shafts are finished to AGMA aerospace standards. Coupling the engine to the gearbox is a German-made Guibo rubber dampening “donut” designed to last to TBO. The PSRU is designed for 4-cylinder engines up to 210 hp and utilizes oversized gears and bearings for extreme durability and reliability. The propeller shaft is hollow, allowing for mechanical propeller pitch adjustment. The hub is drilled for standard Rotax, high-power Rotax, and optional SAE 1 propeller bolt patterns.

Both the AM13 and AM15 are fully engineered by a team of graduate aerospace engineers. They started with a proven reliable base engine, then engineered robust, but lightweight, systems around it using CAD and CAE-like static and dynamic FEA analysis.

D-Motor

Going for maximum torque with minimum weight and complexity (only 35 moving parts), the new-design 4-cylinder, 4-stroke D-Motor uses large displacement, direct drive, and all the latest electronic controls to reportedly out-thrust and under-weigh the LSA competition. Built in Belgium, but assembled in the U.S., the D-Motor has been flying in Europe for two years and should complete ASTM certification by our press time. The $17,500 list price includes a very complete firewall-forward kit. The 4-cylinder is available now; a 6-cylinder should come online by AirVenture.

Firewall Forward Aero Engines

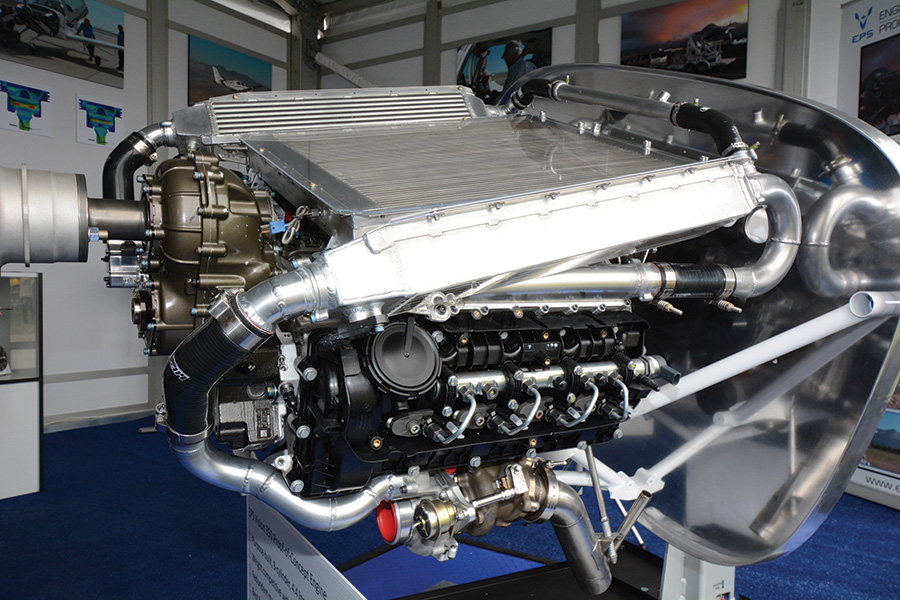

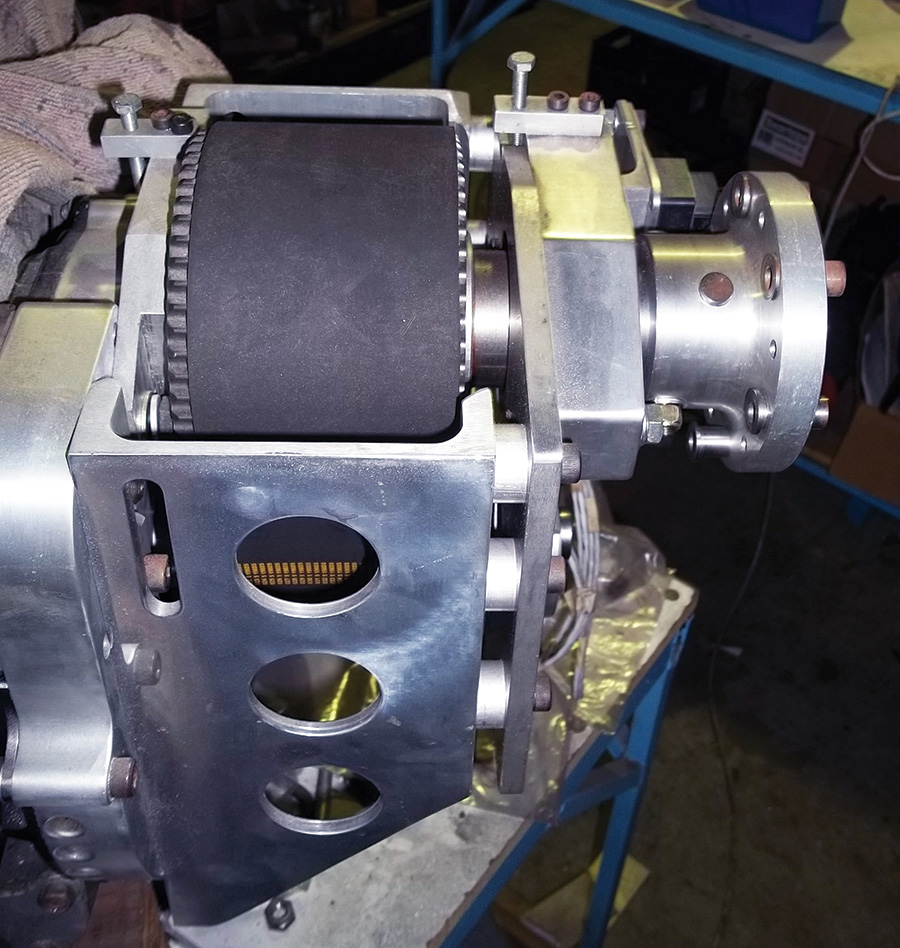

The Camdrive 500 helical-gear PSRU was designed by Firewall Forward Aero Engines in the mid-1990s when demand for high-output automotive V-8 conversions was growing. Firewall Forward examined every PSRU then available, addressed the shortcomings in each to develop an aluminum case with helical cut steel gears manufactured to tolerances of less than .0005 inch, with an idler gear to keep the prop in the “proper” direction of rotation. A custom bellhousing was designed to fit all GM LS series engines, right up to the LS9.

An integral two-stage oil pump provides lubrication to a set of precision oiling jets for each bearing and gear via passages drilled into the case halves. Notable features include two power takeoffs, one used for an optional prop governor and the second for a vacuum pump or standby alternator. The prop flange is easily changed to allow experimentation with various props, and forward engine mounting pads are cast into the sides of the bellhousing.

Installing the Camdrive 500 and bellhousing takes about an hour on GM LS engines. Dowels are provided to ensure precision alignment, and two bolts pass through the PSRU and bellhousing into the factory-provided bosses on the engine block. Recent improvements to the design allow up to 700+ horsepower. A custom designed fail-safe coupler connects the flywheel to the input shaft of the PSRU. Base price is roughly $21,700 and includes 2.18:1 final drive gears.

FlyCorvair.com

After 26 years of working with Corvair flight engines, and over 16 years actively selling his Corvair engine conversion manual and various conversion parts, William Wynne has recently released the most comprehensive version of his conversion manual to date. Close to 250 pages are printed with a wealth of information for anyone considering building, buying, or flying a Corvair flight engine.

The cover image for William Wynne’s new Corvair Conversion Manual, a 100-hp, 2.7L, air-cooled, direct-drive Corvair engine.

If one of your goals is to be the master of your airframe and engine, the Corvair is an excellent choice. While there are plenty of engine options for those wanting to checkbook engineer their homebuilt’s engine, Wynne’s efforts are aimed squarely at expanding the personal knowledge and skill set of each builder, and his manual goes a long way toward helping builders meet this goal.

In an era when more and more U.S. manufacturing jobs are being exported, and flagship companies such as Continental, Cirrus, and Glasair are being sold to China, Wynne prides himself that every part he sells for the conversion of the Corvair engine is made in the USA, as well as the core engine itself. About the only part needed for the Corvair engine conversion that’s no longer made in the USA is the distributor cap.

Hexadyne

First seen in 2001, the 60-hp Hexadyne P60 2-cylinder 4-stroke engine has been upgraded with proprietary computerized engine management. A clean-sheet design built in Salt Lake City, Utah with no auto parts, the P60 is a natural 2-stroke Rotax replacement and will re-debut at Sun ‘n Fun 2015.

Pegasus

An updated, lighter, stronger, two-cylinder version of the O-200 Continental, the Pegasus has enjoyed continuous development and goes on-sale at AirVenture 2015. It uses all U.S.-made parts including bespoke case halves, is a smooth runner, and will arrive as a sub-$3,000 kit for owner assembly.

PropDrives.com

Last year we mentioned Tracy Crook of Real World Solutions (RWS), maker of the planetary PSRU used on most airworthy Mazda rotary-powered aircraft, had retired. We also mentioned two highly qualified individuals were going to pick-up where he left off, but at the time of that writing, nothing had been formalized. Since then, they went into limited production, but have since passed the torch to me, Patrick Panzera. While I’ll be slow in ramping up, I have a great source of vendors and suppliers and all the tech-support I’ll ever need from Tracy.

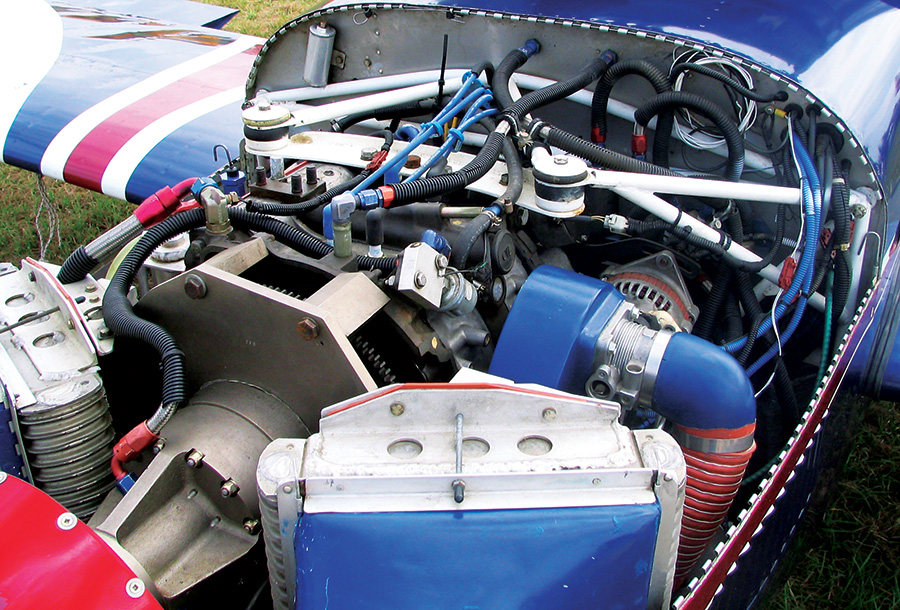

Among the wide range of auto conversions is Real World Solutions’ (now PropDrives.com) PSRU mounted to a three-rotor Mazda engine. This installation powers a Velocity RG.

RAM Performance, Ltd

RAM Performance is a leader in the technology and building of Subaru engines for automobile racing, marine, off-road, and everyday driving, and has been since 1984. Their goal is building the best engine possible at a competitive price. One claim to fame is that they are the first to not only offer multiport EFI on the little EA-81 Subaru, but also to offer it supercharged.

Offering a full line of aftermarket replacement parts in both the stock and high-performance (and custom) arenas, full support is available to the engine builder or repairman. While they don’t produce a PSRU, they work with several quality manufacturers to build the engine to fit your application.

Raven ReDrives

Raven ReDrives Inc. has successfully built proven, affordable Geo/Suzuki engine conversions for 19 years, and now they’ve added the Honda Jazz/Fit 1.5L VVT engine to their lineup.

Raven has pulled out all the stops to maximize power and reduce weight of their new Honda 1500 XVT (115 HP/140+ HP Turbo) packages. Trademarked as the STOL-Max, Raven’s emphasis with the Honda is the optimization of takeoff and climb power without sacrificing reliability or fuel economy at cruise-a best of both worlds approach.

By retaining as much of Honda’s proven stock automotive engine as possible-upright orientation, variable valve timing, main bearing girdle/windage tray, base intake manifold plenum, and structural engine mounting points-Raven hopes to maximize long-term reliability while minimizing costs. Maximum power and minimal weight come from Raven’s custom-tuned exhaust system, super-efficient upper intake manifold, full-flow coolant system, custom redrive (PSRU) ratio, redundant water pump/alternator belt drive with aluminum under-drive pulleys, and a lightweight starter.

Key to this package is Raven’s trademark ReDuction Drive. With integral torsional dampening upper prop hub, it eliminates rough idling and long-term engine/drive stress. Also included is the SDS (Simple Digital Systems) aftermarket ECU for custom ignition and engine fuel management. This flight-proven ECU package allows custom tuning by the owner.

Raven’s STOL-Max design approach maximizes the advantages of the Honda’s vertical configuration. A narrow cowling with lower drag, better visibility over the nose, and integral cooling airflow paths are some of the benefits. Even a custom propeller optimized for STOL performance is part of the complete engine package. Firewall forward packages are being developed now for the popular Zenith 650 and 750 airframes, along with a 140+ hp turbo upgrade with aftermarket forged low-compression pistons.

Revmaster Aviation

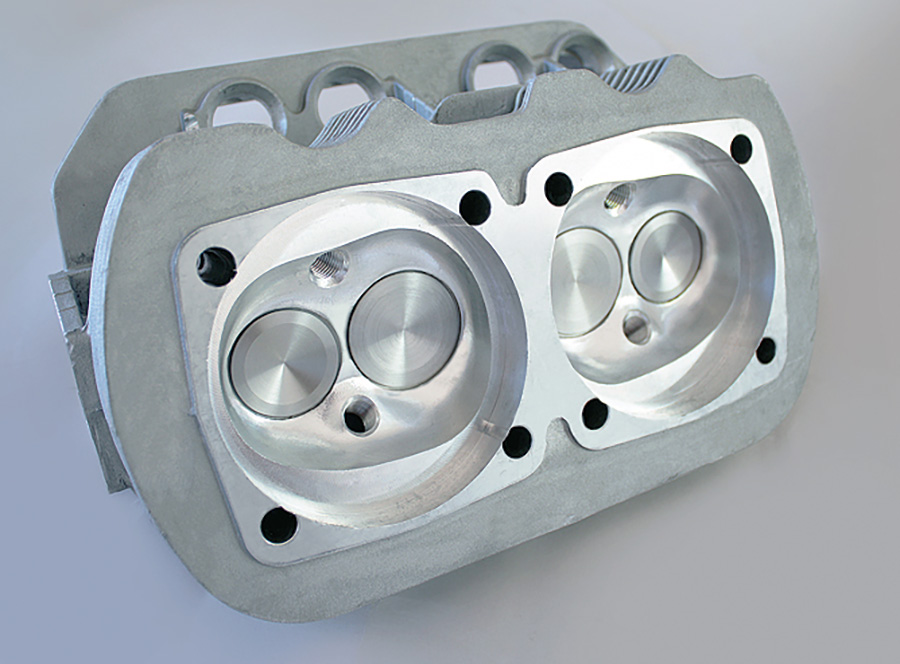

Since 2013, Revmaster has had great success offering their proprietary 049 cylinder head to the VW automotive aftermarket. In fact, the 049 has become a staple within the racing world, setting NHRA records and placing in the top three at the recently run Baja 1000.

Revmaster Aviation’s partners, Joe Horvath and Ralph Maloof, displaying the R2300 with the new Sensenich composite propeller.

Now the research and development from the racing world has translated to advancements for the 049 in its dual-spark-plug aviation format. Ruggedly built, the thick-wall casting was designed for large-displacement engines and features stainless steel 40mm intake and 35.5mm exhaust valves with chrome-moly retainers and hardened keepers. Digital flow analysis and CAD advanced the 049 head’s volumetric efficiency, while CNC machining on Haas five-axis equipment gives perfectly sized and located combustion chambers from cylinder to cylinder, along with optimized ports.

Power and efficiency is optimized mainly from unshrouding the valves and increasing airflow at all valve lifts-especially low lift where the valve is most present. “It’s a lot of extra work, but we feel it’s worth the extra expense in time and money.” said Mike Ballard, Revmaster’s racing director.

Other Revmaster news is they have begun testing Sensenich’s new ground-adjustable composite prop for VW applications, and the Thatcher CX5, mentioned in last year’s Engine Buyer’s Guide, has logged in excess of 100 trouble-free hours with the Revmaster R2300 2.3 liter engine.

VW Engine Centre

While no longer building or selling turnkey auto conversions, VW Engine Centre of Queensland, Australia offers a robust belt-reduction drive proven on a number of conversions, from the air-cooled VW through the Chevrolet LS1 V-8.

Also, VW Engine Centre’s owner, Ron Slender, offered this gem: “Although in many cases, an auto engine conversion is not necessarily cheaper to install, if it is done right, the savings on fuel, cost of replacement parts, maintenance, as well as TBO costs are a significant savings over a certified engine.”

VW Engine Centre belt-reduction drive on Volkswagen Type 4 engine, 125-hp with EFI, built for an electric variable-pitch propeller. All cogs are hard anodized.