Selecting the right type and weight of fabric to cover your airplane project can be confusing. Advice on the correct fabric is plentiful, varied and sometimes inaccurate. Years ago, aviation pioneers used a wide variety of fabrics on their aircraft and finally chose different types of linen and cotton. Grade A cotton, as it is referenced, became the standard fabric for use on most aircraft until the 1950s. However, cotton material was and remains susceptible to deterioration from sunlight and mildew. Polyester fabric was later developed and has become the fabric of choice for aircraft covering. Different styles and weights of polyester are available, and determining the correct weight is an important consideration. As you will see, the aircrafts mission, engine size, aircraft speed and other factors influence the fabric weight you need to use.

A Bit More History

The early pioneers in aviation realized that a better alternative to muslin and cotton fabric needed to be developed. Cotton fabric must be coated with nitrate dope-a flammable chemical. Nylon was tested only to find that it stretches too easily, and after being shrunk returns to its original state.

Polyester material was developed during the 1940s in England. DuPont obtained the rights to manufacture this product in the United States under the trade name Dacron. DuPont published information on shrinking this material by applying heat, and Colonel Daniel Cooper began testing polyester fabric for aircraft applications. In 1958, Cooper termed his new material Ceconite and began selling it to cover aircraft. By this time butyrate dope had been developed and was being used as a coating.

During the early 1960s, Ray Stits developed a fabric covering system using polyester fabric, which used chemicals other than nitrate and butyrate dope. He wanted a system that would not support combustion and that would not continue to shrink fabric over time. (Nitrate and butyrate dopes will continue to shrink both cotton and polyester fabrics through the years. This shrinkage is not critical if the fabric is properly applied.) The Stits Poly-Fiber covering system was introduced in 1965 and rapidly found widespread use.

Fabric Options

You have limited choices regarding fabric. Polyester is the main type available today, as Grade A cotton has all but faded away. To my knowledge, there is no Grade A fabric available today that meets FAA requirements. If you find Grade A fabric, you must ensure it meets the proper specifications listed in the Technical Service Order C-15d.

All types of polyester are basically the same regardless of their name. Both Poly-Fiber and Ceconite contract with a mill to have their fabrics loomed to the same specifications. Cooper Superflite is similar. Polyester fabric for aircraft will heat shrink approximately 10 to 12%, which allows us to apply the fabric loosely to the aircraft structure and then shrink it using a properly calibrated household iron. This provides the aerodynamic tension needed for flight.

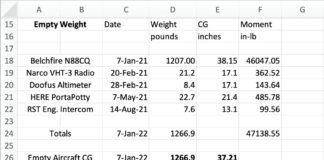

Fabrics are also identified by their weight, which is measured in ounces per square yard. Light weight fabric weighs 1.7 ounces per square yard, medium 2.7 ounces, and heavy 3.4 ounces. The thread count of each fabric varies among types with the light weight fabric having a higher thread count than heavy weight; the light weight fabric will appear smoother. Strength of the fabric also varies with weight. Light weight fabric has a lower breaking strength than heavier weights (see Chart 1).

Fabrics are certified by the FAA for use on production aircraft through Technical Service Orders (TSO), which apply to all aircraft fabrics including Grade A cotton. Fabrics are certified for use on production airplanes and should have a Parts Manufacturing Authorization (PMA) stamp, which specifies weight and type. Certified fabric has been inspected for flaws prior to being shipped for use on aircraft; non-certified fabric has not. If you are covering a production airplane, you must use only certified fabric. Ultralights and Experimental aircraft may use non-certified, but it is not recommended. Covering systems must possess a Supplemental Type Certificate (STC) to be used as replacement fabric covering systems on production aircraft. The inspected and certified fabric mentioned is part of this STC process. If you do not see PMA stamps on the fabric you purchase, do not use it on a production airplane.

The PMA stamp appears at 3-foot intervals on certified fabrics. The ink is a special type that will not bleed through the final coats of paint on your airplane. A point to remember: Do not use ink pens to mark on fabric while re-covering your aircraft; use only pencils. Most inks (except the one used for the stamp) will bleed through the final color coats.

Certified fabrics are regularly tested to comply with FAA requirements. The U.S. Testing Company, an independent testing entity, conducts the tests, which include bursting strength, tension and tear strength. The results are published.

Down to the Requirements

With all of this in mind, what factors influence selection of fabric for your covering project? One of the major problems associated with fabric covering has to do with the fabric flexing when the airplane is flying. Flexing problems are most prevalent in the prop-wash area of an airplane. Excessive flexing cracks the coatings that have been applied to the fabric, which results in rapid deterioration of the entire covering, and causes premature repairs or even a complete re-covering of the airplane. Light weight fabrics are more prone to this problem than heavier fabrics, which damp the flexing motion simply due to their heft. A contributing problem results from large spaces between structural members such as wingribs, which cause more flexing and bending of the fabric. Add to this a high horsepower engine and a propeller that is beating the area, and the problem becomes even more acute.

Another problem is on gear legs, where the engine exhaust may be blasting directly on the area. Again, light weight fabrics are more susceptible to damage here. The underside of a fuselage is another area where problems can occur due to rocks and other debris being thrown against the surface.

So lets get to the point. What fabric should you use? First of all, we have determined that you should use polyester fabric. Even if you can find Grade A cotton, it may not meet FAA requirements, and it is a more difficult system to apply.

Weighty Matter

What about proper weights and styles? On light aircraft with a wing loading of less than 9 pounds per square foot with never-exceed speeds of less than 160 mph, you can use light weight (1.7 ounces/square yard) fabric. The aircraft found in this category are ultralights, very light aircraft, gliders, most Light Sport Aircraft and kit aircraft with engines of less than 65 horsepower. It should be noted that both Poly-Fiber and Ceconite light weight fabric is uncertified, which means it can only be used for Experimental aircraft, not for production airplanes-with one exception. If you were covering a plywood surface on a production airplane, you would be able to legally use the light weight uncertified fabric.

For aircraft not in the above category, medium weight fabric (2.7 ounces/square yard) is considered the standard. In other words, medium weight fabric may be used for all normal service aircraft including antiques, classics, kit aircraft and all contemporary designs that anticipate normal airport operations. Heavy weight (3.4 ounces/square yard) fabric is recommended for more severe operating conditions and for high-wing-loading aircraft. The polyester filaments in heavy fabric are larger and the strength is greater, resulting in excellent resistance to damage and to tearing. Heavy weight should be used where a tough, durable, high-tension fabric is needed, including aerobatic planes, ag planes, warbirds and larger aircraft. (Chart 2 shows proper selection.)

Poly-Fiber fabrics are identified as light uncertified (1.7 ounce), medium (2.7 ounce), and heavy duty (3.4 ounce). Ceconite fabrics have uncertified light (1.7 ounce), Ceconite 102 (2.6 ounce) and Ceconite 101 (3.4 ounce). All of the fabrics are 70 inches wide with the exception of the light weight fabric, which is 60 inches wide. Fabrics are sold by the running yard, so that you can calculate the amount needed for your project. Both the Poly-Fiber covering manual and the Ceconite manual contain yardage estimates for most popular homebuilt aircraft.

Let’s Go to the Tape

Any weight of tape may be used with any style of fabric. Most experienced builders use light weight tapes on all weights of fabric. A light weight tape is simply light weight fabric that has been cut into different widths of tape, typically 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 inches wide. Medium weight tapes are cut from medium weight fabric. Do not use cotton tapes on polyester fabric. Do not use Ceconite tapes on Poly-Fiber fabric or vice versa. Doing so will void the STC of each system. Ceconite and Poly-Fiber tapes will work on the other fabric, but it is not legal to use them on production aircraft. We will discuss more about fabric tapes later in the series.

All types of fabric will deteriorate in direct sunlight unless properly protected. There is no so-called “lifetime” fabric. Polyester fabric is not as susceptible to this problem as cotton; however, if bare polyester fabric is left in direct sunlight for 12 months it will lose over 85% of its strength. Cotton fabric exposed to the same sunlight for the same period will deteriorate almost completely. Polyester fabric is protected from UV rays with chemical coatings containing aluminum pigment. Application of the recommended number of aluminum coats will provide adequate protection for years. (We will discuss how to do this later.) A properly applied covering system should have a 15-year life even if the plane is left outside. The same system on a hangared airplane should result in more than 20 years of service.

After selecting the proper weight of fabric for your covering project, how you attach it to the structure is equally important, especially achieving the correct tension. Next time well discuss how to apply the fabric and the proper way to shrink it for final tautness.