The story of the Just Aircraft Highlander begins with Gary Schmitt. He was drawn to a small two-seat tandem bush plane designed by Troy Woodland of Just Aircraft at AirVenture 2003. Every time he passed Woodland’s display, Schmitt “hinted” that the ideal bush plane should have side-by-side seating. Eventually Woodland relented and offered to build Schmitt the side-by-side bush plane he envisioned, if Schmitt would fund the development.

The story of the Just Aircraft Highlander begins with Gary Schmitt. He was drawn to a small two-seat tandem bush plane designed by Troy Woodland of Just Aircraft at AirVenture 2003. Every time he passed Woodland’s display, Schmitt “hinted” that the ideal bush plane should have side-by-side seating. Eventually Woodland relented and offered to build Schmitt the side-by-side bush plane he envisioned, if Schmitt would fund the development.

Schmitt quickly agreed, admitting that he was naïve regarding what went into the development of a new aircraft. With the airplane finished, Schmitt soon found the price tag for his custom-designed and -built bush plane was a bit higher than expected. During the ensuing negotiations Woodland and Schmitt realized they had the same business and design goals, and they became partners in Just Aircraft.

Success came readily, and when production picked up, the owners searched for a larger manufacturing facility. By chance, Schmitt located a closed factory in Walhalla, South Carolina. So, in 2004, Woodland and a handful of production workers moved the tooling, jigs and inventory from Idaho to South Carolina.

When I first saw the Highlander at a South Carolina fly-in, it towered over a gaggle of Cubs, standing tall on its 29x13x6-inch Alaskan Bushwheels. The crowd it drew was a mix of people looking for a fun LSA to use for Sunday flying, hard-core camping types and everything in between. The Highlander pilot was besieged with a thousand inquiries from the admiring crowd: How much will it haul? What’s the empty weight? Does it qualify as an LSA? What are the cruise and stall speeds? How long does it take to build? What engine is in it? Look at those tires! How big are they? How much does it cost to build? In short, the usual questions.

From There to Here

Not being a professional test pilot by trade, I’m allowed to get excited about aircraft. And that excitement—along with serendipity in getting this assignment—led me to the seat of a rocking chair in front of the Just Aircraft factory. With me was aircraft designer and partner Woodland, and after some storytelling we got down to work. Woodland said Schmitt was on the way over with the demo plane; he suggested that we fly first and then tour the factory.

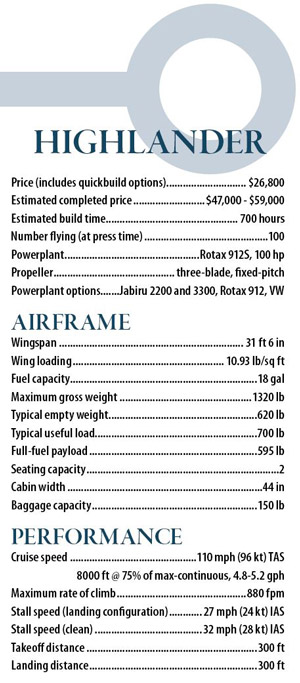

“I like bush planes,” Woodland said as he began explaining his design philosophy. “But I don’t like planes that break in the bush. Walking out is not fun. Everyone here in the States thinks you need a 200-horsepower Super Cub, but you don’t.” Woodland added that because Europeans understand light aircraft, his first design was for export. Only when the cost of fuel went up and Light Sport Aircraft regulations were in place in the U.S. did Americans begin to appreciate what light aircraft can do. “My goal, and I think I have achieved it, was to build a rugged bush plane that will not break in the back country,” Woodland said. “Although the Highlander has a low empty weight, 615 pounds, it is extremely strong where it needs to be. Less weight means less stress when bouncing over rocks, even at the 1320-pound gross weight.” With that Woodland walked inside and asked the office manager to move her car, because Schmitt and Steve Collins were on the way.

I looked around trying to figure out what that was all about. Woodland pointed over to the edge of the parking lot to a cut in the trees where the company runway was and said Schmitt would taxi into the parking lot after landing. Huh? There is no runway over there.

As I walked over I saw what he was talking about, but surely that couldn’t be a runway! Heck, I’m not sure I would even want to drive my father’s old Farmall H tractor across it. A few minutes later, we heard Schmitt circling overhead. As gracefully as you please, the gorgeous black Highlander landed on the hill and taxied to the parking lot. Not 5 minutes later, Collins taxied his white-over-black Highlander in.

Nice Touches

Climbing into the factory demonstrator with Schmitt, I noticed the headsets hanging overhead from a small hook sticking out of a tubing weldment. (The hook was designed so it will not impale someone in the event of an accident.) This attention to detail was impressive. “How many airplanes have you been in with no place to put your headsets?” Schmitt asked. “We solved that problem.”

Preflight completed, Schmitt pointed the Highlander across the parking lot—not a big one. My pickup would have a problem making a full circle in the area where the planes were parked. He added full power, and the Highlander leapt off the cliff. Normally I count how many seconds until airborne, but this time I counted bounces. Boing, boing, boing. I was waiting for the fourth bounce, but it never came. Not only were we flying, but we were climbing—strongly. I saw close to 1800 fpm at a mid-40s mph, thanks to the turbocharged 115-hp Rotax 914. (The factory assured me that number was correct.) Ah, the beauty of a light airframe and a strong engine.

As promised, the Highlander is a no-holds-barred bush plane. The flight controls are not light, nor are they heavy. I would say they are just right for this aircraft, stiffening at the 105-mph cruise (110 mph with the smaller tires) and giving the right amount of feel in the landing configuration. At one point Schmitt pointed out that I was holding the stick with my fingertips.

Woodland purposely designed the aircraft without differential ailerons, so the use of more rudder than most pilots are accustomed to is required. His logic was simple: When flying in the bush, there might be a time when someone needs all the aileron deflection he can get to keep a wingtip out of the dirt. Using a little rudder is much preferable to walking out of the bush. With all that rudder control and just the right amount of wing dihedral, it is easy to fly hands-off while holding the heading with the rudder.

Short takeoff and landing (STOL) is an understatement when characterizing the Highlander. Woodland mentioned that he was in the process of clearing some trees for a runway at his home. When asked how long it would be, he said, “About 250 feet.” Silly me, I was thinking in terms of several hundreds of feet.

Some Left Seat Time

We dropped in on Billy and Vic Payne, two brothers who built a bright orange Highlander with a tuned exhaust and radical paint job. Billy is an LSA instructor, so he directed me to the left seat, while he jumped in the right. With the 100-hp Rotax 912S up and running, oil and water temps in the green and a quick ignition check completed, we taxied to the runway. We could easily have taken off from the taxiway and been flying before we passed four hangars, but proper aviation decorum prevailed.

As we climbed past some small peaks, I performed steep turns and quickly realized that the visibility in the Highlander was outstanding. The clear skylight allowed me to scan for other airplanes when in a tight turn. Don’t get me wrong, the Highlander will never be mistaken for a fighter with a bubble canopy, but as high-wingers go, the visibility was great.

After skimming the mountain ridges, we headed back for some landings. This is where everything should come together. But the first approach didn’t feel right, even though we had plenty of runway, so a go-around was in order. With full power and flaps, we climbed at better than the published rate of 880 fpm. The 100-hp engine proved to be more than an adequate match for the airframe.

What didn’t feel right on my first approach was the low speed required. Airplanes with high approach and landing speeds never bothered me. However, slowing to 40 mph didn’t sit well. With the airplane above its stall speed (27 mph with 40° of flaps and 32 mph without) the control feel was solid with no tendency to over control. The go-around was simply a matter of prudence.

Lined up for a second approach, full flaps, and slowed to 40 mph, all was right in the world. Over the fence I started to round out. As the speed bled off I realized I was a touch high but no worries; this is a bush plane after all. When the stall happened, it broke straight ahead, no wing drop, nothing. Those monster tires coupled with the bungee-cord suspension absorbed the landing as if I had just rolled it on, and the large rudder works well at the low airspeeds this plane is capable of. While it is easy to overdo the rudder at cruise speeds, down at the speeds where most pilots taxi, the Highlander is still flying and the rudder authority feels perfect. Once the tailwheel is on the ground, there is little or no tendency to over control.

With dual rudder pedals and brakes standard, this would be an easy aircraft for a lifetime trigear pilot to master. Given the low landing speeds, the chance of a ground loop is greatly reduced. Converting to a trigear version is possible at any time for those who insist on having the little wheel up front.

Building a Highlander

Visiting the factory offered me the opportunity to see the kit materials and construction techniques up close. The wing uses routed wood ribs with cap strips bonded to tubular aluminum spars and is cross-braced with smaller tubes. This design makes for a light and strong structure. Woodland demonstrated the company’s wing jig, commenting that customers are strongly encouraged to buy the quickbuild wing option to guarantee a straight and well-built structure.

Woodland explained his desire to minimize the parts count on his aircraft designs. He justifies using tubing for the spars, because they are easy to inspect, relatively inexpensive to purchase, light and strong. Those last three words are used frequently as he discusses aircraft design. The production tooling for the welded parts is similar to what you would see at any aircraft manufacturer. Large steel fuselage jigs, and smaller horizontal and elevator jigs are laid out in a logical sequence. Woodland felt that in some cases non-AN hardware might provide the required strength for less weight and cost. However, customers prefer AN hardware, so that’s what is included in the kit.

According to Woodland, most builders complete their Highlanders in 600 to 700 hours with an average investment of about $60,000. There are just more than 100 aircraft flying and 85 kits currently under construction around the world, a good number for a company whose advertising is word of mouth and via customer videos posted on YouTube.

Part of the reason for the high project completion rate are the builder manuals and the builder-assist program. The manuals include both easy-to-follow instructions and pictures. The builder-assist program is not like some others. There will not be an employee standing by to hand you tools, as a nurse does during surgery. However, all of the production tooling, specialty tools, paint booth, etc. are at the builder’s disposal, along with the expertise of the factory employees.

It’s the Small Things

Just Aircraft’s attention to detail was evident, from the foldable wings to the aforementioned headset hooks to the adjustable seats. Woodland explained that initially he planned on including adjustable rudder pedals but realized that people with long legs also have long arms. Just as in some production airplanes, then, you can slide the seat aft, climb in and then slide it forward. This provides enough room to accommodate the short and the tall. The seat backs also tilt forward, allowing easy access to the ample luggage compartment. The tubing structure is exposed in the baggage compartment, which provides numerous locations for securing gear, but Just Aircraft went one step further and added tiedown rings.

While many aircraft advertise wide cabins, that measurement is usually taken at the elbows. The 44-inch-wide cabin of the Highlander is measured at the shoulder, where it is a true 44 inches across. Never once did I feel cramped while flying, regardless of the size of each of the three pilots I flew with. The clear doors hinge at the top, and can be opened in flight. However, if your passengers are uncomfortable flying this way, you have the option of flying with only the windows open.

Folding the wings is a simple affair. Make sure the flaps are up, remove the aft turtle deck, remove the pin holding the front spar in place, and then swing the wings back. The only tool required is a screwdriver for removing the turtle deck. No flight controls are disconnected when swinging the wings, and they will not remain unfolded without the pin in place; thus, there is little chance of taking off without the wings properly secured.

After flying around the hills of the Carolinas and northeast Georgia, landing on remote spots that served alternately as mountain goat grazing land and Highlander runways, what did I think of the Just Aircraft Highlander? On the ride home from the factory, I called a friend with a nice J-3 Cub and strongly suggested that he sell it and buy a Highlander kit.

For more information, call 864-718-0320 or visit www.justaircraft.com.

I am interested to Glenmore. How w would I place an order.

@Wallace Aunan

You can see more at http://www.wildatlanticaircraft.com

Am happy to direct you if you contact me through the website.above

Gerry