There’s more to Kansas than wheat fields. In the south-central part of the state are massive grasslands, including the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve. Wichita, in south-central Kansas, is home to factories for certificated airplanes such as Beech, Cessna and Learjet. And northeast of the city, Wichita Gliderport is the home base for the Belite, an FAR Part 103-legal ultralight.

Why are we talking about the Belite, you might wonder. Because you can build this ultralight as a kit. And if you’ve had your medical certificate denied or revoked, you won’t qualify as a Sport Pilot or be able to fly Light Sport Aircraft, so Part 103 is your last legal chance to commit solo aviation.

Let’s Talk About Fun

I recall, maybe 30 years ago at Arlington, Washington, watching the ultralights fly. There were a half dozen ultralight pilots sitting around, enjoying each other’s company and talking airplanes. Every now and then, one of the group would break away, get his plane out of the hangar, preflight it and then do three or four patterns before putting the plane away again. I was there to fly the much more macho Glasair I RG, but I had a couple of observations. At first, droning around the pattern and calling that flying seemed dumb. And yet, the ultralighters appeared to be having a truly great time that day.

Flash forward 30 years to Kansas, where I’m about to have that first observation turned upside-down, and where James Wiebe is the proprietor of Belite, both the airframer and the electroniker. Tired of running his own high-tech company, he developed a line of lightweight instruments and now sells the Belite. Wiebe bought the Kitfox Lite assets from somebody who bought the assets at a bankruptcy court, including hard tooling for welding the fuselages and assembling the flaperons. He also bought a completed Kitfox Lite that, after being stripped of non-essentials, weighed 294 pounds, including a 95-pound engine. That became the prototype of the Belite.

Now Wiebe’s challenge, which he relishes, is to offer the best flying experience he can for the best price while facing the stiff limitations of Part 103. That task should not be underestimated. Reducing weight and cost at the same time is hard enough, but to improve handling qualities simultaneously is a heady promise.

Wiebe believes the last checklist item has been accomplished. “I thoroughly enjoy flying it,” he said, and that is obvious when you watch him. Meanwhile, over in the next hangar, his LSA is for sale, rarely flown. The Belite’s mission statement? To be a “real airplane” experience ultralight-like low cost; to be a pure flying experience that doesn’t need any excuses.

Airframe, Weight and Stall Speed

The airframe that Wiebe sells is a derivative of the old Kitfox Lite—same aerodynamics and much the same structure—itself related to the two-seat full size Kitfox. The proportions are much the same, the tail shape is much the same, both wings have Junkers-style flaperons, both have folding wings, and the severely undercambered airfoils, reminiscent of pre-WW-I airfoils, are the same Riblett airfoil.

But for Part 103, the two most daunting challenges are weight and stall speed. Wiebe took aggressive measures to address both.

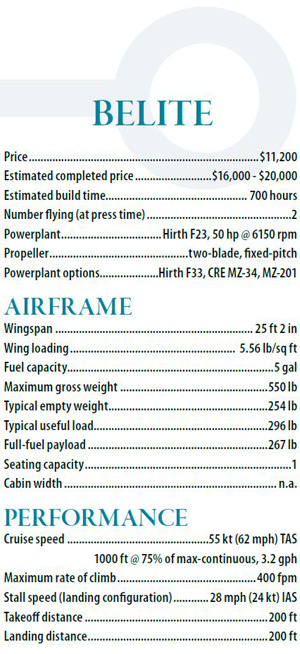

On the weight front, there are two approaches—lighten the structure and get credits. On the structural front, there are weight-saving details such as mountain-bike brakes (similar speeds and weight, easy to adjust) and a 125mm Razor scooter tailwheel costing $9. Plus, the Belite can be ordered with a number of options to further reduce weight. These include carbon-fiber mainspars instead of aluminum (saving 12 pounds for $2200). The fuselage can be welded from more expensive steel tubing with thinner walls (4.5 pounds, $800). Standard wingribs are now aluminum—they weigh no more than carbon fiber—instead of wood, saving 2 pounds. For a homebuilt version of the Belite, you’ll be starting these cost computations at just $11,200 for an airframe/wing kit using fully welded components; weld it yourself and save $1200.

Weight credits are written into the rules. For a ballistic parachute, you get a 24-pound credit, regardless of how much the parachute weighs. The Belite uses a Second Chantz parachute, deployed with compressed air rather than a rocket. It weighs only 15 pounds, however, allowing 9 pounds of other options to be added (about $2300).

The other big challenge is stall speed. The Belite flaperons lower the stall speed to within the legal range, but for handling qualities reasons, Wiebe suggests that newbies not use more than 10°. “If I had my druthers, I’d eliminate flaps,” he said. Vortex generators were added to the Belite I flew to reduce stall speed, and the calculated stall speed is 26.5 mph. (Advisory Circular AC103-7 details the ins and outs of Part 103 compliance, with many surprises. For example, you can rent an “ultralight vehicle” to another person.)

Three Belites, No Waiting

But there are more rules. Part 103 limits you to a top speed in level flight of 55 knots, but it is legal to comply with that regulation by putting a stop in the throttle linkage as long as the linkage cannot be removed in flight. This also offers the ability to legally use more horsepower at higher density altitude by (re)moving the throttle stop. You still have to make weight with your engine, though.

Speaking of engines, Wiebe sells three engines for the Belite: The 45-horsepower Compact Radial (that’s the name of the manufacturer) MZ-201, the 28-hp Hirth F33 and the 50-hp Hirth F23, derated to 38 hp. Under investigation is a four-stroke engine. But here’s the kicker—you can always build the Belite as an Experimental, use all 50 hp, and get a screaming rate of climb. There’s too much drag for a big engine to make much speed difference, but short takeoff and sparkling climb are more fun.

There are three models of Belite, varying only slightly. The basic airframe is called the 254, named after the weight limit of Part 103. If you want to install the 50-hp Hirth F23, which weighs 30 pounds more than the 28-hp F33, you need a lighter airframe to make weight, and that airplane is called the SuperLite. The tricycle-gear airplane is called the Trike, but it can’t take the big engine, either. If you want to fly the Belite as an Experimental/Amateur-Built, the maximum empty weight is 300 pounds. To put that in perspective, that’s the weight of 50 gallons of fuel. How many airplanes carry that much or more? Maximum gross weight for all models is 550 pounds. A 220-pounder could still fly the Experimental version with the 5-gallon fuel tank full.

Three to a Hangar

The hangar this day holds three Belites, several gliders, two towplanes and some ultralights. Ultralights have evolved tremendously since the early days, but Wiebe points out that of the three elderly ultralights, one is disassembled and one is for sale. Supposedly, the handling qualities and limitations of the early machines are such that the owners are no longer interested in flying them. Wiebe feels strongly that bringing the Belite forward as a “real airplane” will overcome these limitations and lead more pilots to continue flying after the newness has worn off.

We pulled the trigear Belite, just sold to a customer, out for a closer inspection. It has a rolled household enamel paint job that is quick and inexpensive to apply, though the finish won’t win awards. The trike is unsteady on its feet with wings folded, so one wing is extended while pushing it around. Folding the wings is incredibly simple—a push-pin with safety clip at each front spar and the same for the flaperons hookups. Short of hydraulic wing fold on a Navy fighter, it doesn’t come any faster or easier.

Wiebe then pulled out the SuperLite demo plane and, after a preflight, performed the starting ritual. Elements to rope-starting this engine include chocks for the right wheel, the choke on the throttle quadrant (it looks just like a mixture control), a can of ether to spray in the carburetors and a big bowl of Wheaties for breakfast. It was a workout, but eventually the engine started and all was right with the world, one that Wiebe says really should have electric starters.

A quick test flight revealed a slipping drive belt. Normally, the slippage goes away as the belt warms up, but not this time. Re-tensioning the belt was an easy job, but required two people.

In the Air

For my flight, the instrumentation was augmented with a combination CHT/EGT gauge and an analog airspeed indicator. Dead center in the instrument panel was a cup holder, just like the bizjets have but more usefully located, and doubling (when filled) as both a slip/skid indicator and a turbulence quantifier. After Wiebe performed another quick test flight, it was my turn.

The Belite is a comfortable airplane with plenty of leg- and headroom, and effectively unlimited shoulder room—unless you put in the door and window for winter flying. With the engine started by the faithful ground crew (Wiebe), I taxied to the far end of the gliderport. There wasn’t much to do in terms of a runup or checklist and, in fact, the Belite is that nirvana of the fun flier, an airplane with no pre-landing checklist.

The wheels on this Belite are larger (and heavier) than stock, but I wouldn’t want to have been on any smaller ones and navigated in the grass, smooth as it was. At the end of the runway, flaps to 10, check for traffic, and throttle in.

Boy, I wish I’d had earplugs, because the little Hirth engine screamed. Soon enough we were off the ground with an adequate climb, but throughout the flight I was conscious of the auditory price I’d pay for full power.

No surprise, this first flight generated considerable sensory input. The view, the noise, the wallowy air, the occasional wind blast on your shoulder—there was a lot going on. But it was clear that just a few patterns would quickly bring the sensory overload down into the top of the thoroughly enjoyable range.

Breezes Preferable

Wiebe prefers having people make their first flight with a breeze to reduce takeoff and landing roll, and winds were 10 mph, right down the runway. Recommended maximum wind is 12 knots due to taxiing limitations, but the highly proficient Wiebe has flown in a 22-knot wind.

The first takeoff was easy. No surprise, controls are light, and though I thought I had a mild pitch bobble on takeoff, they didn’t see it. Before flight, there was noticeable friction in the ailerons, and I was prepared for the possible effect, but it didn’t seem obvious in the air. In fact, the controls felt well harmonized. (Two other Belites on the field had much less control friction on the ground.)

What’s in the Box

The standard kit includes a wing kit with aluminum spars and aluminum ribs, steel fuselage, carbon-fiber firewall, steel spring main landing gear, steel leaf rear spring, seat belt and shoulder harness, Lexan windshield, fabric, wheels, tires, tubes, etc. This is a complete kit, firewall back. You only need to add engine, engine mount, propeller, fuel tank, instrument panel, paint, glue and miscellaneous. Total airframe price is $11,200. Tricycle gear is $800 extra. Engine and prop are $3777 to $5655.

—E.W.

With a wind of 10 mph on the surface and more upstairs, the Belite was pushed around as you would expect. Mindful of not knowing the local area, and not being able to tell a gliderport from any neighboring field, I stayed in the pattern. Upwind, the ground speed was slow, but turning downwind was good for a great burst of speed.

In the pattern, the turns were easy, and the standard low-speed airplane techniques of using both stick and rudder worked well, even on the first turn. If you have ever flown an airplane that liked rudder in normal usage, you will have no problems here. Slip/skid indication comes from the blast of air on your shoulder, and you will use rudder to keep your shoulders warm. Interestingly, I had no coordination problems in turns, only when flying straight. A few pitch-pointing tasks showed good pitch handling, and a maximum effort roll from 45° left to right showed an adequate roll rate.

Spot On, First Time

For the first landing, I reduced power to a gentle descent and used power to give me the glidepath I wanted at 50 mph indicated in the wallowing air. In a real airplane, that’s called cheating. This got me down to right above the grass, less than a foot, and I eased off the rest of the power. The Belite touched down immediately with only a mild bump. The grass promptly dissipated all flying speed.

I recalled a fly-in years ago with a spot-landing contest. The ultralights would fly along the runway at 6 inches until they reached the line and then chop power, touching down immediately. Their scores were measured in inches.

It was too soon to quit, so I pushed the little throttle lever forward for more engine shriek, and away we went. I did a few more enjoyable laps and then came down for the second landing, as satisfying as the first. I aimed for the midpoint of the runway, hit my spot and was immediately slowed. With a little practice, you could land on any part of the runway you wanted, as long as you knew that you had enough power to perform a go-around over any obstacles.

Brakes, who needs ’em? I used them only for a sharp turnaround on the grass runway, but I may have dragged them along the way, for the heel brakes are right under the rudder pedals, not offset like in the old taildraggers. The upside is that you don’t have to take your feet off the rudders (almost) to use the brakes.

Low and Slow

Low and slow is a rewarding and enjoyable kind of flying that many pilots manage to miss out on. My glider CFI explained a similar phenomenon, that gliders are enjoyable to fly because you’re actually flying them, all the time. Many student pilots drop out right after soloing because they soon transition from maneuvering the airplane to flying mostly straight and level.

Wiebe says that he has, “invested a lot of money in a better flying experience.” He’s onto something. Low and slow, observing the earth, being part of the atmosphere, with high sensory input—the Belite offers that kind of flying. And it does so in a way that pilots of “real” airplanes will have to reassess their preconceived views on ultralight handling.

For more information, call 316/253-6746 or visit www.beliteaircraft.com.

Are Belite plans available to buy?