In my role as a columnist for this magazine, I’ll now be writing “Maintenance Matters,” a new every-other-month feature designed to educate readers about the basics of, well, aircraft maintenance. I’ll include tips and recommend tools I’ve learned about over the last 40 years.

The author on the job, circa 1988.

My aviation maintenance education began in the U.S. Navy. After getting out I attended airframe and powerplant (A&P) school in May 1970 at the Northrop Institute of Technology (NIT) in Inglewood, California. We spent four hours each day in shop and four hours in class, got two weeks off at Christmas and two weeks off during the summer, and completed the training in 14 months.

The school required students to purchase texts such as Basic Science for Aerospace Vehicles, Maintenance and Repair of Aerospace Vehicles, and Powerplants for Aerospace Vehicles, which were written for NIT by James L. McKinley and Ralph D. Bent.

The NIT textbooks were the leading texts for A&P schools in that era. Today aviation companies such as Aviation Supplies and Academics (ASA), Jeppesen, and King Schools offer A&P course books, tests and DVDs. All are well done and can be helpful.

Lessons Learned from School

I spent the first month at NIT in basic shop where we built a specialized tool using nothing but files, a drill press, hacksaws and thread-cutting tools. Those basic hand-tool skills have stood me in good stead for decades. Aircraft owners and builders need basic hand-tool skills.

Basic hand-tool skills will stand you in good stead during maintenance tasks.

The second skill I learned that has always kept me out of trouble is to get instruction on tasks I haven’t done before, or to at least get someone to talk me through a new task. I also learned to go to the book, and by that I mean all of the manufacturer’s publications including the latest service information updates in the form of bulletins, letters and notices to augment what is in the basic manuals. For instance, the Lycoming overhaul manual for all direct-drive engines is 3⁄8 of an inch thick. A service table of limits and torque value recommendations book is also 3⁄8 of an inch thick. Lycoming service bulletins, service letters and service instructions fill 7¾ inches of bookshelf space.

After A&P school I moved to Seattle where I worked in the mockup shop at Boeing Aircraft for about six months, installed Fowler flaps systems on 400 series Cessna twins for Robertson Aircraft and helped out at the Aero Sport Flying club on Boeing Field. These jobs helped me develop my skills in sheet-metal fabrication, reading installation drawings, drilling out rivets, fitting and installing modification kits, and techniques for bucking rivets in restricted spaces. Nothing takes the place of hands-on practice to develop skills. More on this later.

Audrey Knight’s experience included being a mechanic’s helper on a B-25. Married to the author, she sometimes assists in the maintenance of their airplane.

Why We Need to Think About Maintenance

The amateur-built side of aviation is growing due to three factors. First, as shown in the December 2010 kit aircraft buyer’s guide in this magazine, which listed 320 designs, builders are free to pick from a wide variety of airplanes. If the goal is to build an inexpensive, low, slow, sightseeing airplane that sips auto gas, there are plenty to choose from. Or if you want to build a pressurized cross-country speedster, that is also on the menu. There are even kits for modern versions of historic airplanes such as the Mignet Flying Flea or the Fokker D-VII WW-I fighter.

The second reason, which goes hand in hand with the diversity of airplanes, is the freedom to install equipment such as an avionics suite that meets your needs at prices that are much more affordable than similar—and in some cases less capable—FAA-certified equipment.

Lastly, the regulations allow amateur-built airplane builders freedoms with respect to maintaining their airplanes. But with all of these freedoms come responsibilities.

Maintenance and Mods

Almost anyone can perform maintenance on an amateur-built airplane. But there are a couple of catches.

The defining document for Experimental/Amateur-Built aircraft is the operating specifications (ops specs), and most often it includes a sentence that reads something like this: “This aircraft may not be flown after incorporating a major change as defined by Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 21.93 unless the owner has notified the FAA and their response is received in writing.” What does that mean? Here’s the FAA’s definition. A “minor change” is one that has no appreciable effect on the weight, balance, structural strength, reliability, operational characteristics or other characteristics affecting the airworthiness of the product. All other changes are “major changes.”

Suppose a builder decides to install a new propeller—the vendor promises a vast improvement in performance. Yet there’s no data from either the propeller manufacturer or the FAA certifying that the builder’s prop/engine combination has passed reliability testing. Does installation of the prop constitute a major change? You bet.

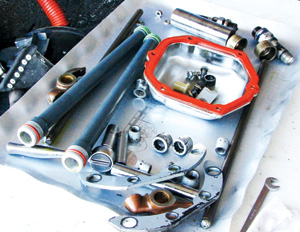

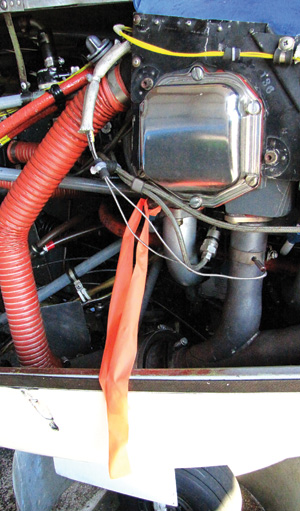

Placing a flag on the part you were working on will allow you to readily pick up where you left off when you return.

By contrast, all maintenance on certified aircraft with the exception of preventive maintenance tasks as defined in Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 43 Appendix A must be performed by an FAA-certified mechanic or be supervised by a certified mechanic. (An owner is permitted to do all of the maintenance if supervised.) The definition of supervised means the mechanic must be readily available, in person, for consultation and must ensure the work is done properly.

Is the owner of a certified airplane free to install a modification or upgrade? Not unless the modification or upgrade has been approved by the FAA. It can be approved by Supplemental Type Certificate (STC), or through a one-time approval process by an individual FAA maintenance inspector. The one-time process is called a field approval.

Kit aircraft builders don’t need these approvals—the responsibility for determining whether the product is suitable for installation rests with the owner.

Inspections

Experimental/Amateur-Built airplanes must be given a “condition inspection” every 12 months that follows the general checklist of items in CFR Part 43 Appendix D. Lo and behold, that’s the same checklist that the FAA provides for annual and 100-hour inspections on certified aircraft. The 100-hour inspections are identical in breadth and scope to annual inspections and are required on aircraft used for hire such as flight school or charter work. The 100-hour can be signed off by a certified mechanic; the annual must take place by the last day of the twelfth month after the last annual and must be signed off by an A&P mechanic who holds an FAA Inspection Authorization (IA).

Condition inspections must be signed off by an FAA-certified mechanic holding airframe and powerplant (A&P) certificates, or the owner if he holds a repairman certificate for his airplane. A repairman certificate for an amateur-built airplane applies only to the builder’s own airplane—he can’t use it to sign off a condition inspection on his neighbor’s airplane even if it’s exactly the same type.

Work Logs

Every kit aircraft builder must develop the practice of keeping a detailed work log. In order to issue a repairman’s certificate to the owner, the FAA requires that the owners prove they have done the majority (usually referred to as 51%) of the work on the airplane. The work log is the builder’s proof.

The work log will also help track maintenance, and reviewing the work log will reveal maintenance trends.

To ensure safety and airworthiness of an airplane, both the airframe and the engine must be maintained. Reviewing the work log will show if maintenance is balanced. If you’re not spending enough time noodling on the engine or lubing and maintaining airframe items, the log will point that out.

Inexpensive digital cameras and personal computers have made it easy to create and maintain a work log. Use Microsoft Word or a similar program to set up an aircraft maintenance log (file) and add documents identified by date and subject to create a log. Insert photos to illustrate hard-to-describe procedures. I keep a digital camera in my toolbox just for this purpose.

A well-kept log will help you grow as a mechanic and will provide guidance in formulating and maintaining a comprehensive and well-rounded maintenance schedule.

Developing a Maintenance Schedule

At the very least a maintenance schedule must include engine preventive maintenance tasks such as oil and oil filter changes at 50 operational hours or four-month intervals (whichever comes first), induction air filter cleaning or changes every 100 hours or annual unless operating in dusty conditions, carburetor or fuel-injection inlet screen inspection and cleaning every annual, magneto-to-engine timing checks and adjustments every annual, and spark plug inspection, cleaning and rotation every annual inspection. Of course, specific guidance from the engine manufacturer or airframe designer will supersede these general recommendations.

Airframe maintenance must include main fuel strainer screen inspection and cleaning every annual, lubrication of hinges, joints, linkages and wheel bearings every annual, inspection of brake pads, hoses and disks for condition and wear every annual, and a thorough visual inspection of the fuel system components such as selector valves and filler caps for operation.

This list is just a beginning. Download the inspection checklist in CFR Part 43 Appendix D from the Internet. Use it as a baseline to create your own airplane-specific maintenance inspection schedule. Builder’s forums are also an excellent place to ask for and get guidance on maintenance issues.

Manuals and CDs are helpful in the shop. This is one of the author’s favorites.

Supplemental Materials

When I bought a VW bug my uncle Bob handed me a copy of Henry Elferink’s VW Technical Manual. This book stressed the three keys for maintaining air-cooled engines: Set the correct valve lash; set the correct ignition timing; and set the correct idle mixture and idle speed. I’ve used these three rules to maintain aircraft engines up through Pratt & Whitney radial R1830-94 engines and believe they are the cornerstone of air-cooled engine maintenance.

All builders and owners who do their own maintenance need access to FAA Advisory Circular AC 43.13-1B and AC 43.13-2B. This AC is titled Aircraft Inspection, Repair, and Alterations: Acceptable Methods, Techniques and Practices. This is the bible for light airplane maintenance. This weighty circular can be accessed free of charge at the FAA’s web site.

I keep a paper copy, but there’s also a version on CD that everyone working on airplanes should own. John Schwaner of the Sacramento Sky Ranch is the author of the Sky Ranch Engineering Manual and the interactive CD titled Mechanic’s Toolbox and Engineering Manual Companion. If I could afford only one publication to guide me in aircraft maintenance, I’d buy a copy of Schwaner’s Mechanic’s Toolbox. This CD is chock-full of ready reference material. Need to find the right firewall sealer? No problem. Need to get a part number for an O-ring? No problem. Schwaner’s CD is invaluable, and at less than $40 it’s a steal.

Another handy toolbox-sized reference book is the Aviation Mechanic Handbook by Dale Crane for ASA.

Adventures in Mechanic-Land Continue

After working as a mechanic for Aero Dyne, a non-scheduled contract freight company that operated six DC-3s, for four years I went back to school to strengthen my understanding of electrical circuits and avionics.

During the summer break from school I was hired by an Alaskan freight hauler operating out of Soldotna, Alaska, to swing wrenches and hold down the right seat of the DC-3 for a flight or two whenever one of the real pilots fell ill. The company leased an Aero Dyne DC-3, a DC-6 and a Lockheed Electra to haul salmon from the western fishing grounds to processors in Anchorage.

After I finished school I toted my toolboxes from the shores of Lake Washington near Seattle, to Laredo on the Texas/Mexico border to work as the Director of Maintenance on a two-DC-3 freight operation. That job ended, but not before I bought a 1947 Piper PA-12, which I commenced to fly from Corpus Christi, Texas, to Alaska. All day VFR and all “I Follow Roads” (IFR). It took 50 flight hours.

I opened a small aircraft maintenance shop in Soldotna, Alaska, and soon found that I wasn’t much of a business man. In 1992 I called my brother, who flew up from Seattle and helped me drive back down to Washington state. My more recent professional history includes work as an editor for the Cessna Pilots Association magazine and for the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA).

Next time we’ll look at setting up a shop space where you can conduct your aircraft maintenance tasks.

If you have questions or want an explanation on a particular maintenance subject, email [email protected] and put Maintenance Matters in the subject line.