“Customers are always right except in matters of money.” Those stark-but-telling words were emblazoned on a sign in the break area of a fast-food chain where I worked for an all-too-long week in 1985. A seller’s terms and conditions—those not hidden in an employee break area—form a contract between a buyer and a seller. (Before you skip to another story in this issue, give these 1300 words their due. I’ll try not to make this read like terms and conditions.)

Terms and conditions are the house rules, in place to eliminate surprises and protect buyer and seller alike though, admittedly, the seller writes the rules. Commonly, terms and conditions define how payment is accepted (“personal checks delay shipping 10 to 14 days”), how discrepancies are resolved (“defective parts are repaired or replaced at seller’s discretion”) and when returns are authorized. When you do business with a seller, you agree to their terms and conditions whether you read them or not. I’ve seen terms and conditions for a key chain that are three times longer than this column. Others are short: “We’ll do what’s right.” I love that sentiment but it requires everyone to do what’s right. If that were always the case, a key chain wouldn’t need a 3600-word contract.

Pizza With Extra Sass

Within arm’s reach of my keyboard lies a $1-off pizza coupon. As a levelheaded consumer, I don’t need to read the fine print for the coupon to be clear: “One dollar off Brand-X pizza when I buy one Brand-X pizza. Good through 12/31/2022.” Simple. If I use it for a Brand-Z pizza, or use it on New Year’s Day 2023, an alert cashier will refuse it. If I ask for $2 off, the cashier will give me a puzzled look and take $1 off my pizza purchase. My only appropriate reaction is to acknowledge my error or unfounded request, not berate the cashier, demand he be fired, spit venom on anti-social media platforms and threaten a lawsuit. Speaking of that…

An attorney wrote on an aerobatic group that he was going to spread anti-AeroConversions flyers around the Sebring Sport Aviation Expo “…unless that ***hole in tech support is fired.” I had denied his return of an air filter after he claimed it made his modified certified aircraft quit on takeoff. He felt the denial was a corporate-culture money grab (it’s a $68.25 accessory) and I was endangering people’s lives. His demand for a refund ran smack (that’s not a legal term) into the term that there are no returns on used merchandise. He threatened a lawsuit and, oddly, threatened his life by stating he’d reinstall the air filter and attribute his all-but-certain death to the air filter. You’d think an attorney would have read the contract he agreed to—if not before the purchase then certainly sometime after. You’d think a pilot would know a PIC is responsible for the airworthiness of the airplane they command. Few, if any, kit-airplane companies sell parts for trial, especially with amateur labor the target consumer. (The only ordering policy in bold font on the Van’s Aircraft web store states, “Important: The buyer is responsible for determining the suitability and application of the product.”)

Two Guys Walk in With a Bar

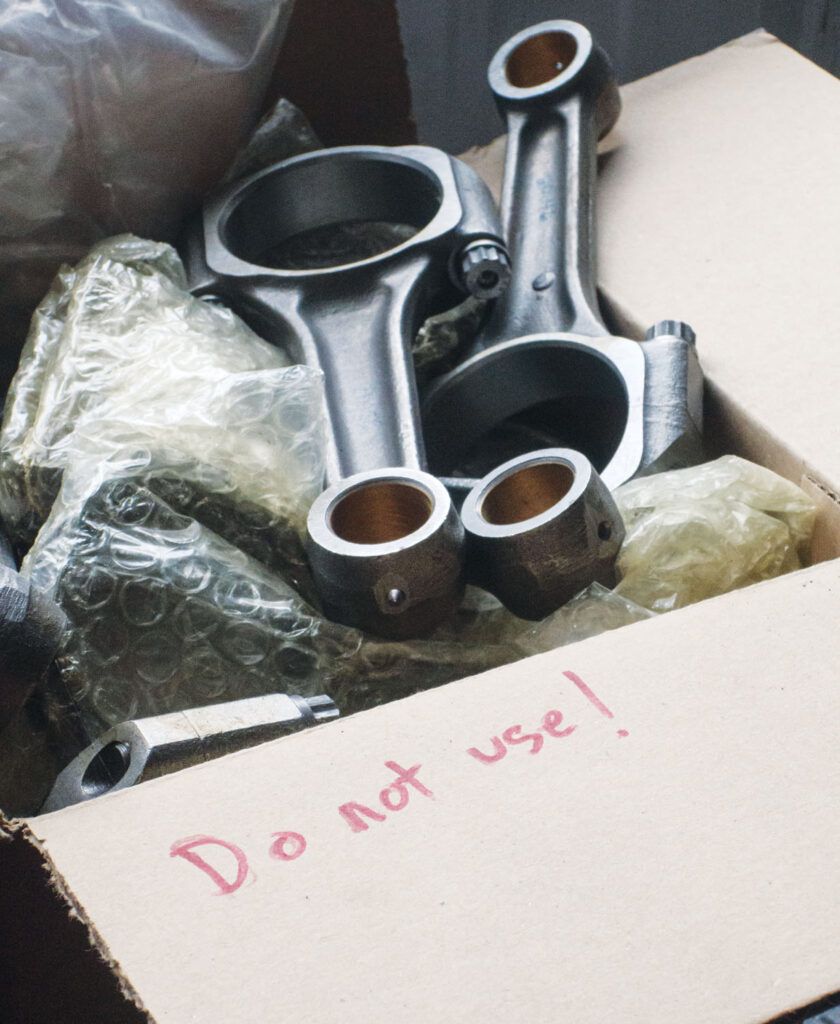

Two building buddies came to me with an elevator pushrod that didn’t match the plans. They wanted to exchange it for one that did. Their pushrod had a rough, un-powdercoated attach plate welded at an unusual angle. I had questions. The kind of questions you have when you find a peanut butter sandwich in your VCR or kerosene in your push mower. Their invoice history revealed the part was years old. They swore the part was as they received it and I assured them it wasn’t. Still, I did due diligence. Could a prototype/experimental part have escaped R&D and gone on the lam in their kit? No. The men weren’t happy the part wouldn’t be replaced. Later, one remembered they had modified the part. And right there a term (30 days to report missing or defective parts) was helpful because common sense failed when it should have prevailed. In this hobby, parts can take years or decades to be put in use. In that time they can be lost, modified, damaged, change hands and deteriorate.

A Woman Makes a Flap

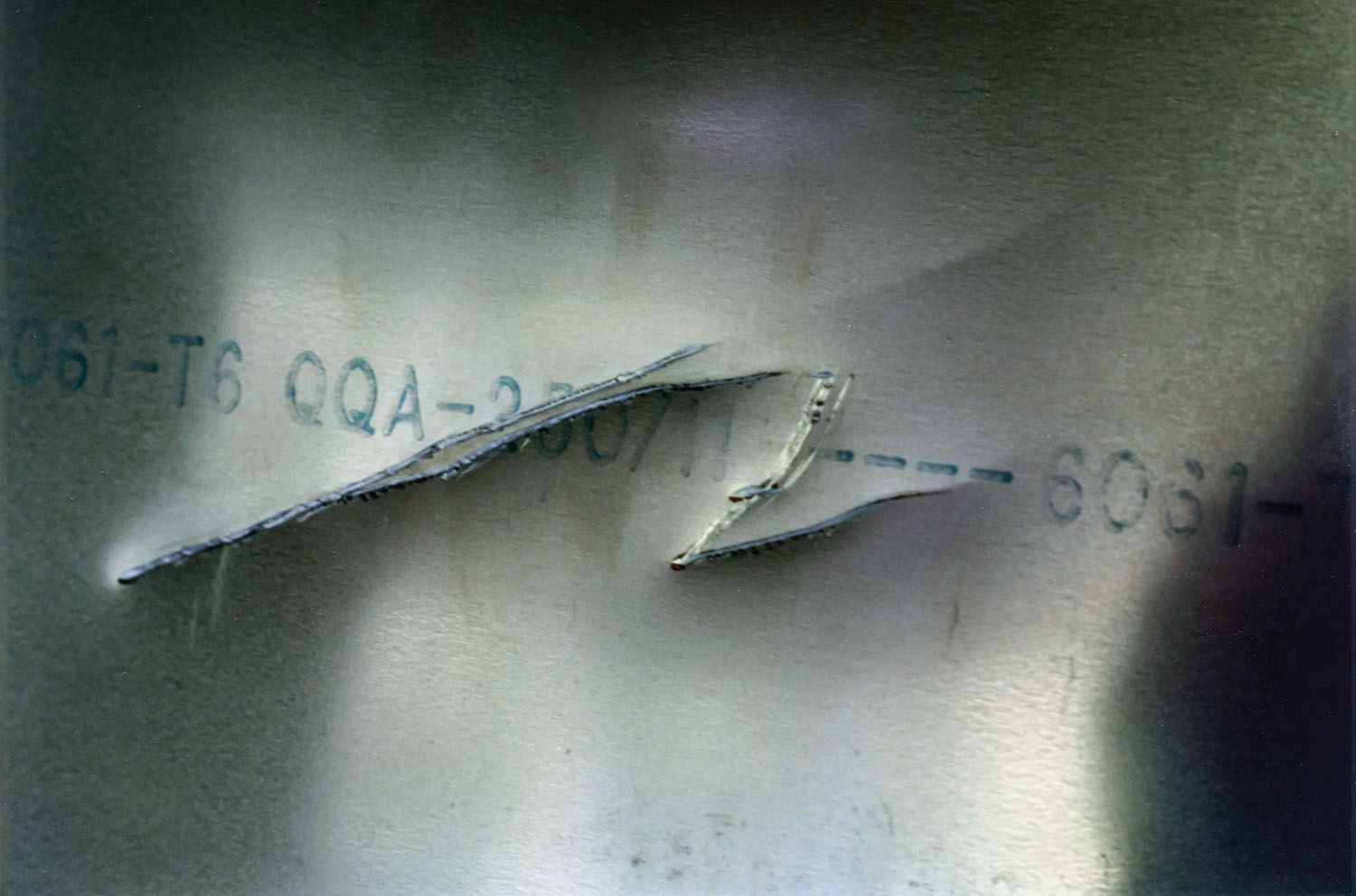

“I just pulled a flap skin off my shelf and it’s severely damaged. I can’t believe you’d ship something like this!” A few things to, ahem, unpack here. If the damage was obvious, why did she miss it when she unpacked the box and placed the part on her shelf? Was the package inspected on delivery? After a shipping department turns a package over to a shipping company, they lose control of it. In most cases, sellers require buyers to file a damage claim with the shipping company. But there is potential for damage that isn’t evident in the packaging, which is why a package’s contents should be examined immediately to make sure the contents are in good condition. A seller has an obligation to ship a serviceable part properly protected for transit. A reputable company will replace a poorly packaged part. The time frame for reporting damaged or missing parts is often defined in a company’s terms and conditions. Common sense suggests it’s a fairly short window of time.

Dear Dad, I’ve Joined a Band

On several occasions entire boxes of parts have been reported missing from an airframe kit. One of the most entertaining shortage claims I’ve had was resolved when the builder found his missing box propping up his son’s drum set. Had the customer performed the kit inventory and inspection within 30 days of receipt, as defined by the terms and conditions, he would have accounted for the box before it struck out for a future in rock and roll. That, in turn, would have narrowed his search pattern and saved days of earnest emails with me. Reporting missing parts months into a build is like claiming a scratch on your six-month- old car happened at the dealer.

It Needs To Be Said

Some terms and conditions define what you can’t do. For instance, you can’t copy and distribute plans or manufacture and sell airframe parts. That may seem obvious, but it happens. I recall a builder who began manufacturing and selling parts to “recoup his investment” in his kit. A kit aircraft designer has every right to protect their engineering and financial investment by protecting their proprietary information. Start selling Elvis mugs and see how long it takes the suits at Elvis Presley Enterprises to deliver a letter filled with words averaging four syllables or more demanding that you stop. Most encroachments are innocent and a builder only needs to be told to stop. Sometimes it’s intentional theft and legal action must be taken. Trust me when I tell you kit manufacturers are as eager to involve attorneys in a dispute as a builder is to be served papers.

Whether it’s a pizza or a powerplant, if you don’t familiarize yourself with the terms and conditions in advance of a purchase you’ll need to accept them if an issue arises. A reputable company with a solid track record will strive to do what’s right. That’s why they have a solid track record. That’s also why they define how they conduct business. There are no surprises that way. If you want a slow-paced hobby, watch the terms and conditions of upstart kit aircraft companies grow over time. Each new entry is the child of a troublesome transaction because “we will do what’s right” doesn’t work as well as everyone would like.

Kerry – don’t worry.

I think most PIC’s know that Mr “flyers around the Sebring Sport Aviation Expo “…unless that ***hole in tech support is fired” has an axe to grind and their opinion is suspect at best.

But I still want $2 off my pizza…… 😉

There’s also the situation where the buyer cannot know what is missing as I experienced with Vans. A part that was not inventoried because it was built into the quick build fuse only became apparent later

The suggestion from vans that “ you must have mislaid it” didn’t help

Hi Ian,

Hopefully that situation worked itself out in your favor, in time, as it should have. I think all kit companies can fall victim to individuals in individual departments not having all of the information they need at times. Whoever told you that may not have known that part was built into a quick build airframe rather than delivered as a separate part. I’ve seen it happen at Sonex, where internal miscommunication or an errant packing list can result in a “missing” part. We always do our best to correct the issue and the paperwork so it doesn’t happen again.