The author’s Texas Sport (Legend) Cub. A combination of Poly-Fiber fabric and Air-Tech paint and primer produced a great looking fabric job. Note: Do not assume mixing products from different manufacturers will produce good results. Do your research first. (Photo: Marc Cook)

Even though aluminum is by far the most popular material used as the skin of an airplane, there has been a resurgence in the popularity of fabric covering that parallels the growing interest in Cub-like kit airplanes. The experimental builder will find a number of fabric covering systems to choose from, but most of them use very similar procedures. The two biggest departures from standard practice come from Stewart Systems and Oratex, but even they incorporate many of the same basic practices as the more traditional systems. For those who are doing historically accurate restorations or recreations, systems using Grade A cotton or linen may be required, but we will not deal with those here because they are not popular with experimental builders.

When considering best practices, the system manufacturer’s installation instructions should be your primary source of information. Applying things learned from previous experience with a different system may get you into trouble, if you ignore the unique requirements of the system you are currently using. You simply can’t know what best practices are if you don’t read the instructions.

Preparation

Good preparation of the surface to which the fabric will be attached serves as the basis of any good fabric job, regardless of the system used. Good preparation means that all dirt, grease, and any other deleterious material must be removed. Even brand-new tubing will need to be cleaned and roughed up slightly to encourage good adhesion of the primer coat. After that, the tubes or wood structure must be coated with something that is compatible with the fabric system being used. This is typically an epoxy primer of some sort. If tubes are going to be exposed to view after covering, now is the time to apply a compatible color coat over the primer. In all cases the tubes or wood being covered need to be protected from rust or rot. They then must also be coated with a product that is compatible with the adhesives in the covering system. Consult the manufacturer’s literature for specific recommendations.

Anti-chafe tape gets applied to sharp corners and small protrusions such as rivet or screw heads before any fabric gets installed.

If you are recovering a previously covered structure, be sure to remove 100% of all the old fabric and adhesive. MEK solvent usually does a good job of removing fabric and glue, but if there is a lot of flaking paint or rust present, proper cleanup may require extensive sanding or media blasting. Old paint does not need to be removed if it is in good condition, but all fabric and rust must be removed and bare metal primed before proceeding with a covering job.

If you have any dents in leading edge surfaces or other areas that you do not want to see when the plane is covered, now is the time to take care of them. Use an aviation-type filler as per the fabric system’s recommendations for this (usually an epoxy filler). Do not use automotive Bondo.

The last preparation step is the application of anti-chafe tape. This goes at sharp corners and over screw or rivet heads or other small projections. There is no set rule for the use of anti-chafe tape, but it is important to protect the fabric from anything that could cut it or easily wear through. Never use masking tape, duct tape, or aluminum tape as a replacement for anti-chafe tape.

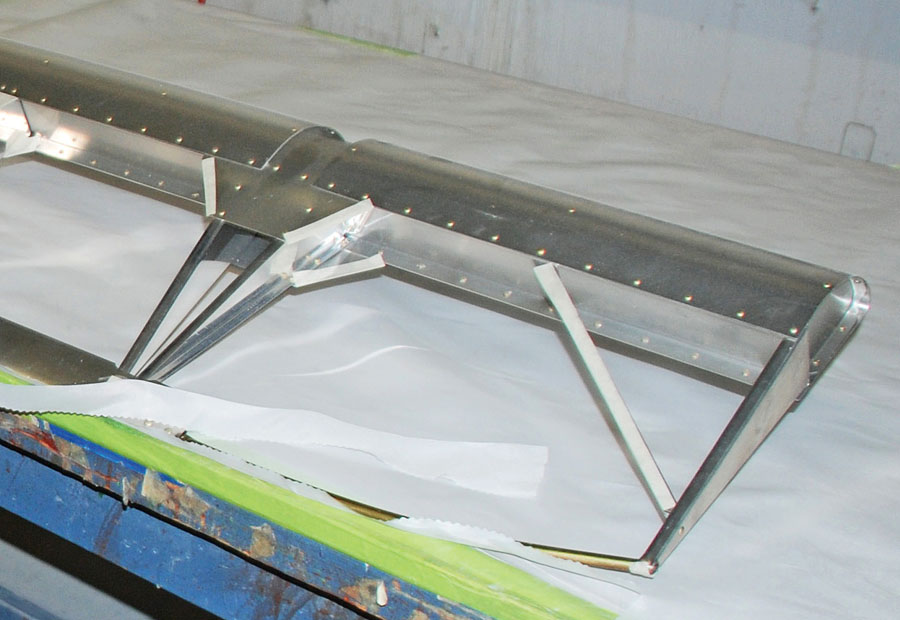

Here is a complete, covered wing. The round spots are reinforcing rings for future inspection holes. These are made by covering plastic rings with fabric in strategic locations.

Select a System

If we eliminate nitrate and butyrate dope-based systems as an option, something I would strongly recommend unless there is a very good reason not to, we have these options: Air-Tech, Poly-Fiber, and Superflite as the solvent-based systems, the water-based Stewart system, and Oratex, which is a unique system that we will address later. The main difference between these systems is that the Stewart system uses water-based adhesives and paints that are more environmentally friendly and less toxic. I don’t know that any of these systems can claim to represent best practices over the others. They are all good products that can achieve good results if used properly.

They all use the same basic polyester fabric, but with subtle differences in the case of Superflite. The Stewart system uses Superflite fabric and tapes. Air-Tech and Poly-Fiber use fabrics and tapes that appear to be identical, but the Air-Tech fabric has a Ceconite stamp on it, and the Poly-Fiber fabric says Poly-Fiber on it. The medium and lightweight Superflite fabrics are slightly lighter than those by Poly-Fiber or Air-Tech.

A household iron works well to shrink fabric. Just be sure to check the temperature of the iron in several spots on the heat plate, especially when working at 350 F. Aircraft Spruce sells these irons for as little as $35.

The important consideration when it comes to fabrics is the weight to be used. Poly-Fiber and Air-Tech have three weights available. The heavy fabric weighs 3.5 ounces per square yard. It is best suited for aerobatic planes and others that have high wing loadings or will be subject to rough use. The more popular medium fabric weighs 3.16 ounces per square yard. This is the weight of fabric that most builders will use. Superflite has a lighter medium-weight fabric that comes in at 2.7 ounces per square yard. This will make a difference of something less than two pounds on a typical Cub-sized plane. There is also a very light fabric that weighs 1.87 ounces per square yard (1.80 for Superflite) that is only suitable for planes with a wing loading of less than 9 pounds per square foot, which would typically be ultralights or Light Sport airplanes.

On large areas, a Crain Model 920 S carpet seaming iron did a better job of holding a consistent temperature over the entire heat surface.

If we are going to talk about selecting a system, we can hardly ignore Oratex. This unique system, first made popular in Europe, has made its presence felt in the U.S., too. The Oratex system comes with the color and UV protection impregnated into the fabric, so that painting is unnecessary. It uses glue that is activated by heat and pressure to bond the fabric together and to the aircraft structure. There is a lightweight version, called Oratex 600, that is equivalent to the lightweight Superflite and Poly-Fiber products and is limited to Light Sport planes (gross weight no more than 1320 pounds). The standard-weight Oratex 6000 is rated for planes up to 13,228 pounds. Its strength exceeds the strength of the heavyweight Poly-Fiber or Superflite, so it could easily be used on aerobatic airplanes.

Oratex 600 weighs about 3 ounces per yard, and the 6000 system comes in at about 4.5 ounces per yard. Although these weights are heavier than the equivalent strength Poly-Fiber or Superflite products, it is important to remember that Oratex includes integral color, so the weight of primer and paint needed with the other products is, in effect, included. In fact, the weight savings that comes from using Oratex to cover a typical Super Cub airplane is about 30 pounds.

The downside to Oratex appears to be price, but if the required paint for the other systems is included, the extra cost quickly disappears, as does a great deal of labor, and the labor factor is big. Over half the time to cover an airplane is needed to prime, sand, and paint the fabric after it has been installed. Oratex eliminates all of that. The real downside is that Oratex cannot achieve the same level of overall appearance without it being painted, too. This is not to say that an Oratex-covered plane is unattractive, but it is arguably less attractive than the results that are possible with, say, Poly-Fiber and a high-gloss urethane paint. The final argument against Oratex is that it has only been around for about 10 years, so its track record, while good, is limited.

In short, if you are very focused on saving weight and/or wish to avoid the considerable hassle of priming and painting fabric, Oratex is worth a hard look. If, on the other hand, you are trying to build a grand champion show plane, it is really not going to give you the look you need to dazzle the judges. As for what is the best covering product, that will depend on what you wish to achieve. They are all good products that can provide you with many years of good service if properly installed.

The Fabric Covering Process

As is always the case, if anything here is contrary to the recommendations of the manufacturer of the system you choose, then you should follow their instructions and ignore what is here. That said, there are many workmanship points that are common among all of the various systems. When attaching fabric to fabric, or fabric to structure, the best practice is to have a continuous bond that is at least one inch wide. On the leading edge of the wings, that should be increased to two inches. These bonds then get covered with two-inch-wide tape with pinked edges, except at the leading edge of the wings where four-inch tape is used.

Ed Zaleski (left) watches Dave Prizio stitch the fabric on the horizontal stabilizer. Special rib stitching needles, available from fabric suppliers, work best, as does the flat (as opposed to round) rib stitching cord.

Protrusions need to get extra reinforcing around them, as do any hard edges, such as the stringers that form the shape of a Cub fuselage. Rib stitching or other forms of fabric-to-wing attachment also get taped. As a general rule, any place where a structural element makes contact with the fabric covering, the builder should reinforce the fabric with two-inch tape or a patch cut to fit an irregular shape if such is the case.

Reinforcing rings around possible openings should get covered with a patch of extra fabric. These are most commonly seen in wings where inspection holes will be required, but such openings could also be present in the fuselage covering. Grommets for drain holes are treated in a similar manner and should be provided anywhere that may trap moisture inside wings or control surfaces.

Once the fabric is glued in place, it is time to tighten it with heat. With Ceconite and other polyester products, this is done in three steps at increasing temperatures—250, 300, and 350 F. This can be done with a common household iron, but a small hobby iron can be very handy for certain operations in tight places. Usually the cheapest, simplest irons work best. I have also had good luck with a carpet seaming iron. The key is to get an iron that has a fairly consistent temperature across its plate and to check it regularly with an accurate thermometer. I prefer a non-contact infrared thermometer for this. Another really important thing to remember is that polyester fabrics melt at 425 F, so a too-hot iron can ruin your work in a second.

The fabric around protrusions such as this step on the gear leg should get extra reinforcing. There is no fixed standard for the size or location of these reinforcing patches. It is probably best to be generous with these.

During the initial covering process, it is important to not try to tighten the fabric as you are attaching it. The heat-shrinking process will take up a lot of slack in the fabric. If all of that slack has already been taken away, the fabric could end up being too tight and possibly even bending the structure to which it is attached. This brings up a good point, that frail members will need extra reinforcing if fabric is to be attached to them. Otherwise they may bend badly out of shape during the tightening process.

The fabric on wings and control surfaces will need to be stitched (or clipped or riveted) to the structure. Before stitching, reinforcing tape is attached to the fabric along the lines of the structure where stitching will be required. Holes are then punched in the fabric, top and bottom, where the stitching will go. Rib stitching spacing will vary depending on the speed of the airplane and whether or not the stitching will be in the slipstream of the propeller. The basic guidelines are in AC 43.13-1B. For planes that have a VNE of less than 170 mph, rib stitching in the prop wash area should not exceed 2 inches on center and in other areas 3 inches on center. In all cases compare the kit manufacturer’s recommendations and the fabric system guidelines to confirm this spacing. Once stitching is complete, cover all of those areas with two-inch pinked tape.

A last step to the fabric covering process is to go over every joint and taped seam to be sure everything lies flat and has no raveled edges. It is just like preparing to paint anything else. If the underlying work is rough, the final product will look rough, too. This is your last chance to get it right before paint.

Note that while heat guns are strongly discouraged by the manufacturers of polyester covering systems, Oratex actually recommends using a calibrated heat gun. To be sure, this is not the $10 heat gun you can get at Harbor Freight, so expect to spend some money on a good heat gun if you go with Oratex. Its higher melting point of 485 F makes it more forgiving of less accurate temperature control and poor technique.

Fabric is applied to the bottom of the wing first and then the top with a minimum two-inch lap at the leading edge. The sequence is more of a convention than a necessity, but the lap is important. A four-inch tape with pinked edges is applied over the lapped fabric on the leading edge of each wing to give it extra protection. This tape should be applied after (and over) the tapes covering the rib stitching.

Priming and Painting

All fabric, except Oratex, needs to be primed to protect the fabric from ultraviolet light. But before we apply primer, you will need to apply two coats of what Poly-Fiber calls Poly-Brush, which is the same chemical mixture you used to attach the tapes and reinforcing patches to the main body of the fabric. Other manufacturers will have their own similar products.

With the fabric now fully sealed with a consistent surface, it is time to apply the primer.

After the fabric has been sealed it is time to apply the primer. The Air-Tech primer has the advantage of being almost white in color, so a separate white coat under the yellow finish coat was not necessary. Note the personal protection being used by the painter.

Each system will have its own priming requirements, but this important step should not be skipped or shortchanged. The sun is the enemy of fabric covering, so UV protection is vital. Primer should be sanded between each coat, but be sure not to sand over rib stitches or rivet heads. It is very easy to cut through the primer and fabric with overly aggressive sanding. Sanding with 320 or 400 grit seems to work well, with wet sanding generally giving better results.

After the first coat of primer, you will have an opportunity to do some minor repair work such as flattening curled edges of tapes or filling pinholes. Follow the recommendations of your system maker for this. Apply more coats of primer after you have made these minor repairs. Apply primer in a pattern that is perpendicular (cross coat) to the first to ensure good coverage. If you can see a 60-watt light bulb through the primer coat anywhere, you need to apply more primer. Once you have achieved that level of coverage, it is time to stop applying primer. More primer does not make it better. It just makes the plane heavier. Making the edges of the tapes disappear with layer after layer of primer is not a best practice. Poly-Fiber recommends against sanding the third coat.

Selecting the finish paint is your next task. Use a paint that is specifically designed to go on fabric covering. Automotive paints do not have the flexing agents necessary to stand up to the kind of use an airplane will get. Be sure to use a paint that will work well on fabric and metal or fiberglass. Don’t forget that even though most of the plane is covered with fabric, the engine cowl, boot cowl, gear legs, and struts are metal or fiberglass.

A careful cleaning with an approved paint prep and a pass with a tack cloth should precede the painting process. And don’t forget personal protection. Some paints, especially urethanes, are very toxic. A bunny suit and a fresh air respirator may be required. Read the manufacturer’s literature and MSDS to determine what personal protection you will need.

Fabric covering may look intimidating to the first-time builder, but it can be fun and is not especially difficult if you take a little time to practice first and carefully read the system manufacturer’s literature. Remember, best practices begin with a review of the manufacturer’s directions.

References

No matter which system you choose, I recommend reading Poly-Fiber’s How to Cover an Aircraft Using the Poly-Fiber System. Of course, where their recommendations differ from the ones provided by your selected system manufacturer, you should always go with those specifically made for your system. Poly-Fiber also has a video that is very helpful when it comes to mastering rib stitching. AC 43.13-1B is another good source of general information on fabric covering. See chapter two in that book, something that should be in every airplane builder’s library.