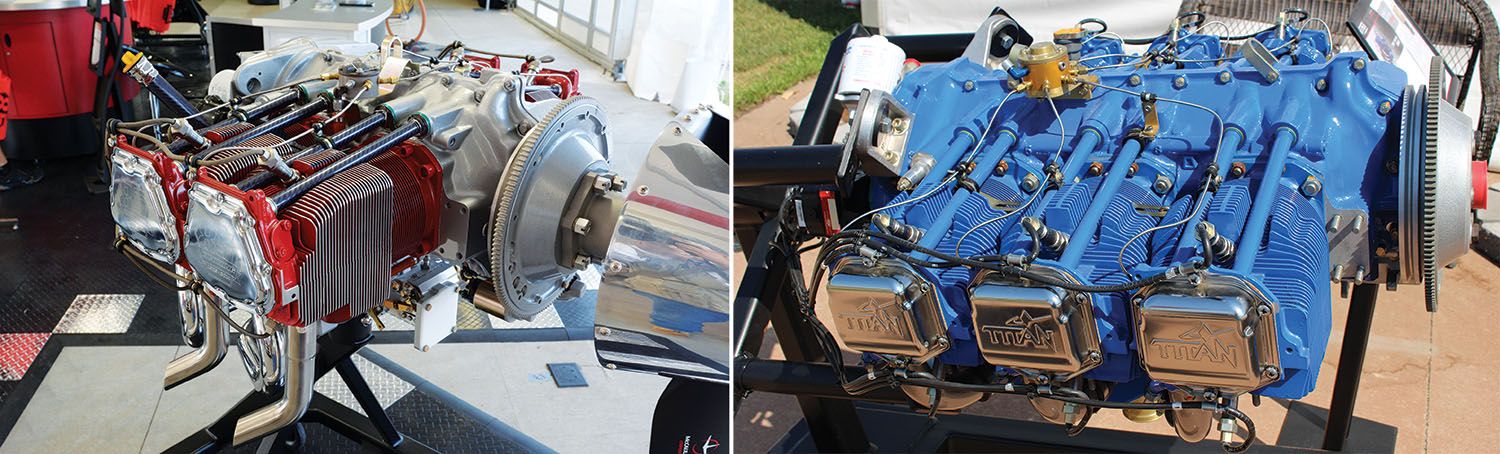

The future is going to look a lot like the present when it comes to Experimental aircraft engines. Sorry to be so mundane about it, but to be perfectly blunt 10 years down life’s Victor airway, engines familiar today will still be the main players, probably with fewer models sold in greater numbers. Almost certainly the four- and six-cylinder Lycoming architecture will increase its dominance of the mainstream Experimental/Amateur-Built category, with big-bore Continentals playing their part in the high-power niche, augmented perhaps—and we’ll inch out on a limb here—by a greater number of Chevy V-8 auto conversions.

Unless the sun starts rising in the west, Rotax should continue as the major motivator in the lighter plane market, followed by three- and four-cylinder water-cooled auto conversions moving VW derivatives even more to the economy market. Rotax could be a real change agent if they elect to move up into the 200-hp range, but we’ll also bet airframes will get slipperier, thus supporting good performance with Rotax’s current combination of lighter weight and around one and a quarter hundred horsepower. Again, that leaves the LyContinental Rex relatively unassailed in the big-bore amateur ranks.

Why so much status quo as the rest of the world races through technological change? In a word, cost. The general aviation market, much less our tiny sport aviation niche, is far too small to justify new development in the face of daunting regulatory and market hurdles. Today the world market for brand-new piston aero engines is less than a rounding error by industrial standards and the trend is downward. Ever since the great recession, sales of new piston-engine GA aircraft have struggled to reach 1000 airframes a year. The celebrated RV line has taken 48 years to see 11,000 aircraft (all single engine) produced. Call it maybe 300 new RVs a year these days. Our leather helmets are off to VanGrunsven, of course, but compared to the only real source of new piston engines—the automotive market—the aviation piston market essentially doesn’t exist. Ford sells an F-Series truck every minute of every day. The total U.S. light vehicle market wanders between 15 and 20 million units a year—nearly all with a piston engine—and around the world well over 60 million vehicles are built annually (114 vehicles per minute). Heck, the National Marine Manufacturer’s Association reports U.S. power boat sales were approximately 280,000 hulls in 2019, the majority no doubt being single-engine vessels. A final insult: Ferrari equals Van’s lifetime production every 16 months.

Instead, the aviation piston engine market is a rebuilding market. About 12,000 Lycs and Continentals get rebuilt in the U.S. per year, or so we’ve been told. Add up rebuilds, spit in the new engines, and the economies of scale can’t be found with an electron microscope. Scale counts as the price of each engine must be amortized over the production run. We’ve heard Detroit insiders speculate—no one can do the math—that an all-new auto engine costs $1 billion to bring to market. Especially when confronting the consequential headwinds posed by the cost of federal certification and, greatest of all, your and my obstinacy to pay, oh, $250,000 for an all-new, fuel-efficient, reliable piston engine in the 300-hp range, you can see that even a lean little company has trouble finding the cash to bring a game-changing, modern engine to market. For sure Engineered Power Solutions (Graflight V-8) and RED (AO-3 V-12) are trying, but it’s going to take Defense Department purchasing (big drones) to get those engines anywhere near the sport market. If only they could make it…

Déjà Vu

In fact, we’ve been through all this before. In the 1980s Continental developed the much improved and very capable Voyager liquid-cooled derivatives of their existing gasoline engines. The Rutans even proved the concept by flying one around the world un-refueled. “Too expensive,” said the market and that was the end of that.

Part of the cost issue is any 21st century piston engine must be Jet A-fueled. It is the only fuel available worldwide, not to mention its superior energy density and lower cost, so there’s nothing to dislike there. But such diesel engines are inherently premium designs. The high cylinder pressures require beefy construction throughout, plus the precision fuel systems are expensive and turbocharging is all but a requirement. Liquid cooling is probably a given, thus realizing the full benefit of such wonderful new engines ultimately requires new airframes that fully integrate the cooling systems. If general aviation had maintained both air- and liquid-cooled engines the last half century, we might not be facing such a huge step integrating modern engines today, but we are.

Certainly the current air-cooled fare is well entrenched. Granddad and dad flew one, so it’s good enough for me, a hugely powerful emotional undercurrent. Plus the rebuild industry is married to these engines, and why not? They’ve been around for 75 years, the parts are out there, and these uncomplicated engines lend themselves to simple rebuilding techniques. Until some huge market disruption—likely regulatory—comes along, the proven, developed LyCosaur is here to stay. And when they’re finally forced into retirement, we’ll miss ’em.

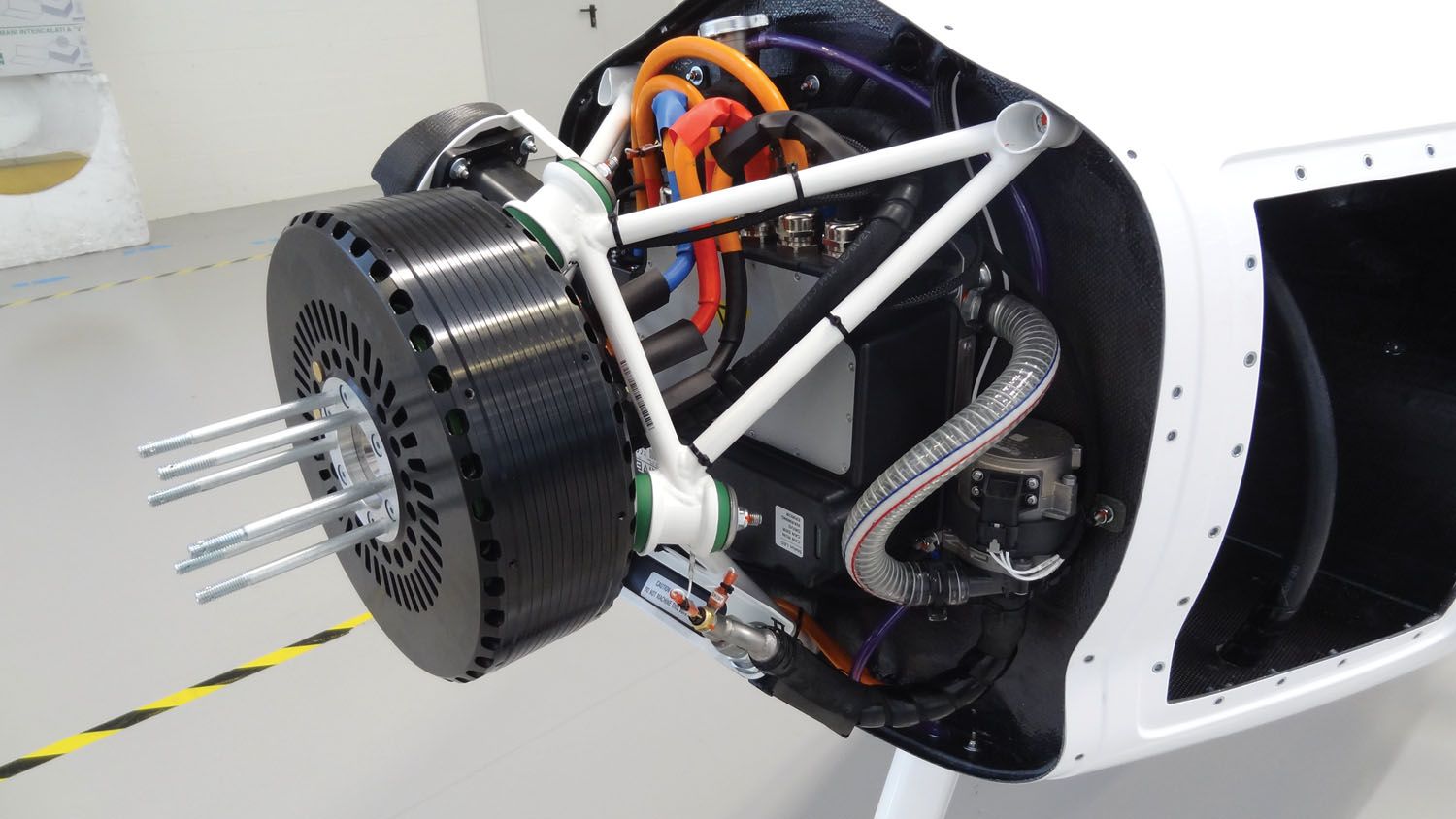

Ah, but electrics. Not a bad bet as there already is a tremendous effort to electrify commercial aviation, but even if this is where the investment money is, and even if some major industrialized countries have already outlawed the sale of internal combustion engines in the 2025 to 2035 time frame, the unknowns in battery development make this compelling but still emerging option too murky to forecast other than pioneering builders can already assemble limited-utility E-planes. What can be said is should battery-electric propulsion remain perpetually five years out, it is yet another threat to the development of new, more efficient piston engines. Why spend $100 million developing the world’s best Jet-A engine if it’s only going to end up in the bottom of a parrot cage thanks to some iPhone batteries and a permanent magnet motor? If a better battery, then that’s it for petrol engines.

Fuel cells? A wonderful solution, but even more speculative than battery-electrics at this point.

Back To Reality

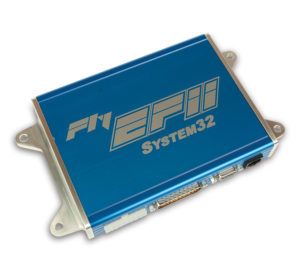

What is changing are the supporting systems around the current engines. So far the biggest success has been electronic ignition. In the E/A-B world some form of electronic ignition with variable timing is certainly mainstream in today’s completions; a decade from now they should have all but taken over save for the certified (read “antique”) market.

Next up is electronic fuel injection, meaning electronic engine management. Good systems are already available and gaining market share by the day. After decades of driving EFI cars people understand EFI’s advantages and are ready for the fuel savings. Yes, once the early adopters are on board, we might still see some “mass” market resistance and resulting hardware changes as single-point failure fuel systems are inherently less tolerant of sloppy installation than dual ignitions, but clearly EFI is the future.

With electronic engine management must also come a no-excuses robustness in electrical systems. Electrically powered, electronically controlled fuel and ignition systems are wholly dependent on the free flow of electrons, so only the best in electrical system design and execution will do. This seems an open area in engine accessories for the entrepreneur to address with kit-like dual alternator, harness and battery offerings.

As for the core engines, expect to see the growing marginalization of anything not a four-cylinder Lycoming. Otherwise fine engines such as Continental’s IO-360 six-cylinder have already bowed to the lower initial cost, lower rebuild cost and reduced weight of the stone-simple Lycoming. Even the Continental factory builds their own version of the Lyc, which is like Ford cloning Chevy engines, and this trend will continue until builders diversify from the RV family. Not likely.

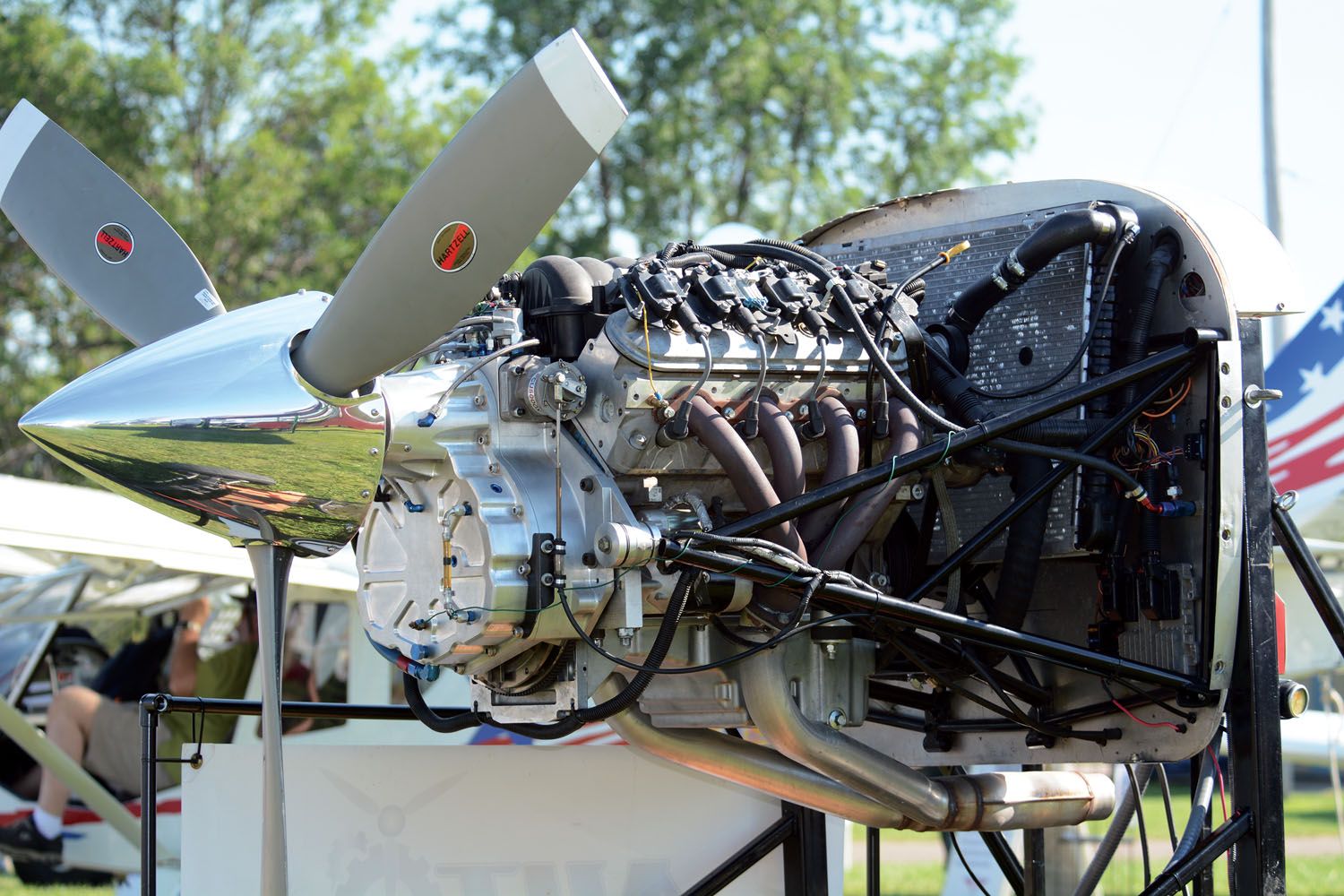

Of course, there are always niche markets within niche markets, and some of these might blossom. The late-model Chevy V-8 has proven itself durable, powerful and financially viable for aviation duty, and it could yet have its moment in the high-power market for those wanting to explore liquid cooling and narrow cowlings. Small, modern auto engines are also good aviation candidates in the lesser-power ranks. In fact, as auto engines have essentially reached perfection for cars, perhaps a greater number could be used in light-duty aircraft. But that’s a very complex subject for another day.

Finally, however improbable, what if small plane propulsion is taken over by someone outside the U.S.? China is the only viable entity, and a host of thunderclouds stand between red, white and blue Lycomings and a $19,000 crate from overseas. Still, American V-8 hot rodders went to Chinese rods and cranks 25 years ago; Continental is already Chinese owned and building Lycoming clones. Again, our market is too small to matter, but if the Chinese get serious about engines for their domestic needs, it wouldn’t be anything to ship engines here.

Photos: Tom Wilson.

Why no mention of DeltaHawk? Toss them a bone, do an update story, let builders

know what’s happening and what’s possible with a new Jet-A engine. I have been in the marine

engine business for 42 years and I think their engine has outstanding merit for not only aviation but

marine, standby power, farm & construction applications, The more applications the economies of scale

come into play and I’m sure the 4 cylinder concept that exists right now can grow into 2 cylinder, 6 cylinder

& 8 cylinder projects in short order. This will further reduce the cost to where replacing an old avgas

engines with a new Jet-A package will be financially attractive compared to a rebuild or a new avgas drop in.

What about Jabiru? Simple no-gearbox design with the smoothness of a 6 cylinder engine. Sales numbers of this Australian certified engine would be interesting.

Look at Turbotech! Turbine engine of 136hp for light aircraft. 5GPH in cruise. 3000h TBO.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OfdNoc_6vN8&t=35s

Flight tests expected this year.

Orders opening from Q4 2021.

Take a look at http://WWW.CORSAIRV8.COM

They have a V8 conversion flying in a Cessna with redundant EFI system and interactive engine gauge digital display. A lot of modern features and engine is flex fuel rated.