With today’s trend toward engine diagnosis via visual inspection of the interior of cylinders, more and more Experimental aviators are turning to the borescope market. We recently had an issue with one of our family airplanes that illustrated the point. My wife reported a rough-running engine and low EGT and CHT on cylinder number one as she returned from the local practice area to our airpark home. She reported it was the same on either or both mags—ruling out a simple fouled plug or broken ignition wire. Seeing as this is a high-time engine, I had all sorts of thoughts about broken or stuck valves and the time for overhaul. She had no trouble getting back on the ground, and another mag check on the taxi in confirmed that the problem was still there—cylinder number one was not firing on either plug.

Modern engine diagnosis is made easier with a quality borescope. Cylinder problems are easily diagnosed when you can simply look inside and see the valves, piston, and cylinder walls.

We pulled out the ATS Voyager Borescope that we had been testing, removed the top cowling, and the top plug from the recalcitrant cylinder. A hush fell over the hangar as I snaked the camera into the hole, and everyone looked at the screen, expecting to see broken, expensive parts. But such was not the case— on first glance everything looked fine. On a closer inspection, we could see that the fine-wire plug on the bottom was bridged —it looked like lead fouling. We then looked at the top plug that had been removed—and it too had a little blob of light colored material bridging the gap. Two fouled plugs in one cylinder—a rare coincidence, but not impossible.

The moral of the story? What might once have been cause for early removal of a suspect cylinder proved instead a simple diagnosis with the use of a borescope. At least we could relax the hands on our wallets much more quickly than if we hadn’t had a way to take a quick look.

The tools you use to do internal visual inspection have advanced rapidly in recent years. One of our neighbors has the Continental-recommended mechanical borescope that can be used to take a peek, but requires great skill at manipulation, lighting, and memory. There is no way to save a picture, or to even see it without peering in the eyepiece. Many of us own inexpensive borescopes from Harbor Freight or the local big-box stores that do provide a camera view—but they have heads that just barely fit through a spark plug hole and require mirrors affixed to the end to look around at all. Resolution on these units is not particularly good, but they are very useful for inspecting inside closed airframe structures for wasp nests, mouse droppings, or lost tools during final assembly.

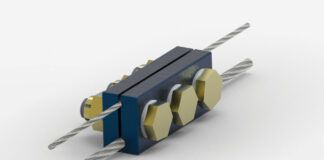

The Voyager comes with the articulating camera, a hand controller, and the viewing/control box for $1,299.95.

The ATS Voyager solves these problems—it has a very small camera head that can be articulated side-to-side via a knob on the hand controller. The operator can thus insert it into the cylinder (or other confined space) and manipulate it so that mirrors are not required. Using an optional case and harness, the screen and control portion of the system can be worn on the user’s chest so that the screen is visible, the hand controller with the knob to articulate the head can be held in one hand, and the scope itself manipulated with the other hand. Anyone who has used a scope of any kind has found that figuring out up/down, left/right from the image can be tricky—but with time, you get to where you want to be.

The image quality of the Voyager is excellent, with good focus up close and good color rendition. The lighting brightness can be adjusted from the controller to further allow good imaging. The LEDs surrounding the camera provide realistic color. The control head has a slot for an SD memory card, and the operator can save either single images or video. This is a huge advantage when documenting problems or if you want to share the imagery with an expert—or a group of experts on the Internet.

The Voyager viewing/control module allows you to capture images on an SD card for later viewing or sharing with experts who can aid diagnosis.

The quality of the Voyager is outstanding—just what you would expect with a high-end unit at this price. It comes with a rugged case and accessories. We found it awkward to use the control head/screen without the optional chest-mount case. Although it is certainly workable, you have to find a place to set it where it is visible while you manipulate the probe and the probe control head.

ATS also sells the Inspector scope for $500 less than the Voyager—the main difference being that the Inspector does not have the articulating head of the Voyager. We tested both and found that video and picture quality were identical—the only difference being that you had to use mirrors to look sideways with the Inspector. Having used mirrors before, we found the swiveling head to be superior, but the individual user will have to decide if the extra cost is worth the convenience. If you use the borescope every day, it might well be. For occasional use, you can get into a high-quality imaging system for a lot less money going with the Inspector.

For builders, mechanics, and pilots who maintain several aircraft, a quality borescope can be a very efficient way of evaluating sometimes frustrating engine or airframe problems. We have had times where the cost of a good scope saved hundreds of dollars in parts and many hours of disassembly to prove that the problem lay elsewhere. Inexpensive scopes will sometimes do the trick just fine, but for someone who values quality and well-designed tools, the Voyager is worth a good look.

For more information, visit Aircraft Tool Supply Company at www.aircraft-tool.com.

To submit a press release on a homebuilt-related product, e-mail a detailed description and high-resolution photograph to [email protected].