It’s true. Pitot and static systems rarely receive front-page billing in our hobby, but this area is of critical importance in any airplane large or small, and shouldn’t be overlooked.

The FAA describes pitot pressure as ram-air pressure picked up by a small, open-ended tube about a quarter-inch in diameter that sticks directly into the airstream, which produces a pressure proportional to the speed of the air movement. Static pressure is the pressure of still air used to measure the altitude and as a reference for airspeed measurement. This comes from Advisory Circular 43.13. Welcome back to Pilot 101.

So, yes, you probably already know all that, but consider that errors in the pitot-static system can lead you astray, especially if you’re IFR rated, equipped and inclined. But even for a VFR pilot, mistakes in the installation of a pitot-static system can lead to you chasing performance anomalies that aren’t there, or to attempting to fly faster or slower than advisable on approach and landing. Whether you are a builder, buyer or pilot, the pitot-static system should not be taken for granted. Accidents and incidents can be caused not only by blocked systems, but by poor installation, leaks, ice and other errors in either pitot or static sides of the system. Until you know your airplane intimately, you’re at the mercy of accurate airspeed readings, and they only come from good pitot-static practice.

Smarter Than the Rest

Its tempting as a builder to try and make yours better, and indeed many individuals have come up with creative ways to improve their aircraft over the stock, as-designed plane. However, when it comes to pitot-static (and fuel) systems, builders should resist the urge to experiment. As an example, there are 6500 RVs flying, and the majority of them use a simple large-area pop rivet (with the mandrel pushed out) as a static port. Vans Aircraft spent a lot of time years ago determining the location, appropriate size and protrusion of the port. Trust me: You are not smarter than Van.

Some builders have expressed the desire to have a flush-mounted static port in their RVs (to mimic a Cessna I guess), only to find that in most cases this introduced an error into the system, and many ended up gluing a pop rivet head over the flush port to bring the system back into calibration.

Builders also like to try and improve the pitot tubes. Again, most of the time, changing the stock design will result in some error in the system-though it can be argued that, perhaps ironically, the pitot tube is a bit less likely to cause gross errors than changes from the recommended static port. Incidentally, if you find yourself cast into these waters by a kit maker that doesn’t offer a specific static-system design, its recommended that you borrow concepts from existing aircraft. Look at how Cessna and Piper have done it over the years.

The issue with pitot-static errors is that you may not even be aware they exist. Your airplane may stall very slow or cruise very fast compared to your peers based on indicated airspeeds that could be in error. Many aircraft designers spend lots of time in the early stages perfecting their pitot-static systems (using complex instrumentation and hardware that we as builders simply do not have) to provide the most accurate system available.

Leaks = Errors

There are two main sources of problems we usually find when doing pitot-static checks on aircraft (both certified and Experimental). The first being connections between various instruments, and the second being the connection to the instruments themselves. In older airplanes, a common source of leaks occurs where many planes joined metal tubing from the wing with flexible tubing in the fuselage via simple connections such as a piece of rubber hose with safety wire or zip ties around it.

Aside from the obvious changes to a system such as using completely different static ports or pitot tubes, there are other ways that errors may be introduced into your system, the most predominant being leaks in tubes or fittings. To understand how leaks can happen, lets take a look at how most systems are plumbed.

Method 1: Rigid aluminum tubing. In decades past, this was almost the only way to hook up pitot-static systems, as plastic or nylon was not yet prevalent. While it is possible to do a good job with rigid tubing, it can be difficult to work with, requiring heavy AN style fittings as well as flares on the tube at each joint that are time-consuming to do. Also, rigid tubing is not conducive to a clean, flexible and easy-to-use system from a mechanical and maintenance standpoint. The counterpoint is that aluminum tubing does not decay, is well-proven, and we know it works.

Method 2: Modern plastics and nylon tubing. Various types of tubing are available to homebuilders. Offered under numerous brands and trade names, the most common type is Tygon or nylon tube that is semi-rigid in form, meaning that its somewhat flexible, but still rigid enough to keep from collapsing on itself. The size most frequently used is 1⁄4-inch OD (which is 3⁄16-inch ID) for the main portion of pitot-static plumbing. This has become the de facto standard for modern aircraft.

When it comes to the fittings themselves, once again a large variety is available in the marketplace-though it is almost certain you will be dealing with an eighth-inch NPT (national pipe thread) fitting on the instrument or EFIS box. Some builders choose to use simple barbed hose fittings, but many times those are difficult to work with; it has been our experience that with this combination it is difficult to fit and maintain a good seal. It was popular for a while to plumb with softer surgical tubing, but we do not recommend using that either.

A Fitting End

Up the chain of quality from the simple barbed fittings are 100% plastic compression fittings available from many suppliers in various configurations. Again, this method has been used with success, but the joints can start to leak. Some of the low quality threaded fittings use all plastic components that work fine when new, but over time can become misshapen and cause a leak. The preferred threaded fittings will have some sort of metal ferrule, compression sleeve or a good quality rubber O-ring to complete the seal.

One thing to remember when installing these types of fittings is that over-tightening them can cause damage, which is just as bad as under-tightening them. Also, pay attention to whether the type of fittings you use require some sort of sealant or Teflon tape. Typically, the nylon fittings do not require tape or lube-in fact, using thread tape will work opposite to your intended path, making the threads indistinct and actually causing leaks. Teflon paste is OK for these fittings-but take precautions to keep the paste out of the instruments. Seriously! All-metal fittings, aluminum or brass, should absolutely have either Teflon tape or paste. But never use silicone-based thread compounds, as these will contaminate your expensive instruments-ask me how I know.

Push, Don’t Shove

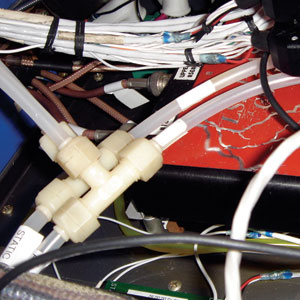

Method 2A: Most current fittings are the newer push type. These allow for quick and easy insertion and removal of the tubes, and they help you do a clean job of plumbing your system. Some of the various fittings available help you to simplify multiple daisy chain type runs of tubing in favor of a simple manifold. These fittings are readily available. (Disclosure: SteinAir sells these fittings, but they are available from such sources as SafeAir1, Avery Tools and McMaster-Carr.)

One important aspect if you are using these fittings is to make sure there is a firm seat when you insert the tube into the connector. When you push the tube in you may feel that it is seated and connected, but you must push firmly to a second detent to fully seat the tube into the connector. Its also imperative that the cut end of the tube be square and flat (don’t use scissors to cut it). It’s also important to use the proper tubing when using the newer style push connectors. If you use tubing that is too soft, it will not seal. While we are on the subject, another trick is to use one color of tubing for the pitot and another for the static system. This may seem somewhat trivial until you remove an instrument that has two white tubes sticking out of it, and then try to determine which was which when reinstalling it. Anyone who has done much work on instrument panels will appreciate color coding.

Making the Connection

The last area of importance in the pitot-static system is the connection to the back of the instruments. This is where we often find leaks while checking pitot-static systems. As mentioned, the common size for fittings on the back of instruments is eighth-inch pipe thread. If you are plumbing multiple instruments together as many homebuilders do, it’s often easier to use a manifold instead of routing lines from one instrument to another. The manifold can be positioned where convenient, and separate lines may be run from there to each of the instruments.

Even if you elect to use threaded instead of push-on fittings, manifolds can be found that make your task simple. Visit an online supplier such as McMaster-Carr and search for manifold. Aircraft Spruce & Specialty also sells aluminum manifolds with a variety of port sizes and configurations. You’ll find many options for distribution of your pitot and static lines, and you’ll have much less of a mess.

No matter what style of tubing or connectors you choose, there are a few other items to remember when installing the pitot-static system. First, make sure that static system has the ability to drain water out of it. Because most static fittings are located relatively high on a fuselage and much of the tubing can run below that level, it’s easy for moisture and water vapor to become trapped. Use a water trap, or route the tubing in such a way that there are no low spots where water can collect. A perfect example is the way the static ports on each side of most RVs are interconnected, with another tee fitting slightly above the ports that runs forward to the instrument panel. In this case, no trap is needed because the static port itself is the low point.

Don’t forget that even though the plane is Experimental, you’ll still need the requisite FAA inspection on the system for IFR flight. This should be accomplished by an FAA certified shop or individual with calibrated equipment. You can test the system for leaks yourself before visiting a professional by simply connecting a piece of surgical tubing to your pitot tube or static fittings and either squeezing the tube or hooking a syringe to it to apply pressure or vacuum. Care in the selection and installation of your pitot-static system, will give you instrument accuracy, safety and confidence.