With a newly minted airworthiness certificate in hand, new worlds of flying excitement beckon. This is, you remind yourself, a big part of why you undertook the project in the first place. Here is your reward—if not all of it, at least a substantial part.

But before we get too carried away applauding our efforts, we must deal with the serious business of making the first flight. Too many airplane builders wreck their planes on the initial flight or shortly thereafter, and I did not intend to join their ranks. Apprehension and uncertainty always accompany such endeavors. However, to the extent possible, surprises need to be eliminated beforehand, which means lots of unexciting checking and planning.

The Designated Airworthiness Representative (DAR) gave us a punch list of minor but important things to do. A few bolts had too many or too few threads showing and needed to be replaced. All of the inspection covers needed to be put back in place, and we needed to fix our one real bonehead mistake—not putting drain holes in the fabric in all the places that could trap water. We completely forgot all of them, but at least we were consistent. A half hour with a soldering iron and that problem was solved, but it was kind of embarrassing.

The Jabiru 3300A engine provides more power with less weight than the Continental O-200 also offered with the Texas Sport Cub kit.

Preparedness Reigns Supreme

Before the big day a little pilot preparation is in order. I have some basic requirements for a first flight that I have picked up from the EAA material on the subject and my own experience. Here are the major items on my list.

I want someone who had nothing to do with building the plane and with trained eyes to check everything over for anything we might have missed. It is so easy to simply overlook something when you have been working on a project for months or years. The DAR brought two A&P mechanic friends with him, so that got handled.

Fuel problems bring an inglorious end to many first flights, so checking fuel flow ranks high on the preflight priority list. We placed minimal fuel in the main tanks, set the plane up in about a 15° nose-high attitude, disconnected the fuel line going into the fuel pump, and timed how long it took to drain a quart of fuel. Ideally, this test should show a fuel flow that is about twice the full-power fuel needs of the engine. I was looking for a quart of fuel to flow in about a minute (15 gallons per hour).

Switching the insurance from builder coverage to flight coverage is another big item to handle before the first flight. Be aware that some companies exclude coverage for first flights. In my case, I found that Avemco had the best deal for the project insurance I wanted during the construction phase. However, the company would not convert that policy into one that covered first flight. Prudence sent me to SkySmith and AIG for flight coverage.

Author Prizio (left) and building partner, Ed Zaleski (above), are happy with the outcome.

Good weather is important for a first flight. With a new taildragger that means light or no wind, especially no significant crosswind. Good visibility and plenty of room under the clouds round out what I call good first-flight weather. The idea is to minimize challenges and distractions that divert attention from basic flying.

Yes, it comes with air conditioning. Windows and doors on both sides of the cabin can be opened in flight. Watch your headset during slips!

Having flying skills up to par ranks high on the priority list. With some hours logged in the factory demo plane I felt pretty comfortable with the handling of the Cub. It is simple and handles predictably if consideration is given to its light wing loading. Three hours of dual in a Citabria a few days before the first flight got my brain in taildragger mode, even if the much heavier Citabria doesn’t really feel much like a Cub.

Lastly, I want to have a Plan B if something goes wrong. In other words, where the heck will I put this thing if the engine conks out? Chino Airport is surrounded by a number of farm fields, offering large flat spaces fairly well suited for an emergency landing. The one negative is that many have furrows that are perpendicular to the runway heading. I did some rough calculations of my critical altitude numbers based on what I expect the plane to do. At Chino (elevation 652 feet) I should be at 1100 feet by the end of the runway. At that height I have enough altitude to make the 90° turn to land with the furrows. Up to about 900 feet I can get back on the runway straight ahead with a hard slip. Between 900 and 1100 feet I am going to probably have a pretty rough landing against the furrows, but at least there are no large obstacles to hit. By 1300 feet I should be able to safely make a 180° turn back to the airport. By having these options in my head before I go, I have already made the decision about what to do if the engine fails.

Behold the electric Cub. The Dynon FlightDEK-D180 EFIS/engine monitor is the centerpiece, flanked by a Garmin 496 GPS with XM weather, a Garmin SL40 com and a Garmin GTX 327 transponder.

One of my good flying buddies, CFI Richard Eastman, says the more prepared you are to deal with trouble the less likely you are to encounter it. His logic is that the very act of thinking through and planning for problems gets you to do things that are likely to eliminate or at least reduce the severity of those potential problems. I hope he’s right. With a nice clear, calm Saturday morning presenting itself and an airplane all signed off, inspected and ready to go, it was time to go flying.

Taxi Time

The plan was to begin with a high-speed taxi test to evaluate handling before actually leaving the ground. If that went well, I would take a short flight consisting of a climb to 2500 feet, some slow flight to the edge of a power-off stall, and then a return to land and check things out. I rolled out on the runway, applied two-thirds power, and raised the tail. The 120-horsepower Jabiru engine accelerated the Cub quickly, very quickly. Before I realized it, my taxi test had turned into a flight test, so I chopped the power, eased the nose up, and let it settle back down for a three-point landing.

The Cub passed the taxi test with no handling problems, so I figured I might as well move to step two: planned flight. With full power, the plane leapt into the air and climbed like the proverbial homesick angel. I swung out wide of the normal traffic pattern, climbed to a safe altitude, and slowed it down to the edge of a stall. Everything felt great. I called the tower, headed back for a respectable landing and taxied back to the hangar. What a rush! There are few things more exciting than a first flight in a new airplane you built yourself.

If the cabin looks smallish here, imagine what it would be like had the Texas Sport Cub not been built around a fuselage cage some 4 inches wider than the original.

As the flight-test period proceeded, problems quickly emerged with cooling. The cylinder-head temperatures were uneven and a bit high on the rear cylinders. This was somewhat expected with the Jabiru engine. Baffles in the plenums for each bank of cylinders must be trimmed to balance airflow and thus cylinder-head temps. This is just a cut-and-try process that each Jabiru engine must go through. I also ended up replacing the needle jet in the carburetor with a richer jet to get mid-throttle EGTs in line with factory specs. The Jabiru engines use a single Bing carburetor, a bigger version of the carb that’s paired up on the Rotax 912, and it has no manual mixture control. However, you can affect idle-speed, midrange and full-throttle mixture by changing settings on the carb—idle mixture through a screw, the needle for midrange and the main jet for full-throttle/high-power.

The high oil temperatures I was experiencing proved tougher to solve. I installed a larger oil cooler, put a lip on the exit of the cowl and redid a number of things to help air flow through the oil cooler, all with minimal improvement. Calls to both Jabiru and Texas Sport were answered with supportive sentiments but little that actually helped—there are times when you, as a homebuilder, are really out there on your own, and it’s up to your patience and persistence to get the problem solved.

Did I mention persistence? During a casual conversation at Sun ’n Fun, the Texas Sport guys asked me which dipstick I had in my engine, to which I replied, “The one you sent me, of course. Why do you ask?” Further conversation revealed that I had a dipstick for a level engine (tricycle gear) installation that was leading me to overfill the engine with oil. After getting that sorted out and removing a quart of unneeded oil, the temperatures dropped 25°. I now have a happy engine. According to the FAA, an Experimental/Amateur-Built airplane is meant to be a source of education and recreation for the builder. I hope the education part of “education and recreation” is finally getting near the end. Let the recreation begin!

One thing that I decided to change was more related to my specifications rather than any deficiency in the airplane. After a number of hours flying around with Cub-like legroom, I just couldn’t take it anymore. At 6-foot-3, I found the Cub a bit too tight, so I modified the front seat to gain 2 more inches of room. What a relief! I can now fly for 2 hours without needing a chiropractor to extract me from the cockpit. I also had to modify the rear control stick to clear the pushed back seat, but that wasn’t difficult.

An afternoon’s flight over the rolling hills east of Chino…a more than suitable reward for the building process.

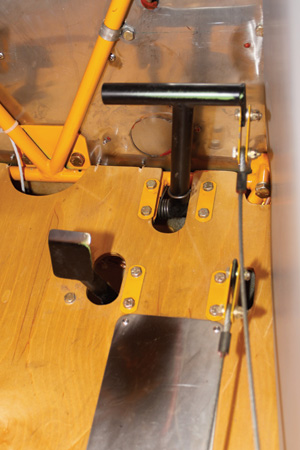

Heel brakes were common when the Cub was new, and they’re reproduced here, albeit with much better brakes at the other end.

In Retrospect

It’s worth looking back at the process and reviewing what went well and what could have gone better. Let’s start with the good stuff. I love the plane; everyone does. I got, well, actually the airplane got called beautiful three times on the first two flights. How cool is that?

The kit components, with the exception of the fiberglass parts, are first rate and actually fit with little special effort. The improvements that Texas Sport has made to the original Cub design are really nice. I did not appreciate how nice until I sat in an authentic J-3.

The portions of the assembly manual that are actually complete are pretty good, with lots of color pictures. The people at Texas Sport are nice and friendly. I never had to coax them to let me fly the demo plane when I was there, and they let me ask their people questions and poke and prod things to my heart’s content. They always provided me with the information and parts I needed, and they never quibbled about sending me a part when I said it was missing.

The things that didn’t go well can mostly be traced back to poor documentation and paperwork. There is no doubt that American Legend/Texas Sport knows how to build Cubs. They have built more than 150 of them, and overwhelmingly people are happy with them. What they are slowly coming to grips with is that knowing how to build an airplane and explaining how to build an airplane are not the same thing. This problem is solved during the builder-assist program by having knowledgeable people standing right there to explain. For kit builders, however, that is not an option. The company is making progress on improving the manual, but as of this writing there is still work to do.

The lack of a proper wiring diagram and proper labels on the instrument panel caused me a fair bit of grief. The Dynon FlightDEK-D180 included in my panel was defective, but trying to decide if it was the Dynon unit itself or the indecipherable panel wiring took a lot of extra time. Once we figured everything out, Dynon cheerfully and quickly fixed the unit under warranty, but there was more than a bit of steam coming out of my ears by the time it all got sorted out.

Traffic nine o’clock high. Wingroot fuel gauges are part of the Texas Sport Cub’s simple approach. You’ll find the trim indicator in the left wingroot along with the ELT and ignition switches.

Using the factory builder-assist program would have eliminated all of these problems, and I would recommend it to anyone who really wants to get one of these planes and still have most of the experience of building. However, some of us just want to do it ourselves. We had to drive around the airport too many times looking for a Cub to see how something was supposed to fit together because the assembly manual didn’t cover it. The silver lining in this little cloud was that it forced us to interact with other Cub people, which was an unexpected pleasure in almost every case.

In the end it all boils down to one question: Would I do it again knowing what I know today? The answer to that has to be yes. We learned a lot, not all of it what we expected to learn, but that’s OK. The airplane came out really nice, and there is something magic about a Cub, even if it isn’t exactly a real Cub. No one seems to care about that. The experience of working through things we didn’t anticipate is where the most valuable learning took place and where we had some of our most satisfying encounters with other Cub owners. I will be a much better EAA Technical Counselor because of the experiences I had building this airplane, and we have a really nice airplane to fly. What else could you ask for?

For more information, call 866/746-6159 or visit www.txsport.aero.