I thought I would close out this build series on the ’Beater by sharing some lessons and overall experiences. If you remember, it all started when I mentioned to Carol that I might like to build a helicopter, and she replied by stating perhaps I should learn to fly one first. As usual, she had a good point. So I did just that, starting in a Robinson R44 for about 10 hours and then completing the training and achieving a commercial rotorcraft rating in the Hughes T-55.

I thought I would close out this build series on the ’Beater by sharing some lessons and overall experiences. If you remember, it all started when I mentioned to Carol that I might like to build a helicopter, and she replied by stating perhaps I should learn to fly one first. As usual, she had a good point. So I did just that, starting in a Robinson R44 for about 10 hours and then completing the training and achieving a commercial rotorcraft rating in the Hughes T-55.

Just doing all the training was in itself a pretty good undertaking. After 11,000 hours of fixed-wing flying, learning the new skills required for helicopter flying was both intense and greatly satisfying at the same time. I still wanted to build a helicopter, so I continued to pursue the best options and within six months of completing the flight training I was drilling holes and riveting on the Hummingbird. I did make a promise to myself that I would stay proficient during the build process, as it is very easy to lose newly acquired skills without regular practice. So, I kept the T-55 until about six weeks prior to flying the Hummingbird.

Keeping the T-55 was expensive, no doubt, and I constantly wrestled with keeping it. I kept trying to justify that I could just go rent a helicopter, and perhaps it would be cheaper, plus give me some extra room in the hangar. However, renting helicopters is very expensive and the SFAR 73 requirements for PIC of an R44 are pretty stringent. On top of that, I am not aware of one helicopter flying club!

I also told myself that there was one other reason to keep the T-55, as there was one common operating feature between it and the Hummingbird that I thought was important—neither of them had a throttle governor. The R44 did have one. I really liked the governor, as once the throttle was twisted open, you could feel the governor take over and move the throttle grip to the proper operating speed. The throttle in a helicopter is at the end of the collective control, which is in your left hand. The throttle requires constant monitoring and adjusting, primarily during hovering, liftoff and touchdowns, to not overspeed or underspeed the engine. It’s one more control that takes some time to build muscle memory. Once you are in cruise flight it doesn’t take as much adjusting. In fact, for 90% of cruise time I usually set the friction lock on the collective to keep it in place. Sure, you can turn the governor off in the R44, but mostly we didn’t.

So, while the cost of keeping the T-55 was not exactly cheap, I think it paid off in the long run. I was able to stay proficient and had gained about 170 hours of flight time before I made the first flight in the Hummingbird.

Focusing on Maintenance

Another valuable skill I gained while owning the T-55 was a true understanding of the maintenance requirements compared to fixed-wing aircraft. During my time in the Air Force, I worked on UH-1s and CH-3s as an avionics technician, even getting to fly in them. I didn’t spend any time around the crew chiefs, which would have helped me understand how much maintenance went into them, although I did notice that it seemed we canceled more helicopter missions than we did C-130 or U-2 missions. Most of the equipment back then was older, so I assumed age was a factor.

How wrong I was! Owning the T-55 helped me understand all the jokes about helicopters trying to shake themselves apart and being nothing but massive hydraulic leaks, etc. I’ve always talked about building for maintenance and reliability, and I think the T-55 helped me understand how to do that in the Hummingbird. I won’t repeat some of the things I’ve shared with you in prior columns, but now that I have crossed the 100-hour mark, I’m starting to gain some confidence that with the right approach, the helicopter can be just as reliable as a fixed-wing aircraft.

However, the big difference is that reliability in a helicopter comes from not only building it properly, but making sure you have the right focus on the maintenance. There’s no doubt that maintaining a helicopter requires a whole new level of discipline and time commitment. I know there are some who can quote the ratio of maintenance to flight hours on various aircraft, but I really don’t keep track of that. I do know that whatever the ratio is on my Hummingbird, it is all worth it when we can go to dinner and back with no problems. For me, completing the trip to Oshkosh—requiring over 22 hours of flight time—with no problems made it fun. Albeit long.

Hummingbird vs. RV-10

If you just sit back and think about the differences between the RV-10 and the Hummingbird with respect to moving parts, it can be inundating. On the RV-10 there is one engine with no transmission connected to one spinning constant-speed propeller. The only lubricant required is engine oil since the MT propeller requires no periodic lubrication like the Hartzell prop as an example.

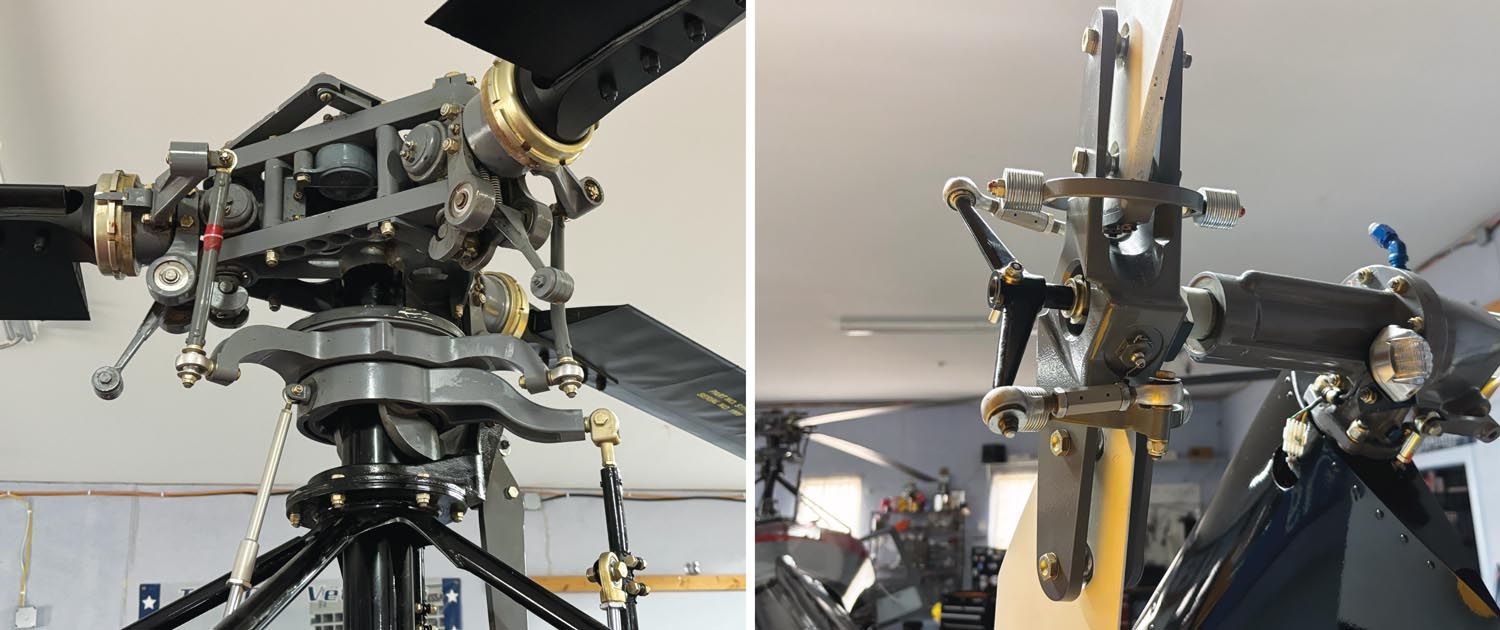

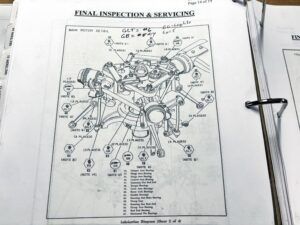

Now compare that to the Hummingbird. The engine is connected to a centrifugal clutch, which has bearings in it that require lubrication. That connects to a transmission, which powers the main rotor and the tail rotor driveshaft. The transmission has its own oil sump requiring a different oil than the engine. The tail rotor driveshaft connects via couplings to the intermediate transmission at the end of the tail boom, passing through seven bearings all requiring periodic lubrication. The intermediate gearbox has its own sump and connects through a driveshaft to the tail rotor gearbox. It, too, has its own sump. The tail rotor is fastened to the tail rotor gearbox, with the tail rotor having two Zerk fittings and four bearings that require periodic lubrication. Oh, did I mention that the main rotor hub has over 40 different lubrication locations!

For the RV-10 I think I have one type of grease and that is used for the wheel bearings. For the Hummingbird, I have at least five different types of grease and two or three different types of oils and spray lubricants. I had to buy about three more grease guns when I reached final assembly.

While I try to not think about all the moving parts between the engine and the rotors while flying, it clearly does take more attention to maintenance. The maintenance manual is very good, clearly explaining the time interval requirements and types of lubricants for the various parts. Personally, I think it is good to have a little OCD when it comes to owning and flying a helicopter. The maintenance takes time, and a good part of it is a greasy, dirty job. I’m lucky that my hangar is at home. An hour or two every few days is all it takes to keep the Hummingbird clean and well lubricated. Of course, I’m a little OCD about the time intervals and perform all of them at much smaller intervals than recommended. It gives me peace of mind, and with it being a new aircraft I can get an early read on wear items.

Now, lest you think I am complaining about owning a helicopter, I am not. Learning to fly a helicopter and then building one has been a very wonderful experience overall. I’ve learned some new skills with regards to both flying and maintenance, and I’ve found sharing the helicopter to be just as much fun as sharing fixed-wing flying. I’ve somewhat limited the sharing until I reached 100 hours in the Hummingbird, and now I intend to open that up some more. The view from helicopter is more birdlike since most flights are between 500 to 1000 feet. There’s more observable detail. In Carol’s words, “One gets to see a whole lot more for a whole lot longer!”

Do I think helicopters can be as reliable as their fixed-winged counterparts? I think it’s possible, but it does require a whole lot more maintenance and attention to detail. I don’t think the same capabilities are there, such as long-distance travel. As an example, I initially thought it would be wonderful to fly the Hummingbird to Alaska. There are so many places along that route that we’ve often commented how nice it would be to land, which is quite impossible in the RV-10. But even in the RV-10, the round trip to Alaska is over 50 hours. The same trip in the Hummingbird could easily take two to three times that. I think the maintenance requirements for a piston helicopter such as the Hummingbird would just put too much of a damper on the fun factor. A turbine helicopter is out of the question for me says Carol, so we will stick to flying the Hummingbird locally and to a few fly-ins and use the RV-10 for the long trips.

Hopefully we will see some of you at Sun ’n Fun in the spring. Yes, we are planning to bring the Hummingbird. That should be fun!

See you & Miss Carol there…