The dream. Lifting off in a small, form-fitting craft. The machine behaves perfectly, just as you expect it will. The machine responds to every nuanced action as if it is reading your mind. The machine blends with human interaction perfectly. The air flows quietly over the polished surfaces, lifting you higher, faster, according to your desire. The engine sound is reassuring and smooth. There is no apprehension, no fear, as you are carried effortlessly into crystal blue air. Leveling off at 1000 feet, you marvel at the effortless performance and intimate response of this small airplane. It’s a dream.

The dream. Lifting off in a small, form-fitting craft. The machine behaves perfectly, just as you expect it will. The machine responds to every nuanced action as if it is reading your mind. The machine blends with human interaction perfectly. The air flows quietly over the polished surfaces, lifting you higher, faster, according to your desire. The engine sound is reassuring and smooth. There is no apprehension, no fear, as you are carried effortlessly into crystal blue air. Leveling off at 1000 feet, you marvel at the effortless performance and intimate response of this small airplane. It’s a dream.

But this isn’t a dream. It’s the real thing, so perfectly matched to the dreams I had over and over again, falling into fantasies of flight every night. By day I would labor in the garage, assembling the aircraft and thinking about how it would behave in the air. More importantly, how would I feel? As a new pilot with few flight hours, could I possibly arrange a situation where I didn’t feel fear and apprehension on my first flight?

When you look for the perfect airplane for yourself, you want these expectations to line up with reality. With a little help from my friends getting dual in the Pulsar and a thorough test plan, I could combine the dream with reality. In fact, reality won out over the dream.

Today, the Pulsar remains a fond memory for many. And while the design is no longer in production, there are occasionally unfinished kits surfacing, and there are, according to a recent fleet-size estimate by KITPLANES® contributor Ron Wanttaja, just more than 100 still registered. (There were more than 150 as recently as 2009, but the FAA’s move to a triennial re-registration process has culled what are likely to be non-flying examples from the rolls.)

So the question is: Is the Pulsar for you? Here’s what you should know.

Flying Impressions

What attracted me to the Pulsar in 1995 was the size and well-proportioned appearance. It looked like the sports car I always wanted. Sleek, light, fast. My logical brain kept telling me to research more than one airplane kit; as I went about that delightful task at Sun ’n Fun, I couldn’t help returning to the Pulsar booth.

The wonderful thing about this airplane is that it flies the way it looks. I personally thought that Mark Brown must have designed the airplane specifically for me; at 5 foot 7 and 124 pounds, it was. The surprise came when I attended the Pulsar builders’ group event in Kansas to see 6-foot-plus,185-pound men jumping into Pulsars. But that was the attraction; you slip it on and then unleash it.

Because the aircraft is small and light, it sips mogas at the rate of less than 4 gph at 135 mph cruise. The baggage carrying capacity is deceptive; when I and a companion went to the shows and camped out, we got everything into the plane, including the six-pack of beer. We were right at gross weight, it’s true, but the airplane didn’t care, retaining its impeccable handling throughout.

Performance

You might surmise that I enjoy a light, responsive aircraft. You’re right. In addition to that anti-gravity wrap-around feeling, the Pulsar performs across its entire bandwidth. At a claimed empty weight of 460 pounds for the 582 model and 510 pounds for the 912 model, you can understand how quick these airplanes are with any of the efficient Rotax engines. Amazingly, the owners with the Rotax 582 (two-stroke, 66 hp) engines still obtained a cruise only 10 mph less than the XP 912 (four-stroke, 80 hp).

Even with new-builder empty weight creep, the airplane performs with vigor. If you go Pulsar hunting intending to buy, don’t be surprised at empty weights of up to 630 pounds. Between applying too much fiberglass resin to layups and adding an IFR panel, weight creep is fairly normal. You’ll just need to decide how much you want to fit in the airplane when you fly, especially on trips. When I built mine, I added 20 pounds of soundproofing foam to the cockpit before upholstery; it was a deliberate trade-off. Gross weight on the Pulsar XP is 1060 pounds; however, several builders told me they “tested” the aircraft to higher loads, so some data plates show higher gross weights.

One hallmark of flying behind the Rotax 912 is that you don’t need to think about fuel mixture. The dual Bing carburetors are self-compensating at altitude. A free-castoring nosewheel along with high outward visibility make taxiing a delight. The canopy can be left open until run-up on hot days. The Pulsar gets off the ground quickly and climbs at 1200 fpm after getting free of the ground in about 800 feet of runway.

Once in the air, you feel that you’re in a larger aircraft. The handling is stable with linear pitch and roll response. Light rudder gives a predictable change more in yaw than roll. With stall at less than 50 mph, you can mush along all day at 65 mph for air-to-air photos and sightseeing, or at 150 mph when you’re trying to get someplace fast. While Vne is 160 mph, you lose fuel economy traveling over 145 mph.

The tapered wing (loading for the XP is 13.25 pounds per square foot) produces lower drag and makes for a very stable cruise. The differential Frise type aileron system reduces any adverse yaw for no-surprise turns.

Stalls are docile and predictable. When the airplane stops flying, it will tell you with a gentle wing drop, easily brought back to level with some rudder and power. In turns, roll is progressive and stable. Aerobatics? Don’t even think about it. With an airplane this slick, you will drill yourself into the landscape. The Pulsar includes a No Spins placard.

Like takeoffs, landings make you look good. Full flaps make for the best sight line. The mechanical flap lever is at your left hand with up to 40° of deflection. Even with stall speeds of 45–46 mph, it’s best to keep a bit of power on over the fence above 60 mph. The landing gear has some spring to it and feels solid as you land, with no tendency to overcorrect or bounce. It acts like a magnet once you’re on the ground. It’s easy to hold the nose off as you slow, and the front tire arrives at the surface naturally. The Pulsar can also handle hard and “mistake” kinds of landings, but they are unnerving. On one cross- country I made early in my Pulsar flying adventures, I landed sloppily and was convinced that the gear had sprung so far that it punched holes in the underside of the wings. I got out to inspect it at the FBO, expecting the worst, and everything was perfectly fine.

On a cross-country, you can routinely expect fuel burn of 3.5 to 4.2 gph at 75 to 85% power settings. This gives the Pulsar XP bladder-stretching ranges of 4–5 hours over 600-plus miles with a mere 20 gallons of mogas.

About the Design

Pulsar designer Mark Brown was a purist. While all aircraft are designed to be light and energy-efficient, simplicity is scarce. Starting with a very specific vision makes the design easier to execute. Mark knew he wanted to begin with a craft that wrapped around a human body, so that dream we all have of lifting off into the air with almost nothing around us becomes a reality.

The Pulsar was purposefully built to be small but capable. I compare it to the Mazda Miata in the automotive world. The Miata doesn’t haul lumber and isn’t designed to. A Ford station wagon isn’t meant to delight through the gears on corners. The Pulsar does exactly what it is supposed to do. In other words, it’s a sports plane and not a 172.

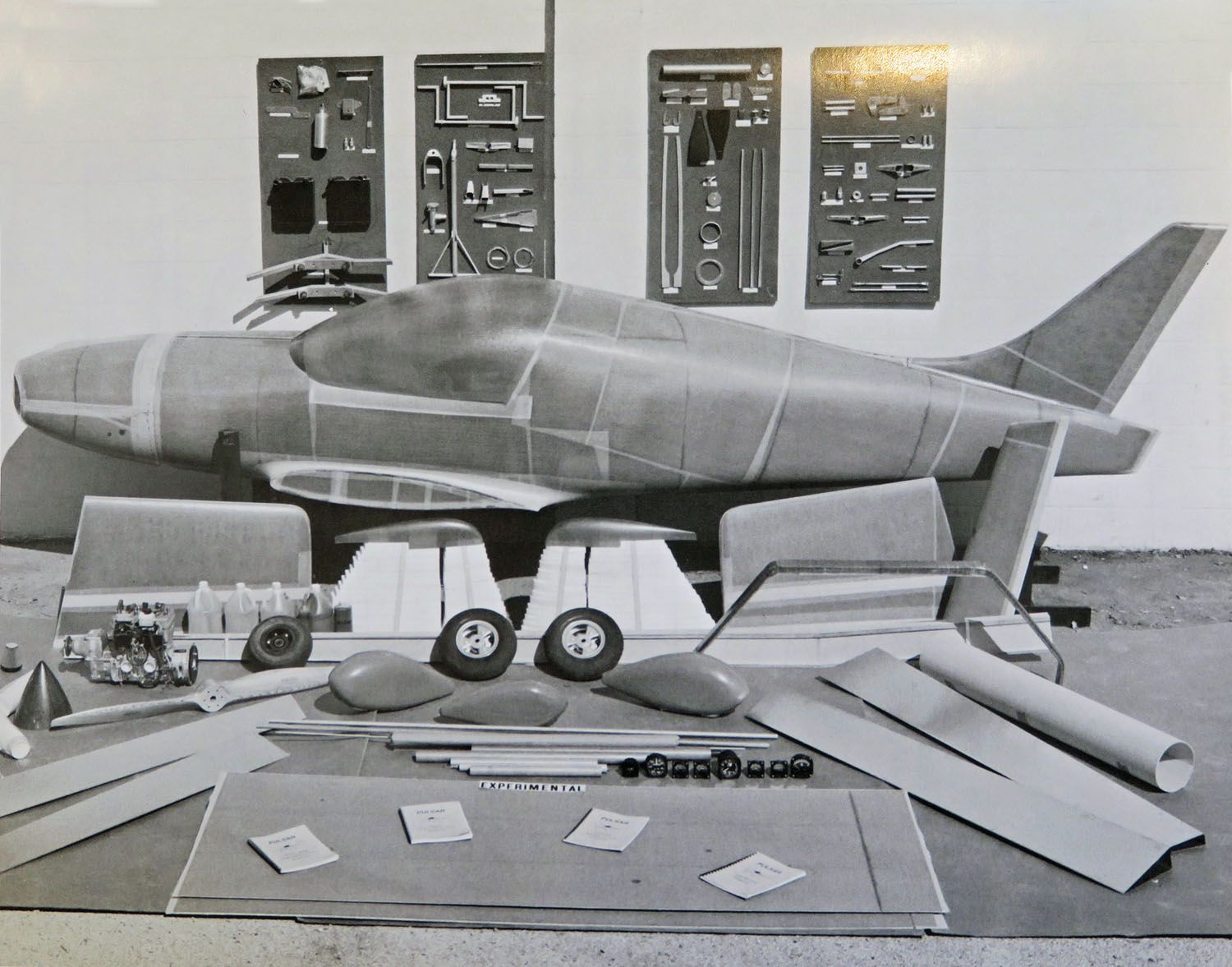

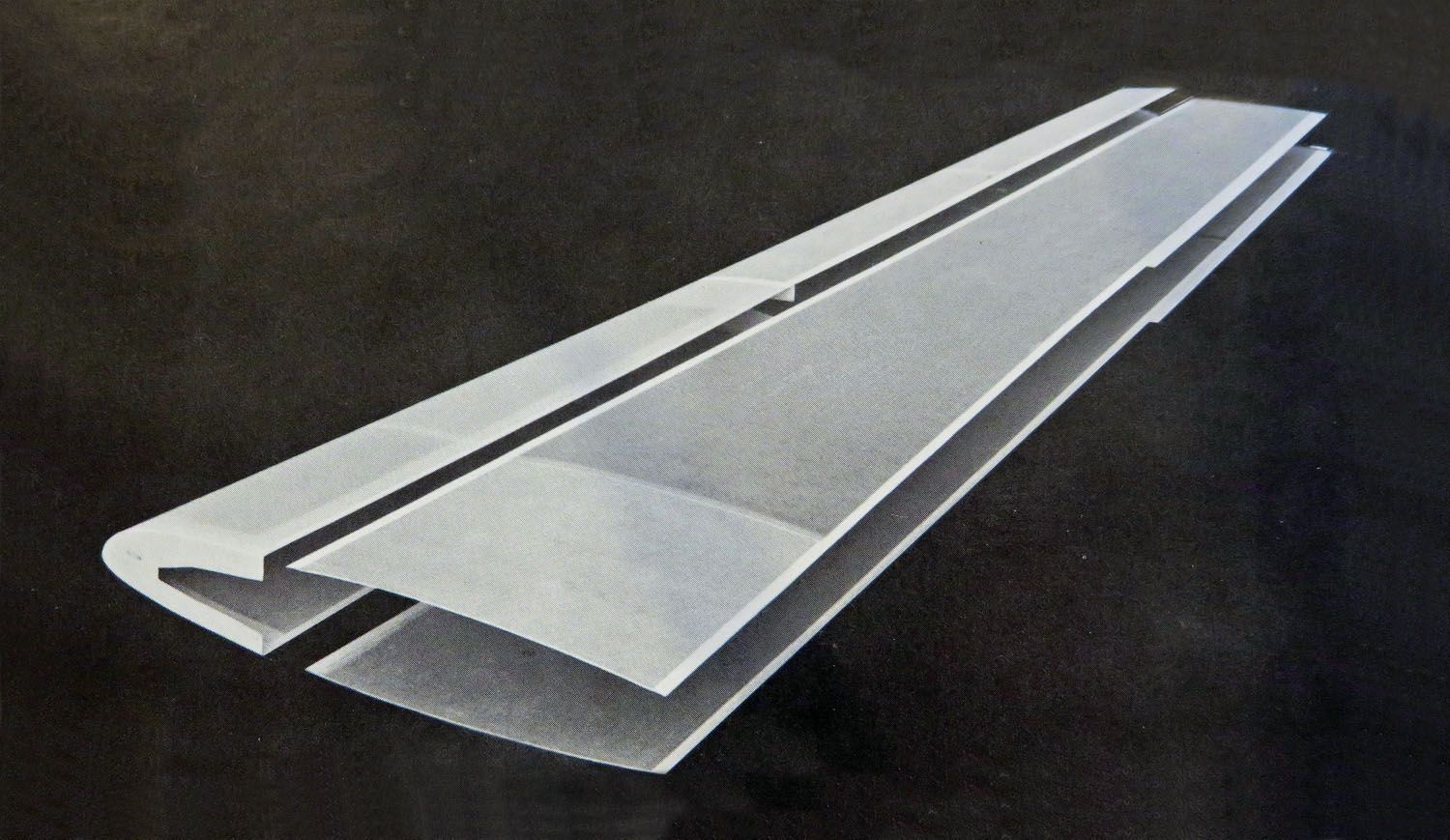

The first Pulsars used foam-core sandwich construction (pre-preg molds) throughout the fuselage and a factory-manufactured composite spar for the wings. Aluminum fittings for attach points were integrated into the spar during manufacture. The birch plywood in earlier model wing skins were replaced with composite pre-cambered skins. Wing ribs were precut extruded polystyrene. Spars overlap the entire fuselage width for effective loading and use 5/8-inch shear pins that can be pulled for wing removal. (Fun fact: the right wing is slightly ahead of the left wing because of this spar overlap. The wing structure is symmetrical, with the same distance from the leading edge to the spar on both wings.)

In the Pulsar 582, the fuel tank is in the forward fuselage. In the 912, two separate tanks occupy the leading-edge D section inboard for a total of 20 gallons. The canopy is a simple slide-forward one-piece design using three tracks built into the fuselage. Landing gear is factory-molded unidirectional glass construction. Many a pilot will tell you they were amazed to survive very hard landings with this gear. On the early tricycle-gear versions, the nose gear was delicate and easily damaged if a pilot landed front first. In later models, a tougher nose gear was added.

The cockpit is cozy and comfortable once you figure out how to get in—slide in from the seat feet first. The rake of the seat—35°—is good for both visibility and comfort and a clever way to accommodate taller pilots. When the Pulsar is being assembled, the builders usually arrange everything to fit themselves since there are few adjustments that can be made later. Rudder pedals, along with heel brake levers, are fixed where the builder puts them. If you purchase a Pulsar, you can adjust the fit by removing or adding seat cushions.

Early models came with cable-actuated band brakes on steel drums. Matco hydraulic units were an option that many builders chose. Some pilots disliked the heel brakes. I was one of them. I designed toe-brake levers to go into the heel lever pocket, and it worked well. It also afforded a little more leverage, so stopping took very light pressure.

The arrangement of the throttle on the left side of the panel with a flight stick forward of the center console works well for comfort and control and makes for a simpler control system overall. (Remember that simpler is almost always lighter, and designer Mark Brown usually chose lighter over heavier.) The armrest alignment means you only need light stick pressure to control the aircraft. It also obviates the need for dual controls. Originally, pitch trim was a lever ahead of the center console, low and under the panel. Many builders fitted electric trim with a switch on the stick.

Brown smartly designed a shock-mounted instrument panel for the Pulsar. Because he wanted to keep visibility high through the front, the panel doesn’t stare you in the face but sits low. For me, this was a selling point. The rub (literally) is that the panel height doesn’t allow much stretch at the bottom if you want to add extra space and get your legs underneath it. Despite the size, with an additional inch or two of panel height, I was able to fit a full panel of instruments for IFR flight. Used Pulsars today can be fitted with the smaller glass displays. The panel can be demounted for work behind it, but accessing the wiring bundles as they disappear into footwell corners is not as easy.

Because of the low cost of the kit and its simplicity, the Pulsar did not come from the factory with many options. You could add a side window (Lancair style) and hydraulic brakes. Some pilots added an auxiliary fuel tank. The airplane came with a GSC ground-adjustable two-blade wood propeller—56-inch for the 582 and a 60-inch for the 912. You could add an optional in-flight adjustable-pitch propeller.

Values Today

Living in today’s Experimental aircraft environment and looking back at what we actually paid for a kit decades ago is startling. I paid about $25K for my Pulsar, and that included a new Rotax 912 engine. I spent another $12K on instruments, upholstery and paint. Four years later, I sold the airplane for over $10K more than I paid for it.

Typically, you go into the building process expecting to fly out of it with what you put in materially with no profit margin. Your labor is considered a freebie on resale. This ends up being a great deal for used homebuilt buyers.

In the last 10 years, however, this has changed dramatically for popular aircraft—Van’s RV series is an example. Builders are getting more money—sometimes a lot more—on resale than what they put in. It’s simple supply and demand.

So when you’re looking for a tried-and-true used homebuilt, the prices can be all over the map. The original prices you see below don’t mean much now if you are looking for a Pulsar, but it does give us some perspective.

In the early 1990s, the 582, complete with engine, could be had for less than $18,850. After interior and paint, most builders spent less than $28K to get in the air. The most popular used Pulsar choice now is the 912-powered XP because of engine durability, economy and performance. The used prices depend on condition, hours and accessories. The range is from $35K to $65K, simply because the maintenance and quality of storage over time is highly variable.

Later Versions

So far, we’ve talked about the early Pulsars, the 582 and the 912-powered XP. In 2001, when the Super Pulsar 100 was introduced, the kit cost was about $27K, not including the engine; an estimated completion cost was about $65–$85K. If you find one for sale now, you’ll likely see prices between $65K–$90K depending on the engine and condition. For more, see the sidebar below, “Pulsars Through the Years.”

If a complete or partial Pulsar kit is in your sights, do your research. After the XP, there were so many name changes that you need to understand what you are actually getting and if you’ll be able to find parts for it. If it looks like a complete kit, expect to pay from $10K–$16K, not including the engine. If I were looking for another Pulsar, I would look for the most complete kit I could find.

What model Pulsar are you buying? After SkyStar sold the Pulsar rights, there were Pulsars in different stages of modification. The Pulsar Aircraft Corporation changed the design of the XP by enlarging the cockpit and modifying the empennage, naming it the Super Pulsar 100. Then they decided to offer the small Pulsar again, but with different engine choices. Suddenly, there were different airframes with four different engine options.

What to Look For

If you are looking for the Pulsar 582 or 912 XP models, check the serial numbers for vintage and talk to the builders’ group. The very early Pulsars (see “Pulsars Through the Years” sidebar) had some teething problems. Band brakes and solvent-dissolvable foam (the blue polystyrene) wing ribs come to mind. The mid-1990s XP model is, in my opinion, the sweet spot for the “sports car” economy version of the Pulsar. It was manufactured between 1992 and 1999. Look for hydraulic brakes (Matco) and brown solvent-resistant wing ribs.

Find a qualified person to do a thorough prebuy on any Pulsar you fall in love with. They should be familiar with the vintage you are considering and be able to identify model differences. Once again, it’s a good idea to check with the builders’ group.

If you find a complete kit, thank your lucky stars. Yes, there are some complete Pulsar kits out there in garages, storerooms and attics. Most of them are minus an engine, which may be a good thing. An engine that sits for decades should be overhauled for inspection and time-limited parts replacements. But if the price is right and you perform your due diligence, it could be a fantastic deal. Make sure you are getting the chain of ownership paperwork, the manuals, and the parts list.

The Pulsar builders’ group still exists and has fly-ins every year in Kansas. We’re a friendly bunch and have made many replacement parts, upgrades and mods to our Pulsars. What we love most is the camaraderie around our airplanes, an unexpected but most welcome benefit. You will not be disappointed.

Photos: Mike Fizer, Lisa Turner, Marc Cook.

Here’s another one for the history department: In the late 1990s, HK Aircraft Technology AG of Germany took the Pulsar XP, did some major modifications and then tried to get it type-certified as the Wega 100. The project ended when the second prototype crashed in 2001 after entering a spin in stall testing, killing test pilot and company owner Hans Keller. The first prototype was probably written off after an EFATO ending with substantial damage, also in 2001.

https://abpic.co.uk/pictures/view/1326713

Thanks for the article.

I loved the Pulsar Super 100 for a long time and would love to own one. (Maybe I’ll luck into finding one, either as a kit, or already built in a few years, after I retire.) I only looked at the Super 100 because I have broad shoulders and know from flying 172s that 39″ of shoulder room isn’t enough for me.

I hadn’t realized the KIS-TR4 became the Super 100. That opens up the possibilities a bit.

On a sad note, if I remember correctly, Solly and another person were killed in a Pulsar when it crashed in the Andes a number of years ago. That’s the reason Pulsars are no longer produced.

This is a fantastically well researched article. I owned a pulsar XP about five years ago. The aircraft came from the Boulder Colorado area and it was flown out to Florida by a gentleman I met it was retired 747 check ride pilot for United Airlines. Don’t know how you fit his 6+ foot body into the aircraft but got it down in a few days and helped me with transition training for my insurance. I came from a late model Cessna Skylane 182 with you 1000. And I can tell you that except for size inside the cockpit, it was a fantastic airplane and honestly I felt like I was getting away with something flying 120 to 130kts at 3.5-to-4 gph. I have some hastily filmed YouTube videos of me for line along the coast in Jupiter, Florida and over Lake Okeechobee Florida on YouTube. Look for Pulsar XP Florida and you’ll probably find them.

For those of you that are over 510, this is going to be a very tight aircraft to fly into unless the seats been modified. I barely had enough room with my headset on to fit under the canopy. I used to sit on a quarter inch piece of foam. But the reclining seat angle made it quite comfortable despite the lack of padding. This was a very nice plane to fly with great manners.

The weak link in my opinion was the front nose gear landing gear. I had a front wheel work that cracked all the way through without a prop strike. But it was also difficult to keep the Belleville washers tight enough on the castering nose wheel. Also, the 912 version had class in gas tanks. They were a wet wing and they leak. Especially if they’ve been burning out of gas which has ethanol in it. I had a weeping wing in my aircraft that was an issue.

Somehow I ended up talking myself into buying a Taildragger and saw the Pulsar to a Canadian who flew it back to Vancouver Canada. I also had the pleasure of meeting the original builder and his son years later in Winter Haven Florida when I had the aircraft up for sale. They got a real thrill seen it still flying with close to 700 hours on airframe and engine.

I’m back in the market for another aircraft. Not sure if I’ll buy another low wing. Probably will end up with a Luscombe tail wheel aircraft. But this was a great chapter in my flying diary.

Dean, thanks so much for your observations. I love your comment about “getting away with something” – I had the same feeling, as if it was too wonderful and too magical to be true. But every time I jumped in that airplane it was, indeed, magical. Although I wanted to move on to other kits, and did, I miss the Pulsar magic.

Such a fantastic design and time of posting July 2022 , there is no factory support or parts kits sold I’m puzzled why is this the case 🤔 see the odd used built one or 2 for sale but not like numbers of a Jabiru

Right, exactly; this is what happens when companies stop producing a model or go out of business. Fortunately, the builders group is still robust. But I agree; if you’re looking now probably better to choose a modern era kit with support unless you want numerous challenges with a Pulsar kit. Thanks, L

I have a Pulsar XP project for sale. Have kept it in my basement for 30 years. I have the Wings and fuselage kit. Contact Evan for pictures and information.

Did you sell your Pulsar kit?

Hello Lisa,

Nice post and nice your Pulsar.

I am building a new experimental in Mexico and I am looking for a caster nose landing gear fork like that at the Pulsar.

Where do you recomment to look at?

Best regards

Hi, Evan. Can you send me a email of your project?

I’m looking at a partialy complete pulsar that is a tail dragger.

I want to know if it’s easy to change to a tricycle undercarriage from the tail dragger design before the build goes any further.

Thanks in advance

Michael

Hi Michael,

It’s not easy but it is possible. I’d contact the builder group to get advice.

Lisa

Hi.

Apologies for butting in on your excellent article about the pulsar.

I have have a Rotax 582 early mark. To get it to flying condition, all I need is a canopy. I have been trying for many months to find one To no avail. I hope someone could advise me on where to obtain one. It is such a shame that a beautiful new looking aircraft is languishing under a tarp in the back of my hangar.

Regards

John