One of the classics in the very light airplane category is the CGS Hawk, but the surprise is how conventionally it flies by “real airplane” standards—that’s not a backhanded compliment, it’s a full-on atta boy!

Two radiators flank the engine, plus carburetors on the right, exhaust on the left, prop in the middle.

The Hawk was originally designed by the inimitable Chuck Slusarczyk, one of the pioneers of the early days of powered hang gliders (think Easy Riser) who started Chuck’s Glider Supplies, whence the “CGS” in CGS Hawk. He was also on the TV show Junkyard Wars…twice. Also his was the notable, noxious, notorious, non-aeronautical liquid concoction called “Muzzleloader,” a secret combination of paint removers and rocket fuels frequently foisted off on the unsuspecting as a liqueur. In my case, a quarter teaspoon years ago was a lifetime dose. Slusarczyk calls this rite of passage into the CGS world a “liquid dignity remover.”

Slusarczyk’s shop manager for 10 years, Charles Capaldi, moved from northeast Ohio to southwest Alabama with CGS when it was sold recently to Danny Dezauche, a longtime ultralight pilot and Hawk owner, who after years of discussions with Slusarczyk, bought the business (whose name remains CGS Aviation). Dezauche says he bought it because, “The EAA chapter was the kind of people you want your kids to be around,” and his boys are 10 and 14.

The view forward is terrific with the small, low windshield. And, no, the mirror is not for avoiding bird strikes from the rear.

Multiple Models

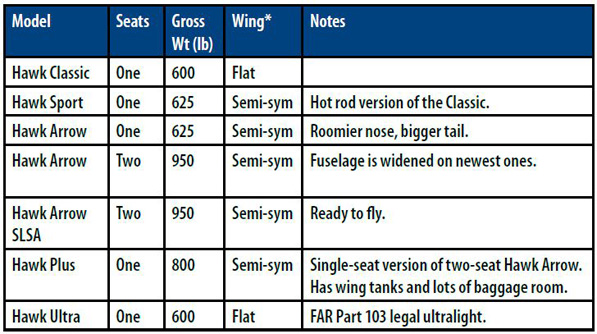

The Hawk line has been in full production for six months now at the new location, and there are a half-dozen versions (See Table 1).

Table 1. *Note: Flat wing is flat-bottom airfoil, and there are jury struts on the wingstruts. Semi-sym is a semi-symmetrical airfoil with no jury struts.

Taildragger and nosedragger versions are available, and there’s a flight school coming to teach you how to fly your own Hawk. The ultralight Hawk Ultra weighs only 244 pounds empty, so it will be possible to make a nosewheel version that is still Part 103 legal (254 pounds or less).

The covering applied to any of these models can be either sailcloth or Poly-Fiber, your choice, with speeds and handling qualities reported to be about the same for each covering type. Wings with the Poly-Fiber covering have an aluminum leading edge under the fabric, but sailcloth wings do not. The Classic and Ultra (as in ultralight) models have a flat-bottom airfoil with no rib holding the bottom surface, but the rest have structure to shape the bottom contour. The airfoil is a CGS0012, and it is unlikely to be found in any of the traditional airfoil texts.

The plexiglass in the doors provides great views of the ground, and each occupant has two air vents for cooling.

All Hawks have a curved, tubular aluminum tailboom that’s bent in a humongous tube bender at the factory. To make sure the doublers fit, they are attached to the boom before it is bent.

The ubiquitous Rotax 582, but an older model. Also seen are the radiator cap and the BRS ballistic parachute.

Bensinger’s Baby

The particular aircraft we flew was built by Hawk dealer Steve Bensinger from Bushnell, Florida, about an hour north of Lakeland. His aircraft has the Rotax 582 engine, the older version (model 90) of the familiar blue head (model 99). For the four-stroke crowd, the 60-horsepower HKS 700E engine is available, and a handful have been installed on the two-seaters. A large battery up front keeps the weight and balance under control. Bensinger is looking forward to the 700T, a turbocharged version with 80 hp (for takeoff) and only a little more weight. The ubiquitous Rotax 912 has been installed by one customer, and the factory is working to make that an option once the center of gravity issues are resolved.

Bensinger’s Hawk has had the wing expanded by adding one more rib and one more bay between ribs to each side, increasing the span from the stock 31.5 feet to 34. (Single-seaters have a 29-foot, 10-inch span). The flaps were extended as well, but the ailerons stayed the stock length. (All of the Hawks have separate flaps and ailerons, not flaperons). Optional wing fuel tanks, 5 gallons per side, replaced the standard 10-gallon fuselage tank.

Ailerons have spades, just like the hot rod competition aerobatic designs. Don’t get your hopes up, though. The Hawk is a great cruiser but not an aerobatic ship.

All Aboard!

Entering the front cockpit requires its own unique technique. You stand in front of the right wingstrut so that you don’t have to clamber over the throttle on the left side, then lean back along the wingstrut and stick your left foot in as if you were feeding an alligator but wanted to retain a few body parts for yourself. The rest of you sort of follows your foot onboard. Once in, there’s good room all around, but you don’t want to bonk your head on the emergency parachute handle overhead.

Electric start is not only a convenience, but a safety factor. “Safety, safety, safety” was Bensinger’s comment on the matter, and I was reminded of another pilot earlier in the week who buckled his passenger in, then stood on the ground beside his plane so that he could get enough leverage to pull-start the two-stroke engine.

Rudder and elevator cables emerge from the tailboom to do their duty. The very top cable actuates the trimtab.

Takeoff from the grass ultralight field involved a series of bumps and moderate acceleration, not at all like some of the overpowered single-seaters. Heading into the sun, I could not read the MGL Avionics Stratomaster instrument cluster, perhaps because my sunglasses were incompatible with the display. Not knowing the pitch attitude, I was faster than the desired climb speed of 60 mph. Not to fear. Bensinger got the speed under control with pitch attitude until it was time to level off at the 400-foot pattern altitude.

Leaving the pattern, we headed past South Lakeland and climbed, being rewarded with smooth air at 1200 feet. That smooth air was moving, though, with about 30 knots of winds aloft. The Hawk’s handling qualities were some combination of sailplane and airplane, with a yaw string out front to indicate sideslip. With a skid ball, the memory aid is “step on the ball,” but with a yaw string, you step to pull the string toward that foot. It’s not that hard (glider pilots do it all the time), but the process is a bit different and slightly confusing if you don’t do it enough. Yaw string notwithstanding, banked turns of 10°, 20° and 30° were easy, with a nice, light, smooth feel to the ailerons. Predictably, the roll rate with the longer wings and stock ailerons was slow to moderate, but the yaw string was easier to control than in, say, a Schweizer 2-33.

The rudder attachment atop the tail boom.

One surprise was the amount of indicated sideslip you can generate with the rudder. With the yaw string taped to the forward fuselage instead of on a mast, the amount of deflection is not necessarily an accurate measure of the sideslip angle (the horizontal angle between the relative wind and the direction the airplane is pointing), but it was impressive to see the yaw string showing more than 30° of sideslip.

Conventional Handling

With the aluminum-tubing fuselage, the oversized plexiglass doors, and the yaw string and the pusher configuration (not to mention the wing loading of 6.7 pounds per square foot), you’d not easily confuse the Hawk with a “real” airplane in the narrow sense of the term. But flying the Hawk required less accommodation than other aircraft derived from ultralights. Most of that was predictable, such as adverse aileron yaw and the need for rudder, just as it is for other low-speed airplanes.

These “real-airplane” qualities were apparent in the stall performance as well. Stalls were preceded by a light buffet, and the nose fell through with the airplane having little tendency to fall off on one wing. Departure stalls were perhaps the mellowest that I’ve ever seen in an aircraft, with a gentle break and the nose dropping only a little.

The exhaust and ballistic parachute close up. The left wingtip and tail of the Hawk Ultra are visible behind.

One unique interruption to this handling qualities exploration was an insistent flashing red light above the compass. I asked if it was a warning that we were lost, but Bensinger explained that it was a warning for high exhaust-gas temperature from the two-stroke engine. The remedy for high EGT in a two-stroke is to put some load on the prop, which means climbing or maybe a turn.

Speaking of which, turns had their own quirks. In a 20° bank, you could hear the engine load up, and the airspeed dropped from 72 mph to 65 mph with the added induced drag of the turn. With the high winds at our altitude, the ground track of our turns seemed more like a prolate cycloid than a circle.

Back to the Barn

The view from over the area south of Lakeland was a hodgepodge of metal, with mobile homes and ranch buildings, and shanties sharing the real estate with McMansions as we went to South Lakeland Airport for a landing or two. Still, this kind of sightseeing is what low and slow is all about. The real gotcha is that in case of engine failure, low altitude and a poor glide ratio limit your options for forced landing sites. This Hawk did have a ballistic parachute installed, but ballistic ’chutes are not necessarily the answer to every emergency, because if the landing gear doesn’t absorb the vertical deceleration of a landing under canopy, your spine will. The Hawk gear is fiberglass, and there’s crushable structure around it, and those features would increase survivability.

Bensinger did the first landing, flying the pattern at 60 mph, with me adding two notches of flaps when requested, using the flap handle over my left shoulder. The trick in flying a very light, high-drag airplane was explained to me years ago—fly to the runway, fly down the runway, then land. Bensinger landed right on centerline, then added power and away we went.

My approach started high, but an extended downwind took care of that. Then a thermal and a bit of wind shear on short final messed with me. Even so, control was easy and my touchdown was also on the centerline. The gear, which had felt so stiff taxiing out, felt just right on the landing. Full power got us back in the air, and by now I knew the pitch attitude for climbout, retracted the flaps to the first notch, and headed us back toward Lakeland.

The ultralight version, the Hawk Ultra, flies overhead at the Sun ’n Fun fly-in last spring. You can fly it Part 103 even after losing your FAA medical. (LSAs can be flown with no medical or an expired one, but not after a denial.)

The Hawk Ultra on the scales. At 244 pounds, there’s 10 pounds available for a nosewheel or whatever else the Part 103 pilot might desire.

The Paradise City traffic pattern is this huge affair that is usually, but not always, under the helicopter traffic pattern. Final is at least a mile long, and you lose altitude slowly. Plus, there’s a little more pressure when landing in a frisky crosswind in front of a few hundred spectators and a narrator who seems to know everything about every plane out there. But I forgot and gave the stick a tug in the flare and ballooned like a newbie. Fortunately, the Hawk was easy enough to control that I recovered and touched down on the upwind wheel first and gentle as you please, just like all the books say to. Nice.

With Chuck Slusarczyk semi-retired, it’s great to see his designs still flying, still in production and still supported. This is a neat little machine, and deserves the following it has. Four-stroke engines will make the Hawks even more attractive to a Sport Pilot who’s downsizing from bigger aircraft. Even without a snootful of Muzzleloader.

For more information, call 251/957-HAWK (4295) or visit www.cgsaviation.com.

![]()

Ed Wischmeyer is an AirCam owner and has flown about 175 makes and models—from the CGS Hawk to the Thunder Mustang—with more than 100 pilot reports published. All of them just about paid for his most recent rating: the ATP/AMES in a Grumman Widgeon.

Dear sr. Excuseme for my english.

In the CGS HAWK 2, THEre are same place for some baggage?

Thanking you in advance

M. Grandjean

Is a fuselage covering Covering available for Hawk classic single seat Thanks

How does a CGS Hawk Arrow II owner become flight check endorsed on a Hawk Arrow? Where are A&P certified technicians sourced?