I logged my first official instructional flight on June 17, 1975, at age 15. I already had my private and an instrument rating before I ever used a proper aviation headset. All those years and hours without realizing that those overhead speakers that I thought were normal had the speaker cone equivalent of a paper bag. I was was working on my commercial rating when my dear wife bought me a shiny new David Clark H10-80 headset, which was the pea-green flagship of the iconic company at the time. Its heralded technological advancement was that the previously chromed parts were painted black to reduce glare from the sun.

The time finally came to try the new headset out in a real airplane. Since our steed for the day had been built without an intercom or push-to-talk switches, we borrowed the FBO’s portable kit that consisted of a bag of plug boxes and myriad cables and PTT switches to attach to the yokes with hook-and-loop strap. It took a while to set up, but in the end it was worth it, at least for the first hour or so.

The airplane was eerily quiet. ATC was crystal clear and my instructor no longer had to yell, which didn’t stop him. Into the second hour, however, the clamping pressure was taking its toll and the headset seemed to be gaining weight as we went along. As with any new experience, I kept fidgeting with it to get it where I thought I wanted it, especially in and out and up and down with the mic.

By the third hour, the headset had morphed into a demonic vise and must have gained ten pounds. My head, neck and shoulders all ached. A severe headache seemed to cross my eyes. I was so ready to be done with this flight and to get this angry octopus off of me.

During the debrief, my instructor, still bearing the visible impressions of his headset around his ears, handed me a couple of Excedrin and assured me that one gets used to the experience over time, which I found to be prophetic, because I have had a love/hate relationship with that headset for over 4000 flight hours. I still own it, quietly tucked away in a box in my closet somewhere.

As my career progression continued, I did grow to adapt and appreciate that headset, especially when opportunities arose to fly real airplanes that had real intercoms and real PTT switches. Before long, all I needed was to temporarily remove the headset and hear the naked roar of unprotected flying to wonder how I ever got by in the overhead speaker days. Time passed and before long I was the chuckling CFI introducing my own students to the angry octopus. Times were changing in aviation and I never let any student fly with me without a headset.

Say Again?

The first time my headset became a lifesaver instead of a mere convenience item was when I got my first airline job flying Fairchild SA227 Metroliners. The “Metro” is powered by a pair of Garrett TPE331 turboprop engines, which are legendary for the profound way they turn money into noise. Since my airline was in the process of changing livery, my class’s new-hire flight training consisted of ferrying aircraft to and from St. George, Utah, to a paint shop in Mena, Arkansas. Going out, we took a flagship Metro III, and the noise between those Garretts was only merely deafening. Coming back, we had the pleasure of strapping on a vintage, much louder Metro II. To further accentuate the sonic overload, the particular beast we were assigned to for the next several hours had had its entire interior stripped out to the bare metal, which seemed to focus the noise directly at the cockpit. It wasn’t a noise that you merely heard. It was a multidimensional experience that you felt throughout your body. It hurt your lungs as you breathed. We wore those expanding ear plugs in addition to the David Clarks, but even then the volume was pegged at 11. Working closely sandwiched between those two angry turboprop engines was a sonic experience akin to taking a large Zildjian cymbal off of a drum kit and slowly cutting it in half on a coarsely bladed table saw.

Was That For Us?

A few aurally painful years later, I hit the lottery and landed a position flying Boeing jets. Jets may be noisy on the outside, but the cockpits, compared to what I had been used to, seemed wonderfully quiet. In those days, the most common headset was the venerable Plantronics MS50/T30. The guts of the unit where both the mic and the earbud connected to were actually quite tiny, not much bigger than a piece of Chiclets gum. It was just big enough to have a clip on each edge to somehow position the unit near one’s temple for proper positioning of the hollow tube mic in front of the mouth.

Glasses wearers were in luck as the unit could conveniently clip to the arm of most glasses. Another option was presented to us in new-hire class. A lady from a local hearing aid company came to class one day and using a turkey baster sized syringe, shot our window side ear canals (right for first officers, left for captains) full of some kind of warm quick setting goo that would harden after a minute or so. From those molded blanks, the shop would fabricate a plastic custom in-ear earpiece with a tube embedded for the audio connection instead of the standard rubber nipple. Attached to the earpiece was a flat plastic stick to which the headset itself could clip on. That molded unit served me well for a few years until captain upgrade class when the lady returned to repeat the process for the other ear.

As we each waited for our turn, a classmate ahead of me yelled out in pain and when the lady pulled back the syringe, his ear poured blood down his neck. (True story.) I decided at that moment to bug out of line and become a glasses clipper from that point on.

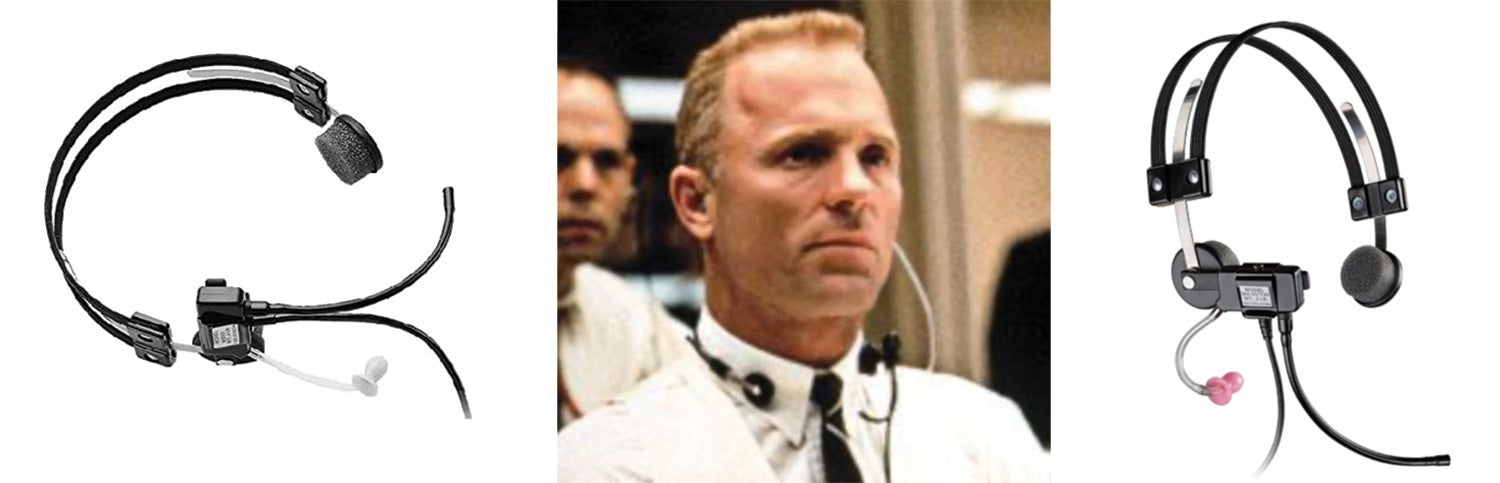

One other option to secure those Plantronics headsets to one’s temple was a rather Rube Goldberg-ish double-bridged/lightly-sprung headband/temple-pad contraption with the requisite plastic stick on which to clip the unit itself. These headbands were included with the units but rarely used. It was common to find those cursed headbands abandoned in several odd nooks and crannies around the cockpit. I never once observed any airline pilot using that get-up as intended, although I’m sure we all tried it on once just out of curiosity.

Amusingly, when the movie Apollo 13 came out, actor Ed Harris (portraying Mission Commander Gene Kranz) was seen sporting the Plantronics headband situated around his neck with the mic upright in front of his mouth and the ear nipple attached to a comically long piece of aquarium tubing to reach the ear. Curiously, I did see a couple of fellow airline pilots try to recreate that application of the assembly—to limited success that mostly looked ridiculous in the cockpit environment.

In preparation for this article, I wasn’t sure if wearing the head assembly around the neck was actually a NASA thing or just that some producer/actor just didn’t read the instructions and jacked it up, so I asked our resident NASA expert, Paul Dye, and here was his answer: “It was a mark of experience to wear your headset in a creative way, and the truth was, you couldn’t wear that headband on your head for eight hours … so around the neck with an extension tube for the ear piece was common. I wore my Apollo-era headset clipped to my glasses for decades. Everyone did something different, and no one wore them the way Plantronics expected.” Kudos to Hollywood for authenticity.

Today, active noise canceling headsets are the thing. One of the first active noise cancelling headphones for mass market general public use was the Bose QC2. An entrepreneurial pilot designed and produced an apparatus called a UFly Mike, which plugged into the QC2 and turned it into an extremely nice and convenient aviation headset package that for a time was very popular with airline pilots, myself included. Unfortunately, that option came crashing to a halt airline-wise over some convoluted politics and turf battles mostly centered on TSO certifications and battery issues. UFly still makes terrific products at attractive prices for general aviation aircraft. I have a Bose/UFly combo headset at each passenger seat of my RV-10 and they are very well received.

Another headset innovation of sorts lately are the headband-less in-ear models like Clarity Aloft. I bought my wife a Faro Air, which is similar to the Clarity Aloft and she really likes it. Most of these types attenuate noise passively by using expansion foam type earplugs encasing their tiny speakers. Bose makes an active noise cancelling version called a ProFlight 2 that looks like something that RoboCop would wear. The headsets without headbands are often popular with ladies who don’t want to muss up their hairdos and some male pilots that don’t want to molest their tender hair plugs as they set root.

A few years ago, Bose came out with its A20 noise canceling headset. They aren’t cheap, but they are well made and strongly backed. They come with or without Bluetooth capability which can be used for music and/telephone input. Of the dozen or so headsets I have used over three decades, the Bose A20 is my favorite hands down, both in the Boeing and in the RV-10. The sound quality and noise attenuation are both stunning. I do have to add that there are some disadvantages to ultra high end sound fidelity, however. Boeing missed the memo on voice-activated intercoms so their decades-old system is either always on, always off or temporarily switched on via yoke switch which most pilots are too lazy to do. That makes always-on the most commonly used mode and combined with ultra-high fidelity means a sonically intimate experience with your crewmate as in every gap-toothed whistle, every hummed tune and every gastro-intestinal uplink (still preferable to GI downlink) in ultra-high fidelity. After a while considerate types learn to raise the mic away from their mouths before a cough or sneeze. Enough said.

One last word on a high-end headset with music input. Listening to music while flying is a grey area with varying opinions on both extremes. Obviously there are times when it is totally inappropriate even though most of the headsets that facilitate the option also have the feature to mute the music input when an intercom or ATC reception is received. There are other times, for me at least, when it is wonderfully, shall we say, not inappropriate. Opinions obviously vary, but my opinion is if you have to ask, just don’t do it.

Out of the blue, I have recently returned from another wonderful Flying Samaritans trip to Baja Mexico. (See “A Good Samaritan,” May 2018). Coming back from the clinic in López Mateos, to where we overnight at Mulegé, I love to divert slightly east and sightsee over scenic Bahía de Concepción. It was nearing sunset and absolutely gorgeous, and the experience was transformed from merely lovely to absolutely sublime with the addition of “Riviera Paradise” by Stevie Ray Vaughan. In this moment, the music was perfectly appropriate.

Any way to convert the Plantronics MS50 (“Apollo”) for use with a standard headphone jack or bluetooth?

Interesting article. In particular, the DC H10-80 model, which I have not heard of.