As builders, we are generally good at doing the research: reading directions, poring over plans and diagrams and generally trying to figure stuff out ahead of time. We are not, however, always top-shelf when it comes time to heed what we learn, but sometimes that’s for good reason.

I have a specific example. When I installed the Dynon EMS-D10 into my GlaStar, I knew that I wanted to have fuel-flow measurements; they’re a great piece of the diagnostic puzzle plus it’s nice to know how much gas is on board, especially if it can be to a high degree of accuracy. Certainly more accurate than the wiggly mechanical gauges I have.

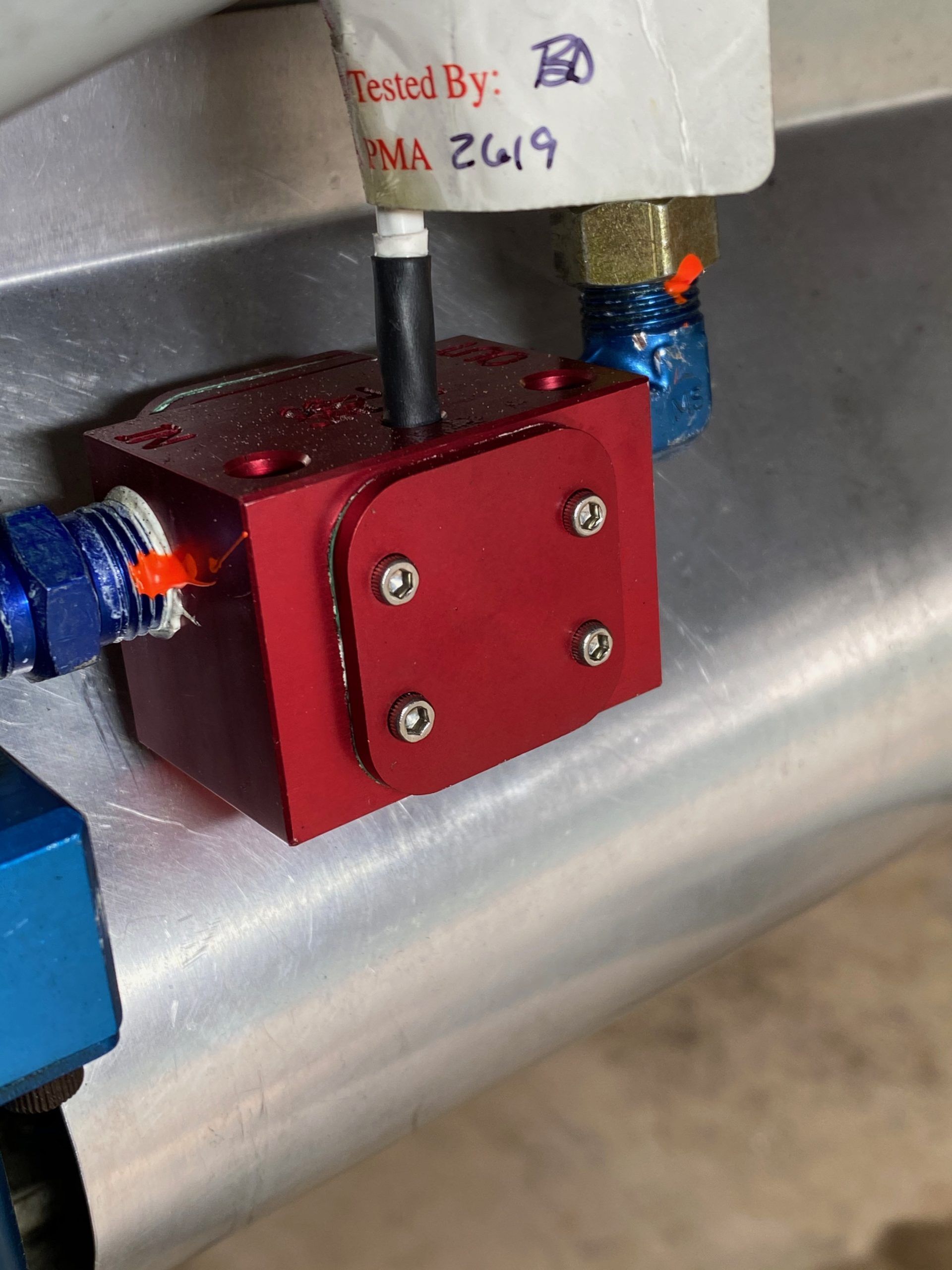

As part of the engine-monitoring package, I ordered the so-called “red cube” fuel-flow sender, which is made by Electronics International. It’s become the standard in homebuilts because it’s affordable and durable. The mounting instructions are necessarily a little vague because firewall-forward details are so variable in our world. The red cube works with fuel injected as well as carbureted applications, and there are even versions of the sender meant for high-wing aircraft (without any fuel pumps) that depend on pure gravity feed.

In my application, I have high wings and no boost pump (for now) but the O-320 does have a mechanical fuel pump in the usual location on the accessory case. Supposedly, there’s enough head pressure from the high tank location to keep fuel flowing in the event the mechanical pump fails. It’s something you test before first flight, which I did not commit on this particular airplane.

There are many possible options for mounting the red cube that should put it in the flow path, enough to get a reading at least. One I chose was a pure, unadulterated expedient. In the GlaStar, the main fuel system penetrates the firewall low on the passenger side and hits the gascolator first. Then a long hose runs to the fuel-pump inlet just to the pilot’s side of center. Another short hose connects the fuel pump outlet to the carburetor inlet; all very neat and tidy.

My first attempt was to intercept fuel flow at the gascolator output, which meant easily mounting the cube and substituting a few AN fittings. It was easy—too easy. It’s worth noting here that EI says the cube should be between the last fuel pump and the carburetor (in that case) and, in the case of a fuel-injected engine, between the servo and the flow divider. What I had built up wasn’t strictly what was called for, but—and here is where you can drive off the rails—other builders have tried a similar approach and reported “success.” I figured that since I had all the parts on hand, it was worth a try.

The Dynon EMS did register a reading that mostly made sense using the baseline K factor. If you haven’t used a fuel-flow module before, you should know how it works. Basically there’s a small wheel that is spun by the fuel flowing through the box. The wheel converts this motion into electrical pulses, which is what the engine monitor interprets. The more flow, the more pulses over time. You can calibrate the entire system by adjusting the so-called K factor, which converts pulses into volume inside the instrument. Phew.

I thought I was home free, but I did notice that a few readings in flight didn’t “make sense,” based on what I would have expected from this engine. Over the next few dozen flights, every time I filled up (at the same pump, to the same level in the tanks), I would record the difference between what the airplane consumed and what the instrument said it should have. At first, it was far off, and I worked by changing the K factor to bring it in line. I thought I had it sussed when I noticed that the indicated readings had swung the other way; where it over-stated fuel flow before, it was wildly understating it later. I found myself chasing accuracy with the K factor and quickly losing confidence in the outcomes. Plus, I could influence the readings by switching to one tank, which you get to do in a GlaStar because getting both tanks to feed evenly is an ongoing challenge.

Clearly, Electronics International knew of what it spake. I also found comments from EI support staff that basically said they weren’t 100% sure why but any location other than the recommended one probably would function but probably would not be accurate. The unasked question was: Are you willing to work at it for accuracy? I noted a few builders’ comments that said, essentially: no. They’d take lower accuracy for ease of installation. There are plenty of these transducers running around installed like mine or even in the cabin ahead of the gascolator.

Unfortunately, I’m not wired like that.

If the box were to go where it was intended, I needed at least one new fuel line. Truth is, I’m not conversant enough in building my own hoses these days—it’s been more than a few years and I no longer have several of the important tools, plus this is the fuel system, which I respect greatly. So I took a few measurements, went onto the Aircraft Spruce site and ordered a new fire-shielded hose. I was able to re-use the existing pump-to-carb hose, so I only needed one. It arrived less than a week later, made by TS Flightlines, and it was perfectly built and exactly what I asked for.

Now, where to put the cube. I had originally planned to build a small shelf riveted to the firewall because there wasn’t a good way to hang the transducer off the engine where it needed to go. (Also, because EI absolutely does not want this sensor bolted directly to the engine, so splicing it in right at the fuel pump outlet or the carb inlet wasn’t an option.) After noodling it a little, I realized I could fabricate a simple bracket and Adel-clamp it to the engine mount; the fewer firewall penetrations the better, I always say.

Results? You bet. After just a few trips to the gas pump and some minor adjustments to the K factor, the difference in calculated and actual consumption closed dramatically and remained consistent. My experience with this sensor, albeit on an injected engine, was that it could be made very consistent from tank to tank, typically off by no more than 1-2%.

It’s true that I had somewhat predicted the outcome before I’d started, based on the research I’d done, but there was a substantial body of evidence to suggest I would not be happy with the outcome. In my defense, I had all the parts to test the “easy” way before having to purchase a new fuel hose, and it seemed worth doing. You know, for science. But, in the end, doing what I knew was right turned out to be the ultimate solution.