Sometimes, when using shorthand in our conversations about Experimental aviation, we use the term “barriers to entry” primarily in the context of money. And it’s true. Aviation is expensive, always has been. The industry is small, the pilot population is minuscule (around 660,000 pilots in a population of 330 million) and the ability to amortize investment over a large number of units is almost nonexistent. We get weak in the knees when more than 1000 new aircraft are delivered in a year, which is about how many 4Runners that Toyota loses track of each year. And it’s also true that aviation requires a high level of commitment, from the wanna-be pilot and the actual pilot as well as from suppliers in our sphere.

Those are the big, obvious ones. There are others, some of which may not really be considered barriers but more like impediments. One of those might have a better solution soon, and that’s the time-mandated Phase I flight test period. As we know, Experimental/Amateur-Built aircraft with certified engine-and-prop combinations (and both ends of that equation have to be true) are eligible for a 25-hour Phase I flight test. Because most homebuilts have as one part of that equation non-certified parts, the typical Phase I period is 40 hours.

Back when there were more aircraft whose entire flight envelopes were far less known, and for airplanes trying genuinely new powerplants and system configurations, there was some sense in mandating a 40-hour test period before passengers could be lofted or the airplane could leave the confines of its test area. You would be genuinely busy for the entire 40-hour process and might not even be done by then. I know a few airplanes that are technically in Phase I but are really flying testbeds. (And to some extent mine is among them.)

But Today?

It’s different in our world now. The bulk of the new Experimentals reaching flight today are tried-and-true designs, and more builders, when they do innovate, are more likely to do so “around the edges.” It’s not that no one experiments or innovates, because that happens every day, but the CG of our whole sport has drifted toward more “conventional” designs with “conventional” engines and, increasingly, systems and avionics layouts that are almost industry standard.

What does that mean for flight test? Mainly, you’re not really proving big concepts—like does the wing work and will the engine fail to immolate itself?—but determining if your combination of well-understood components is airworthy. These are very different things, and what most homebuilders today experience is more like production flight test than the “hold my rivet gun and watch this” kind of flight test from the early days.

Both EAA and the FAA are on the same page here. As this is written, revisions to the advisory circular (AC 90-89B) have been published in draft form by the FAA with an open comment period, which has since closed. If the FAA accepts changes to the AC outlined in the draft, it’ll mean that builders will have an option of a “task-based” compliance method in addition to the traditional time-based guidelines. “This task-based option provides at least the same level of safety and reliability that the existing hourly minimum 25 or 40 hour flight-test provides, but with the advantages of having operational completion criteria, a plan to record data for the creation of an AFM, and a flight-test report documenting the flight testing results.”

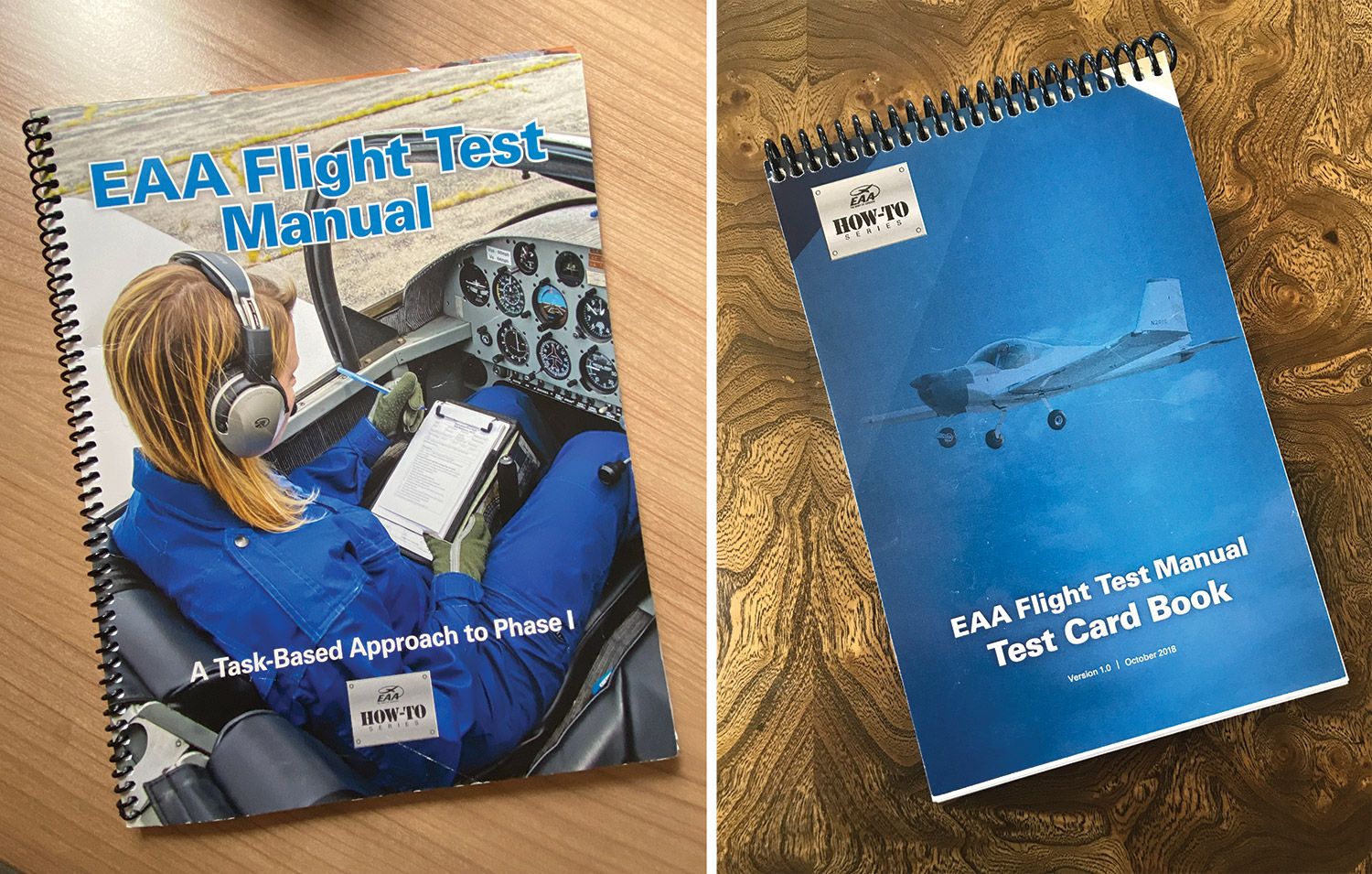

That’s a critical distinction: The FAA is saying that you could, potentially, reduce Phase I testing time (in airframe hours) by following a specified test program and completing all the steps. Of course, the EAA’s Flight Test Manual, published in 2018, will likely be an accepted means of compliance, but the AC draft revisions say that other programs, designed by the builder or by the kit manufacturer, for example, would also meet the requirements.

I’m all for this, and not completely because I think 40 hours is too long—though I do admit that I found myself repeating a few tests and working on some non-essential projects in the last few hours of my last Phase I experience. It’s because at least one alternative is a very well thought-out, thorough and completely doable program. I’ve spent a bit of time with the EAA FTM and used parts of it for certain test tasks; it’s well written and formatted in a way that encourages incremental testing and good documentation.

I’ll broaden the focus here just a bit and suggest that this move by the FAA, driven by EAA, is going to be one of those “see how they do” moments for the industry. If we take the testing seriously and use the test guides as intended, I believe we can have shorter test periods without adversely affecting safety. In fact, if all builders took the test cards seriously, I believe we’d see a benefit to safety. It’s clear that we have to prove ourselves worthy of this additional freedom before we move on to bigger and better alterations to the Experimental world that could have big, long-lasting impact.

Bottom line: Will reducing Phase I flight test from 40 hours to something shorter remove a huge obstacle to growth? No, but it helps a little and is, I think, just a baby step to a brighter future.

Another Meaning

I hadn’t fully considered another “barrier to entry” until the current CEO of a kit company called me with comments about our “Future of Homebuilding” stories in the May 2021 issue. He didn’t disagree with some of our thoughts on the near future of the sport, but offered clarity on something I hadn’t fully considered.

A significant barrier to entry for new manufacturers centers on customer expectations. Today we more or less expect most companies to have extensive quickbuild options and come off the blocks ready to offer streamlined builder assistance. If you’re talking metal, that means completely matched-hole, final-size components that need little more than assembly before driving or pulling rivets. What’s more, these customers would expect fully integrated systems that make installation of the engine, avionics and systems essentially plug-and-play.

Any new design with a hope of volume sales needs to have the very same features and support that have taken years (decades, even) to build up for the existing manufacturers. And yet these features are something new customers are likely to expect just as a company is trying to set up its manufacturing and distribution efforts. It’s like learning to ride a horse by being dropped into the saddle of American Pharoah and told, “Try not to get hurt.”

Hello, I live in Monza, Italy, and I would love to receive a copy of the manual and the test card book without spending a fortune on shipment, duty tax and so on. Any ideas?

Thanks very much,

Alex