The weather picture can be complicated

Without a doubt, Garmins introduction of the GPSMAP 396 at Oshkosh 2005 was a watershed event for datalink weather. Yes, the technology was available before on other platforms-either a high-end certified panel-mount setup or with the help of a laptop computer or PDA-but the 396 placed powerful weather data into a package many pilots could not resist. Today, datalink weather can be found on many platforms, several of which are eminently affordable. With the new Garmin aera replacing the 396 and 496, a new generation of portable devices is upon us, but don’t discount WxWorx weather ported to your Advanced Flight or Grand Rapids EFIS, or in large-format form with Garmins 696 and G3X EFIS.

The lure of in-cockpit weather was too much for me to resist, so I purchased a Garmin 396 the instant the test loaner was due to be returned. From the start, it was placed in an AirGizmos mount in my GlaStar Sportsman, and, save for a bout of system stupidity when no weather was available after New Years 2009, XM Weather has been my constant companion.

For those of you shopping for the XM Weather product, understand that there are now three levels, starting at $29.99 a month (Aviator LT), through $49.95 (Aviator) and up to $99.99 (Aviator Pro). A $75 one-time sign-up fee is charged, too.

I have used the Aviator package since day one and have, in moments of fiscal sanity, thought about dropping down to the LT. But then I look at the package breakdown and recall that the Aviator includes several info packages that I consider must haves. All systems include high-resolution Nexrad, precipitation type, city weather, TFR (temporary flight restrictions), METARs and TAFs (hourly weather and forecasts), plus county warnings. The Aviator adds a wealth of data including coverage of the above-mentioned product in Canada, winds aloft, lightning, AIRMETs and SIGMETs, satellite plus echo tops, freezing level, PIREPs (pilot reports), surface analysis and aviation weather watches. Thats a lot of information. Let me relate my experience over the last four years of flying with XM weather.

See? We have weather in California. Nexrad radar imagery is probably the top reason to have in-cockpit satellite weather. Your long-range strategizing will only benefit.

Nexrad. Probably the most impressive single piece of the puzzle. Stormscopes and radar give you close-in precip information, but nothing provides the kind of long-range picture like Nexrad. Sure, it can be slightly out of date so that in fast-moving storms and frontal systems, what you see sometimes wont agree with what the Nexrad is displaying. But the odds are very good that the depiction and reality will be close enough to keep you out of trouble. The most difficult part for me was understanding that all the green areas are very light rain, really nothing (near-convective activity aside) to avoid. You start paying attention in the yellows, and avoid red whatever you do. One year, flying to Oshkosh, I saw a huge line of storms stretching across several states, right between me and the airport. From 500 miles out, I was able to see the northern edge of the frontal line, plot a course into that edge, and as I flew along, the storm continued southeast. By the time I got there, the rain had passed.

TFRs. While we all check for TFRs before departure, I have been surprised on several occasions to see a TFR pop up while already underway. Its great to get a warning about this kind of airspace before you penetrate it, though I would prefer that the x96 units didn’t make the TFR the utterly dominant map symbol, effectively stepping on all other map detail, particularly as to-come TFRs are depicted in yellow.

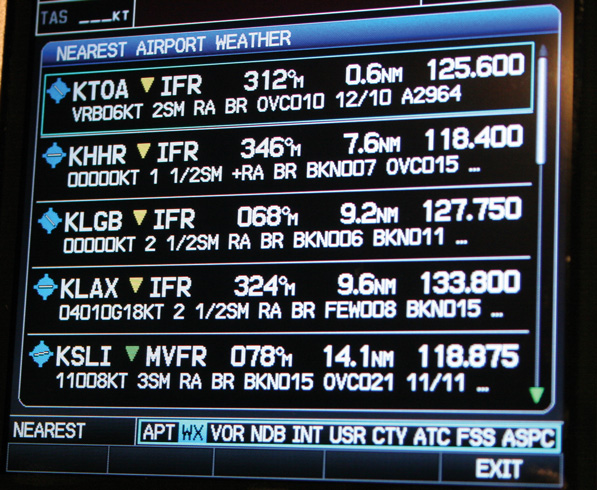

Heres a neat feature. Under the NRST (nearest) function, you can scroll over to nearest weather and get a snapshot of the METARS for surrounding stations.

METARs and TAFs. Its a delight to arrive in a busy terminal area and already know your destinations weather even if you cant leave the frequency long enough to grab the ATIS or AWOS recording. I have used METARs strategically. Returning to my old base at Chino, California, I was confronted by a wall of weather on the north side of the mountain range that separates the desert from the Southern California basin. In deciding if going over the top would leave me in VFR conditions, I needed to know what the weather was like on the other side of the range. Nexrad gave me an idea, but it wasn’t fine enough to decide. I couldn’t hear the ATIS from where I was. But when the METAR showed scattered-to-broken clouds, I knew I could top the weather at 10,000 feet and still remain VFR to the destination. Also, by watching METARs (and to some extent TAFs) en route, you can form a pretty good picture of the upcoming weather: Will it be better, the same as, or worse than forecast? Hundreds of miles out, you’ll know.

AIRMETs and SIGMETs. I use this part of the service a lot, watching how the weather develops and seeing how the weather service reacts to conditions not forecasted. During the summer months in thunderstorm territory, the SIGMETs can just about blot the screen, and are pretty broadly drawn, but they’re definitely another arrow in your quiver.

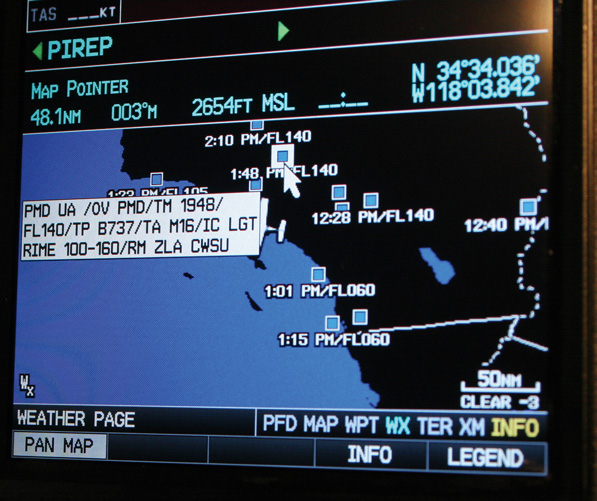

A recent addition to XM weather are pilot reports (PIREPs). Blue squares are nominal weather, yellow indicate adverse conditions (bad icing, severe turbulence, low-level windshear).

PIREPs. This is relatively new to me, recently introduced to the 496 and now showing on my Garmin G3X. I haven’t done a one-to-one comparison, but it does look like not all the PIREPs I see after landing on, say, Weathermeister, have been presented on the XM. But I consider PIREPs just one more piece of information, often validating or refuting the forecast, and helping me refine my mental picture of the weather.

Winds Aloft. Useful when trying to decide if your cruise altitude is the best, winds aloft have been, for me, hit and miss. Sometimes the forecast is right on, and sometimes its not even close. I have also seen the little wind arrows pointing 180 apart one grid cell apart when the airplane tells me the wind hasnt shifted at all. A ghost in the data, perhaps?

As far as reliability goes, I have had excellent luck, save for the widespread data outage at the start of 2009. I was on a trip then, but the weather was good; even so, I really missed my XM. The weather presentation on the G3X is definitely better than on the 496, though because I have a single-screen unit, I cant get the full-screen display like you would with the 696. I suppose $600 a year sounds like a lot for inflight, datalink weather, but it seems cheap for peace of mind.