Stephen Partridge-Hicks is English, but he races a patriotic Miss USA. For 2014 Stephen’s team extensively reshaped and lightened Miss USA’s aft fuselage, with the horizontal tail next in line for updating. At Reno he was removing the rather thick vinyl stars from the cowling as their edges were apparently catching the wind. That, and a prop change, netted Stephen first in the Silver race at 221.850 mph.

Racing is about the most fun you can have with anything internal combustion, but it costs everything you’ve got and just a little bit more. Which is why there is Formula One. When it comes to racing airplanes around pylons, there is no less expensive flight plan, other than maybe running your spare Pitts in the slower biplane heats.

The working man’s racing class since they were called Midgets right after WW-II, the Formula One class sets hard limits on expensive items such as engines and propellers, leaving plenty of room for innovation by homebuilders. An O-200 Continental engine is mandated, along with a fixed-pitch prop, 500 pounds minimum weight, and no less than 66 square feet of wing area. The emphasis is on reducing drag and increasing efficiency, traits that transition well to mainstream homebuilding.

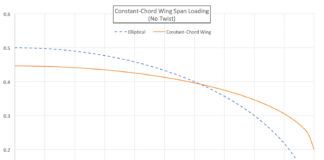

Of course, occasionally the innovation in F1 is overt. Pushers have come and gone, and there once was an F1 racer with the two mandated maingear tires set in tandem in the fuselage belly, like a two-wheel glider. In the modern era the path to speed seems paved with composites, where smooth, carefully shaped skins offer drag reductions. Near-radical wing design is another F1 hallmark; the last two decades seeing unusually high aspect ratio wings for high-G, maneuverable racers.

Start with a Cassut 111M, couple your imagination to your building skills, and you’ll have an exciting time pylon racing. Here Kent Cassels of Salt Springs, Florida, demonstrates his take on the home-brewed hot rod Cassutt; he and Margaret June finished third in the Silver at 207.349 mph.

But for every wild F1 racer in the avant-garde, there are three traditional models banking on careful build quality or the odd airframe tweak to give them an edge. Or maybe they are there just for fun with cost containment as the main motivator. Currently the F1 ranks are dominated by a carefully engineered and beautifully executed design known as Endeavor. It is followed by a gaggle of serious-minded developing racers, along with a backfield of heritage rag-and-tube designs most often run for fun, but still capable of amazing performance. And maybe most exciting for budding racers, languishing in the rear of hangars across the country are a legion of F1 racers waiting for a little love. Mainly Cassutts—a plane that’s still well supported—these planes represent one of the most approachable paths possible to rounding the pylons.

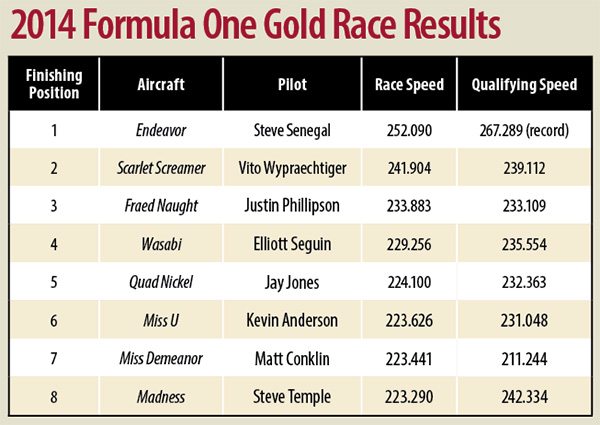

In 2014 we visited the F1 pits at Reno to recalibrate ourselves with grassroots racing developments. Our partial sampling of the racers below are arranged fastest qualifier first.

Intercontinental logistics keeps Swiss racer and Flying Bulls technician Vito Wypraechtiger in F1. Vito lives in Salzburg, Austria; his racer hangars at sponsor Ly-Con’s shop in Visalia, California. Busy with Red Bull and unable to come to the U.S. to work on his race plane, Vito could only add spraybar water to the oil cooler this year. A drive for inventive technology, small frontal area, and max horsepower keeps his vintage Cassutt 111-M consistently in the 240 mph range. Vito finished second in the 2014 Gold race.

Endeavor

“Everyone thinks we have a secret, but we don’t,” pleads Endeavor crew chief Cash Copeland. “We fly it before we come here and it’s ready to go. We un-cowl and check for leaks, things missing…This has been a very reliable airplane.” It’s a familiar story in air racing: An exceptional design is well built and paces the field without modification for years before the competition hammers out a faster unit.

Cash Copeland wheels Endeavor out of the F1/Biplane hangar at the Reno air races for another windless, early morning heat race. As smooth as if it was dipped in a vat of aerodynamic speed sauce, Endeavor is the current F1 untouchable at 267 mph.

Designed by Mike Arnold, first raced by Dave Hoover, and bought by current pilot-owner Steve Senagal in 2008, Endeavor is based in Hayward, California. The wing is foam core and carbon fiber, the fuselage Kevlar and carbon fiber. Ly-Con supplies the thoroughly detailed O-200 engine, while the legendary Al Marcucci at Savage Magneto, also in Hayward, blesses the old-school ignition with trick internal timing. The prop is a Steve Hill Twisted Composite of admittedly not overly new technology, but, as Steve puts it, “We’ve tried some pitches over the years, and this one is the best compromise between acceleration and top speed.” Race pace is a humming 4400 rpm, resulting in the current 267.289 mph qualifying record. Steve also holds the race record at 260.775 mph, set at last September’s races. That’s just a little faster than the similarly powered Cessna 150.

With its skinny-stick landing gear, razor-narrow rear fuselage, and slender wing joined at textbook right angles, Endeavor eschews any romantic notions of streamlining in favor of whatever the engineering handbook says. Under Steve’s ownership it’s also something of checkbook engineering, as he and the crew quickly point out they’re the caretakers, not the original builders of Endeavor’s speed. They’ve carefully maintained Endeavor’s winning capacity, but the breakthrough improvements were there when they bought the plane.

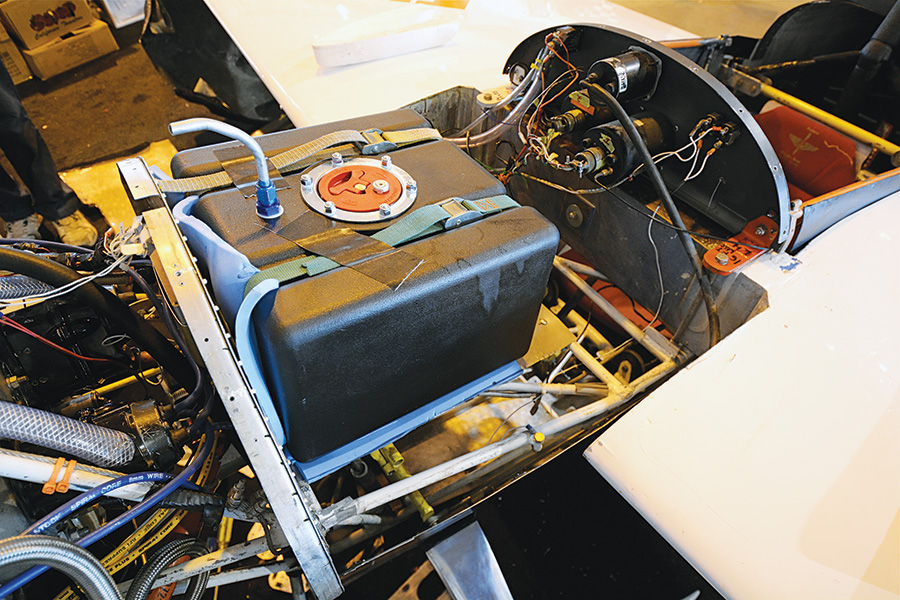

All modifications to the class-mandated O-200 Continental engine are tightly regulated to contain costs. A disproportionately large number of F1 engines come out of Ly-Con in Visalia, California, such as Madness’ shown here. Four-into-one headers into a tunnel air exit are universal on the fastest F1s.

Instead of hardware, the improvement story with Endeavor is one of the most privately held topics in aviation and sits in the pilot’s seat. Steve came to Reno after a childhood ambition for airliners took him from Watts, to flight instructing, to his own 135 charter operation, and finally, to the left seat of American Airlines iron. All that commercial flying meant next to nothing when it came to flying something light and responsive down on the deck in traffic, and Steve acknowledges the recent improvements have come from his growth as a pilot, rather than from the wax and tape tweaking they’ve given Endeavor. “It’s taken a while to get out of the mindset of staying away from the ground and other airplanes,” says Steve, before noting that, parked at the gate, the cockpit of his day-job 747 is the same height as the pylons at Reno. It’s a strong reminder that while fabrication skills grow when building airplanes, flying skills do not—and all the heavy time in the world is of little help in sport planes.

Madness

Steve Temple’s 240+ mph Madness is one of two Robbie-Grove-designed Boyd GR-7s built. The second met an early end, but Steve has been lovingly nurtured in the quest for F1 gold. This includes taking it “down to the mother material,” modifying the tail, adding fillets to the horizontal stabilizer, and smoothing the wing.

“F1 is for the guy who fiddles all the time. It’s a builder’s class. If you want a working hot rod, this is your thing,” says owner/pilot Steve Temple in Madness’ cockpit. True enough, as Steve and crew chief “Fix It” Chris Dickerson run-in four new cylinders as part of an unplanned, in-the-field top overhaul.

It’s also meant plenty of engine work, and recently, travel. Steve was invited to an F1 race in Lleida, Spain last summer. A fantastic event with large crowds out just to watch the F1s, it also proved work-intensive for Steve when Madness’ cowling partially delaminated, popping an 8-inch hole in the carbon fiber. Cowling bits stood up into the slipstream as air brakes while other shrapnel sliced the ignition system out of commission. “The explosiveness of the hole opening up felt like a rod blowing or something,” says Steve, who was no doubt appreciative that races are held right at the airport for handy unscheduled dead-stick landings.

At Reno Madness qualified second, but then the fun continued with an unexplained “washboarding” of the cylinders. Ly-Con delivered four replacements, but ultimately the troubles continued for an off-pace eighth place in the Gold feature race. Not what Steve or his team were hoping for, but part of running hard at the front of the field. For homebuilders it’s a lesson that experimenting at the limit of performance is occasionally character building.

Wasabi

Like burning magnesium chaff, Elliott Seguin is one bright wick. Not fulfilled with putting on the Mojave Experimental Fly-In, plus arranging a speed week for record setters at Mojave, and organizing non-stop flights to AirVenture—not to mention his day job at Scaled Composites—Elliott is also a blossoming F1 racer. Working a shoestring budget (no, not that Shoestring), Seguin’s one-off composite Wasabi is a mixture of advanced sport flying and F1 racing concepts with a hard-working amateur’s small budget.

Saying it’s silly to build a plane strictly for racing, deep-chested Wasabi was designed for both long-distance record setting and pylon racing by Elliott Seguin and Jennifer Whaley. It will take a fresh race engine to realize Wasabi’s full potential as it has been running on a well-used stocker.

As such, Seguin’s engine program is a wheezing lack of compression awaiting attention, hopefully this winter. The airframe, however, was designed by Elliott and his girlfriend Jennifer Whaley (also an Experimental aviation pro), and is craftily designed for record-setting, as well as F1. Sleekly molded and constantly updated, for Reno 2014, job one was a major belly-dectomy, where the fuselage was stood on end and gutted like a perch. The idea was to move the landing gear rearward 4 inches to reduce tail weight for faster acceleration during the standing starts. Typical of F1s, Wasabi has precious little rudder authority at low speeds and needs brake intervention for directional control, something to avoid like a tax audit when starting a race. Seguin reports the newly aft gear did the trick, with only minimal braking now required.

Of course, “If you’re doing the gear, you might as well do everything down there,” so a new air exit scoop was built in the belly between the gear legs, la the original Nemesis. The new gear is shorter as well for less total drag.

This trick tool caddy atop Wasabi’s fuselage is more crafty than exotic. The only custom parts are the two curved sections designed to fit Wasabi; the main portion is a bit of common plastic shelving, a task lamp and power strip outlets. A single extension cord provides power to the lamp and numerous outlets on either side of the unit.

Crawling under Wasabi shows the new cooling air/exhaust tunnel added for 2014. Every fast F1 racer uses such a tunnel with the 4-into-1 exhaust exiting through it. They also like to place a fan blowing backwards into the tunnel during post-race cool downs when not de-cowling the airplane.

Fraed Naught

Immersed in aviation for play and work—flying P-2 fire fighting tankers—owners Lowell and Judy Slatter enjoy the competitiveness of F1 racing, but ultimately, “We come here to have fun,” says Lowell.

To speed up the fun they purchased Dan Gilbert’s second, smaller and lighter F1 design three years ago, named it Fraed Naught, and have been making what detail improvements they can between all their other commitments. Some of this was simply making the airplane a little less of a handful. As Lowell explains, the racer is, “…always out of trim and has no trim tab. It’s only trimmed at 220 mph, otherwise it’s out of trim nose down. The stick forces are so light, you really can’t feel it. Every pilot who’s flown it remarks that this airplane is a little difficult to fly in the approach phase because it wants to run away.” Slippery, you could say.

Fraed Naught’s new owner, Lowell Slatter, wasn’t sure he would be able to attend Reno (in the end he did), so young gun Justin Phillipson of Chico, California flew it at Reno in 2014. In 2013 Justin piloted Outrageous, so he’s quickly building good F1 experience. Fraed Naught is flying proof a fast wing need not be thin.

Like almost every small race plane, Fraed Naught’s elevators are over-eager at speed and although the side stick is but 6 inches tall, it is “still incredibly light. I would like to change the geometry, but that takes time,” says owner Slatter. And yes, by F1 standards, this is B-1B bomber instrumentation.

Slipping to a landing would help, but Fraed Naught’s long wings and small, low-authority rudder didn’t have the leverage, so Lowell added 1 inch to the rudder’s chord and shortened the vertical tail no less than 8 inches. Now it “has way too much rudder to race, but you have to land!”

In other changes for 2014 Lowell reshaped the fuselage just aft of the cowling to clean the cowl/fuselage/wing interchange. “Chasing nano-knots,” Lowell calls it.

Unlike many in F1, A&P Lowell assembles his own engines. “I prefer to build my own engines because that way, if I win, I can brag about it,” he jokes. In 2014 that would have been some bragging as his race engine ran hot and the $2,500 back-up engine substituted because there was no time to fix the bullet.

Miss Demeanor

Matt Conklin’s story with his Catto-winged Cassutt is a classic tale of everyman’s racing. He’s run it as a family effort, and after all the fun and effort of competing in the Gold class, he’s selling it for family reasons as well.

At Reno this year Matt qualified Miss Demeanor at 230.663 mph, then stepped aside to let friend Chet Harris have his first taste of pylon racing as part of a deal where Chet got Matt some de Havilland Beaver seat time. Chet also qualified Miss Demeanor and ran it through the heat races before letting Matt have his one last go in the Gold. Matt knew it was his last race because he had already sold the plane to another party based in Mojave, California. He was “selling Miss Demeanor because it’s the responsible thing to do as a parent, not because I’m not having fun.”

Being active in aviation is the best way of preserving its future. Miles Conklin was so consumed with assembling his Zero fighter model, he paid the camera no attention. Although his dad Matt had just sold Miss Demeanor, we think Miles will end up flying the real ones someday soon.

The pair reported no large technical issues, but did stay busy with small items, replacing all the engine mount cushions during race week, along with the tailwheel. The latter is a consumable because, like many other small racers, Miss Demeanor sports a Rollerblade tailwheel. The plastic wheels eventually break, but without harm, and they’re easily replaced from the stash of Rollerblade wheels Matt keeps handy.

Predictably, Chet found pylon racing a blast and wants to return, even though he doesn’t have his own race plane (yet) and Reno’s September race dates interfere with hunting season (he’s based in Alaska). Our bet is he’ll be back!

Knotty Girl

Another grassroots racer, Phillip Goforth is a corporate pilot operating out of Midland, Texas. His Knotty Girl is a Cassutt II with an Owl wood wing, but like any good racer it’s been modified so many times we’d best think of it as a one-off at this point.

Phillip Goforth had a corner of Knotty Girl’s voluminous 16.5-gallon gas tank split at the races. He temporarily fitted this plastic 5.1-gallon tank out of the Summit Racing catalog, but ended up getting the original aluminum tank repaired in time, so it proved all for drill.

An older design, Knotty Girl is, fabric, metal and fiberglass, although some parts, such as the just-added Robby Grove horizontal stabilizer, are carbon fiber. For 2014 the emphasis was weight reduction, with Phillip trimming a smart 30 pounds from Knotty Girl. This included Grove gun-drilled landing gear (runs the brake fluid through internal passages in the spring aluminum gear), and like Wasabi, part of the new gear was to move the CG forward of the gear to get the tail up faster during the racehorse starts.

After welding, Knotty Girl’s fuel tank passed a bicycle pump induced pressure test. The sofa in the background is just one of the comforts of home teams bring to Reno’s austere F1/Biplane/Sport hangars. It gets used all race week long.

With the gear relocated, the cowling, turtledeck, canopy, and upper horizontal deck were all reworked or rebuilt for both smoothing and reduced weight. Phillip also made the turtledeck easily removable for maintenance. The belly will be reworked later; for now empty weight is a svelte 553 pounds.

Eventually Phillip wants to trade the wing for a carbon fiber version of the Snoshoo unit, so a few more pounds may be shed yet.

Phillip builds his own engines, and while these have remained close to stock, he’s building something racier with ECI cylinders, stock rods and pistons, and a Pacific Continental camshaft. They make an exact profile of the F1-spec cam that eliminates the production tolerances of the stock bumpsticks; with fiscal good fortune Phillip hopes for roller rockers and ported cylinders in the new engine.

Besides Reno racing, Phillip sport flies Knotty Girl a fair amount to airshows to promote F1 racing. Thus, he’s got a larger than normal fuel tank, and the panel boasts UAV EFIS screens, one side for engine stuff, the other for navigation. It’s a touchscreen that emulates an HSI, so Knotty Girl definitely out-panels the competition.

A constant work in progress, like many in the F1 hangar, Knotty Girl shows her rough spots. But as Phillip says, “It’s not as perfect as we’d like, but it’s here flying.”

Ease of maintenance is one reason for Knotty Girl’s sharply tapered teardrop canopy fairing. It allows the entire aft turtledeck to come off the fuselage, meaning easier inspections and repairs should anything be amiss.

Knotty Girl’s fashionable flat black fuselage is actually a vinyl wrap right over some rough fabric. The vinyl was an expedient when there wasn’t enough time to get to the painter’s prior to Reno.

Last Lap Player

Creighton King, owner of timeless F1 make Cassutt and recently featured in KITPLANES [“Cassutt 111M: The need for (affordable) speed,” September 2014], has a new bond with his race plane: stitches. True to the Cassutt’s heritage as both a sport and race plane, Creighton was ferrying the factory demonstrator to the races when, en route to Wassau, Wisconsin, his cell phone slipped to the floor. Reaching for it, Creighton inadvertently de-latched the canopy, which holed the wing, fuselage, aileron, and vertical tail on its departure. It also gashed his forehead above the left eyebrow, so along with the Cassutt’s fabric, Creighton himself took a few stitches to retain his skin.

Trailering the racer home, Creighton dug through the pile of parts acquired with his purchase of the Cassutt type to come up with a KR-2 bubble canopy that, turned backwards and laid up with a carbon fiber edge, replaced the missing Cassutt lid. Next, race pilot Dave Holmgren found the fuel boost pump (maintains fuel at the carburetor when fuel sloshes to the rear of the tank during race starts) not free-flowing as much as necessary during cruise flight, so that meant installing a new pump and bypass at Reno. The system powers off a tiny motorcycle battery, which is sufficient for the 10-minute pylon races in this otherwise non-electric aircraft.

No threat to F1 front runners with its classic Hershey bar wing and everyman’s budget, Holmgren placed the Cassutt sportster fifth in the F1 Silver race at 181.795 mph. Lesson to homebuilders: A (secure) place for everything, and everything in its place.

Short-span, long-chord wings, such as the classic Cassutt silhouette of Creighton King’s Last Lap Player were once thought the fast way.

ut as Steve Senegal’s sailplane-like Endeavor illustrates (along with every other fast F1), high aspect ratio wings rule, especially at Reno’s 5,000 foot altitude. Last Lap Player qualified at 171 mph; Endeavor went 267 mph.