Back in the June 2016 issue of KITPLANES, I wrote about some simple, but very useful, doodads. Since you can never have too many doodads, whether it’s to spiff up your airplane or make maintenance and inspection easier, I figured it’s about time to throw out a couple more.

Valve Stem Access Cover Doodad

I made a set of these plastic doodads for my Jabiru a few years ago. These are best described as “spring-loaded swing-away covers to conceal the valve-stem access hole in the wheel pants.” These doodads are as much conversation pieces as functional components (perhaps more). Granted, most people cover small holes like this with tape (which I admit is lighter and more aerodynamic), but I like the way these work, and not having to worry about pulling up paint or having the tape losing its stickiness on some far-flung ramp.

The teardrop protrusions on the sides of the wheel pants are spring-loaded swing-away covers for valve stem access. Or more simply, wheel pant doodads.

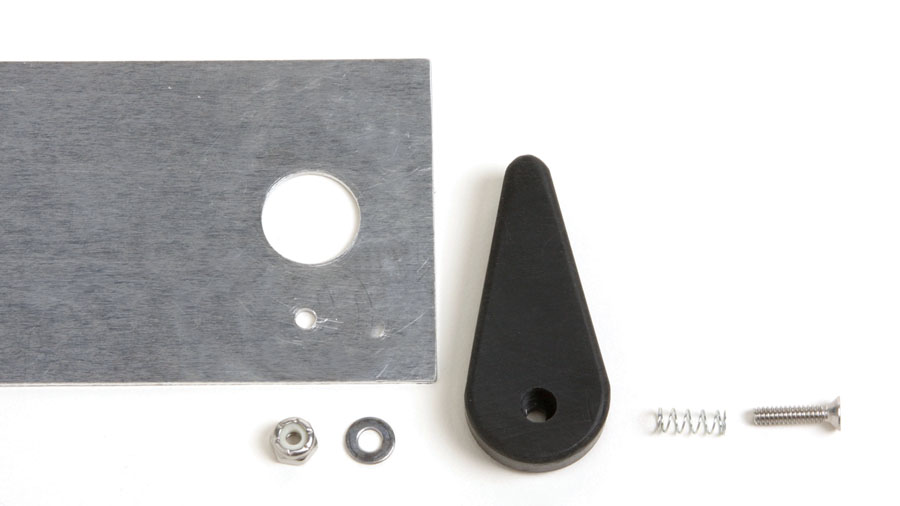

The cover pivots on a spring-loaded axle. You can download the 3D CAD file here. This file will work with any 3D printer and material.

To line up the valve stem with the hole, I painted a line on each of the tires so that the valve is lined up with the opening when the line is straight up and down. It’s as simple as flipping open the cover to check or inflate the tire. A small spring and protruding lip keep the cover in place during flight.

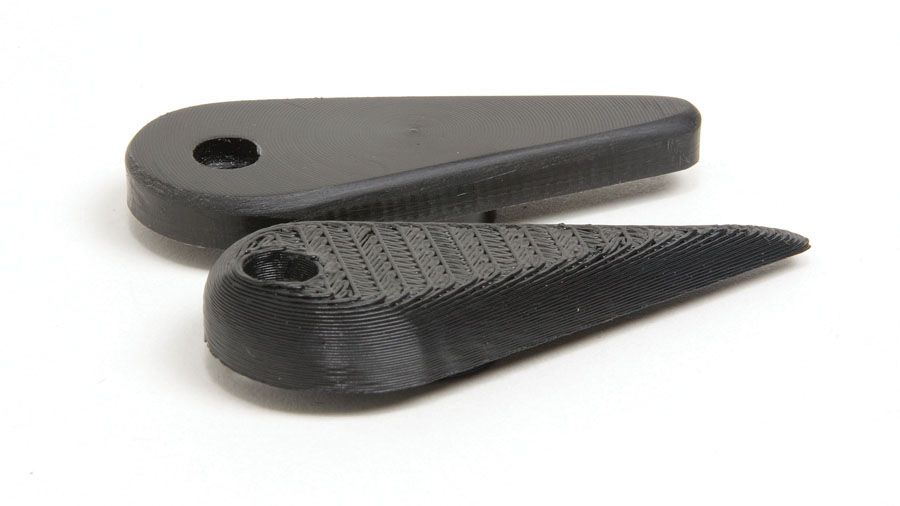

This close-up shows the difference in shape and surface finish between the machined part (top) and the 3D printed part. Note the 3D printed doodad is tapered front to back.

The covers for my Jabiru J250-SP were made on a 3D printer, but the design can be made with basic shop tools. For this column I replicated a set out of black Delrin (a type of plastic) using a Tormach CNC mill and a metal lathe. The project is a good exercise for working with plastic, which requires a careful balance of cutter speeds and feed rates to prevent melting the material.

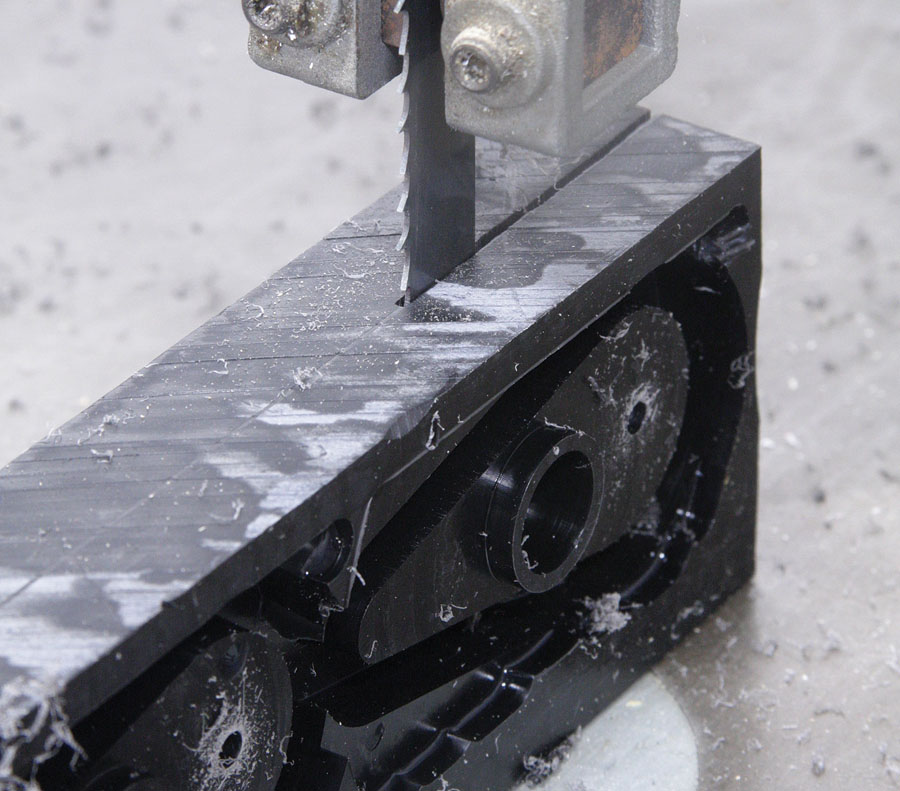

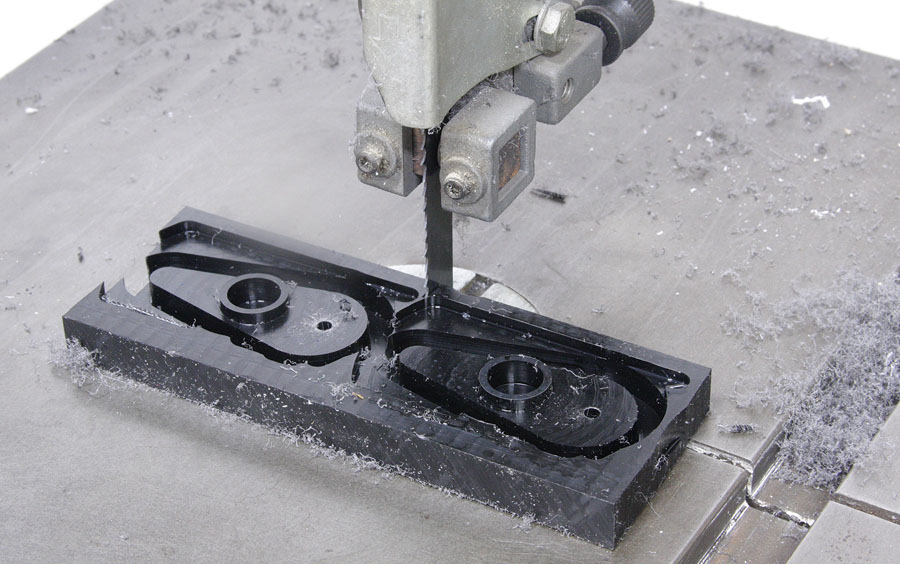

Profiling the backside lip of the doodad and milling the outside profile. Delrin machines beautifully, but is sensitive to spindle speeds and feed rates. Too much of one and too little of the other can easily melt the material. Flood coolant on the CNC machine allows for more aggressive speeds and feeds.

A plastic rod pressed into the counterbore (inset) provides a hold for the collet in order to face turn the doodad to the desired thickness.

The assembly consists of the pivot, which is a 6-32 stainless steel flathead screw, a small spring nestled in the counterbore, a flat washer, and a nyloc nut. The sheet stock provides a test mount and, if needed, a drill guide.

Adjust the pivot screw so it’s flush with the face of the doodad with the cover closed. If the screw is too tight or the counterbore too shallow, you won’t be able to lift the cover and pivot it clear of the hole.

Doorjamb Doodad

The inspiration for this doodad is illustrated by the less-than-stellar seal of the rear cargo door on my kitbuilt Jabiru J250-SP. The alignment and gap clearances are OK, it’s just when I close and latch it, the upper half isn’t snug against the forward part of the doorjamb. As you can see in the photos, there’s a good 1/4 inch protruding into the slipstream.

The doodad draws the door flush. I’m told that subsequent to my kit, Jabiru changed the hinge design to resolve this issue.

My initial solution was to fix a pivoting toggle to the top corner of the offending part of the door. This levered against the jamb to pull the door into place. But it kept coming loose and needed constant adjustment to keep the door flush.

One day the pivot screw that I epoxied into the door frame worked loose and the toggle popped off. That forced me to rethink this doodad, hopefully once and for all.

I started off by fixing the pivot. The new version was an 8-32 flathead screw, but instead of the screw itself being epoxied to the door, this time I bonded in a modified 8-32 self-threading brass insert (for wood) using a peanut-buttery mixture of flox and West System fast-curing epoxy. The modification to the insert was a lathe-turned 1/4-inch diameter flange on the end to serve as a bushing for the pivot.

A few grams of aluminum and an afternoon in the shop resulted in a simple solution to an annoying problem!

With the epoxy cured and the anchor solidly in place, I made a large-diameter aluminum retaining washer. The idea is a big washer spreads out the load across the face of the arm.

Next it was over to the lathe to make a mini jackscrew to dial in the amount of tension needed to pull the door flush. This was turned from 6061 T6 aluminum. The head was knurled (see “Gnarly Good Knurls,” November 2016) and counterbored (see “Counterbores,” May 2016), and the shank threaded using an 8-32 die.

Taking a clue from carburetor adjusting screws, a small spring was added to keep it from vibrating loose. The end of the screw is capped with a Delrin plastic “foot” to keep the screw from gouging the fiberglass doorjamb.

After a test fit confirmed the feasibility of my new doodad, I decided to add a small knob to the long end of the pivoting arm. A snap ring holds the knob in place and makes for a very low profile and simple installation (see “Feeling Groovy,” June 2018). The knob makes it easier to reach back and flip the lever down so I can open the door (if I try to open the door with the doodad engaged, it won’t!). The final step was to electro-etch the date of installation (see “Trail of Crumbs,” June 2017).

This was one of those projects that was done without any formal design or technical drawings. It was strictly a design-as-you-go affair. Doodads are fun to make. They usually don’t take very long, and it’s always rewarding to work up trick solutions to fix or improve your kit aircraft.