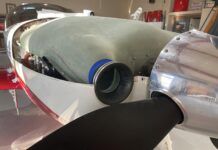

Last month we hung the engine and exhaust, so it seems a good time to fit the cowl around it all. You’ll recall that installing the engine went so smoothly that all seemed right with the world.

The first order of business, then, is to lay the upper half of the cowl on the fuselage so that the leading edge rests on the crankshaft and the trailing edge centers on the fuselage just above the firewall. That allowed me to see that my repositioning of the engine/mount put the crankshaft on-center. From there, it was a simple job to mark the high point, measure the diameter of the crankshaft, add a half-inch to that value, and then scribe a semi-circle on the upper cowl. A quick pass with a pneumatic saw, and I had a nice fit.

I want to emphasize here that if you are going to work in composites, you really need to buy the right tools. They’re not expensive, but not having them is, and this $20 pneumatic saw is one of the most valuable.

Back to the cowling: I wanted to minimize the gap between the spinner and the cowl, so the next fun step was to add the spinner. This is the sort of progress that makes me go into the house saying, “Hey, Honey, guess what I did?” It allowed me to eyeball the front end of the cowl into being symmetrical around the crankshaft. I should explain here that the requisite engine offset, if properly done, shifts the aft end of the engine, allowing the crankshaft to go through the center of the cowling.

Long Way ’Round

As is so frequently the case, getting from New York to Paris, so to speak, required going through Nova Scotia and Ireland (think of Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight). On my project, the prop bolt-holes were a mess, so cleaning them had to be done with care. A tap and a liberal amount of cutting fluid to flush out the junk was needed, but once that was done, the bolts moved smoothly.

I had heard of some problems with the spinner. A neighbor, James, with the same engine/prop combination, had found that the front and back of the spinner base were not parallel, the result being that the prop blades did not follow the same track. Once they were installed, curiosity demanded that I check it. Easy job: Just turn blade one (your choice) to horizontal, put a chair so that it just clears the blade, rotate the prop so blade two is close to the chair, and see the difference. I found none.

What I did find was that the spinner itself was not drilled on-center. It’s a snug fit against the six mounting bolt bushings, so there’s no way I could have installed it incorrectly. The wobble was noticeable, so I put a dial indicator on it and found that the hole pattern in the spinner base was 0.120 inch off center.

I contacted Sensenich about this, and a new one (personally inspected) was in the mail the same day. When it arrived, another go with the dial indicator showed it at 0.010 inch, and that seemed good enough. These spinner components are balanced, so you should resist the temptation to modify them; just take advantage of the great service Sensenich offers.

With the spinner in place, I was ready to resume my fitting of the upper cowl. Taping a spacer onto the crankshaft allowed the forward end of the cowl to sit at the right height; another spacer taped between the spinner and the cowl gave me the longitudinal position. Now it was time for the aft end.

Cheap Homemade Tools Redeemed

This is a little trickier, because there’s no guarantee that the joggle in the fuselage is not a wave as it curves around in front of the windshield. As it turns out, wave it did. But a fit was accomplished with a little tool that’s really nothing at all, but amazingly functional. Its use is based on a deep and subtle mathematical principle that a yard stick is 36 inches long no matter which end you measure from. Really! The tool is simply a scrap of aluminum with one end bent over to catch the joggle and the other bent as a handle. The length between is up to you, but about an inch seems sufficient. If your cowl requires the removal of more than a half-inch of material, you might want to rough-cut it to that range.

With the front of the cowl in position, use a couple of pieces of tape to hold the aft end of the cowl in place. Now slip the little tool under the cowl, hooking it on the joggle. Use a Sharpie to put a mark on the tool where it comes out from under the cowl. Next, remove the tool and turn it 180°, hooking it on the cowl in the same place that made a mark. Transfer that mark to the cowl.

You should repeat this sequence as many times as you like until you get a dotted line on the cowl. All that remains is to cut on the dotted line, and there you are: The trailing edge of the cowl will make a nice fit regardless of any wave in the joggle.

If you opt to simply cut the trailing edge using only two or three dots, you might be surprised to find that the straight line of the cowl makes an imperceptible wave on the joggle stand out like a pumpkin in a horse trough.

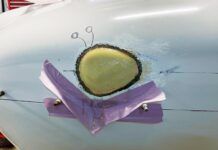

The little tool can also be used to get an equally nice fit on the lower cowl. However, in my case, the devil was in the details. Having defined and cut the opening for the crankshaft into the upper cowl, it was a task of but a moment to transfer that geometry and cut the lower half. Again, with the upper cowl resting on its spacer and taped into place on the joggle (wonderful fit!), I brought the lower half up into place and…what’s this? There’s a gap between the upper and lower cowl. These should overlap so that I can trim them to being a butt joint. This won’t do, no, this won’t do at all!

The relative position of the front end of the upper and lower cowls is restricted by their own joggle, so there’s no help there. The upper half is limited in its vertical position by dropping in to the upper joggle and the lower half of the cowling is similarly vertically restricted. There’s just no way to bring the upper half down or the lower half up.

Nothing New Here

A bit of investigation revealed that mine was not an isolated instance. It seems that during manufacture, the cowl material was laid into the mold and then, when it hardened, trimmed off using the upper edge of the mold as a guide. You guessed it: The mold was trimmed as well, so each succeeding part was just a little bit shorter than the previous part.

The most surprising aspect, though, is that I didn’t view this as an unmitigated disaster. I guess that with all that’s gone before, I have a been-there-done-that attitude. Now it’s “Aw nuts…I can fix that.” When do I get the T-shirt?

I received a suggestion to slit the lower aft end of the cowl at the 4 and 8 o’clock positions to allow the sides to come up. I was told that this would enlarge the air exit and help the engine cooling “That’s what a lot of guys do in Australia to keep the engine temps down.”

Although that might work, I just didn’t like it. There’s a large opening down there as it is, so I couldn’t see that making it larger would address this issue. The only answer, for me at least, was to extend the edges of the lower fuselage. And as it turns out, what at first seemed a job for an expert was not particularly difficult. As in so much else, preparation is everything. In this case a flat, smooth workbench large enough for the cowl was the first requirement.

The idea here is to use the surface of the bench as a mold/backing plate for the glass. Of course, we start with a sanding job of any areas that will be contacted by epoxy. A layer of slick packing tape was laid upon the bench because, while it might have been amusing, I did not eagerly anticipate permanently attaching the cowl to the bench.

Next, it was necessary to support the cowl in a position where the edge to be extended was as flat as possible and in contact with the taped bench. Various clamps and buckets sufficed, but it wasn’t pretty. Step one was to cut several lengths of glass a few inches longer than needed, lay out the needed tools, take a deep breath, and have a go.

Painting the cowl edge with epoxy was followed by mixing a separate bit of epoxy and flox and then “thumbing” it onto the sharp corners to fill any gaps. I chose to lay dry cloth in place, pour a little epoxy on it, cover it with plastic sheeting and roll out the excess.

A better technique would have been to use roven glass and work the epoxy in with a separate operation. Not having any, though, I cut my strips from larger cloth and, long and skinny as they were, they’d have disintegrated when moving them. This was done during cold weather, so it took a heat lamp and two days for it to set up, but eventually it did. Popping it off the table and repeating the operation on the other side was easy.

With the upper cowl in place and the lower cowl aft-end trimmed to fit the joggle, I was now able to mark the line of overlap on the new extension and then, using the ubiquitous pneumatic reciprocating saw, cut off the excess.

Almost There

The home stretch! Eiffel Tower in sight! Just add the hinges. The hinges on a Jabiru cowl line up nicely with the cabin doors, so, using a 12-inch drill bit, I extended the hinge pin line right through the firewall and then on through the door frame. The problem of getting through multiple walls was solved by inserting a brass tube along the pin path. It also served to closely guide the pin so that it was on track for the hinges.

One more little trick here and I’m home: Grind the tip of the hinge pin to a point, but put the point off center. The aft end of the pin is bent over 90° and about an inch long, so that when I rotate the pin I’m actually moving the point of it in a circle—and it all works! Now the hinge pins are inserted/extracted only if the doors are open.

I finished this off with 8-32 Torx screws in the lower aft end of the cowl, but I’ve seen much nicer jobs where hinges and pins are holding it directly onto the firewall. I’ll take that route a bit later perhaps, but for the moment I’m going back in the house with another, “Hey, Honey, guess what I did?”