With a flourish, RotorWay announced a new helicopter last summer to replace the venerable-and consistently popular-Exec 162F that had been the company’s mainstay for years. The new ship, called the A600 Talon, features a number of improvements to the basic 162F design-the short list includes a larger cabin, revised tailrotor power system, new instrumentation and a host of smaller changes to improve the ships utility. While the Talon looks much like the 162F, they can almost be called two different helicopters.

With a flourish, RotorWay announced a new helicopter last summer to replace the venerable-and consistently popular-Exec 162F that had been the company’s mainstay for years. The new ship, called the A600 Talon, features a number of improvements to the basic 162F design-the short list includes a larger cabin, revised tailrotor power system, new instrumentation and a host of smaller changes to improve the ships utility. While the Talon looks much like the 162F, they can almost be called two different helicopters.

The Talon is the latest iteration in a series of helicopters that goes back to 1961, when B.J. Schram put a 40-horsepower motorcycle engine into a frame and got off the ground vertically…sort of. It took six years, but in 1967 the Scorpion became the company’s first production kit. It could be built by the owner, and it actually flew. Over the years RotorWay has taken the basic design, improved it, simplified the building process and extended the life of all of the critical components. With more than 1600 kits sold, and more than 700 flying, RotorWays line is a genuine success story.

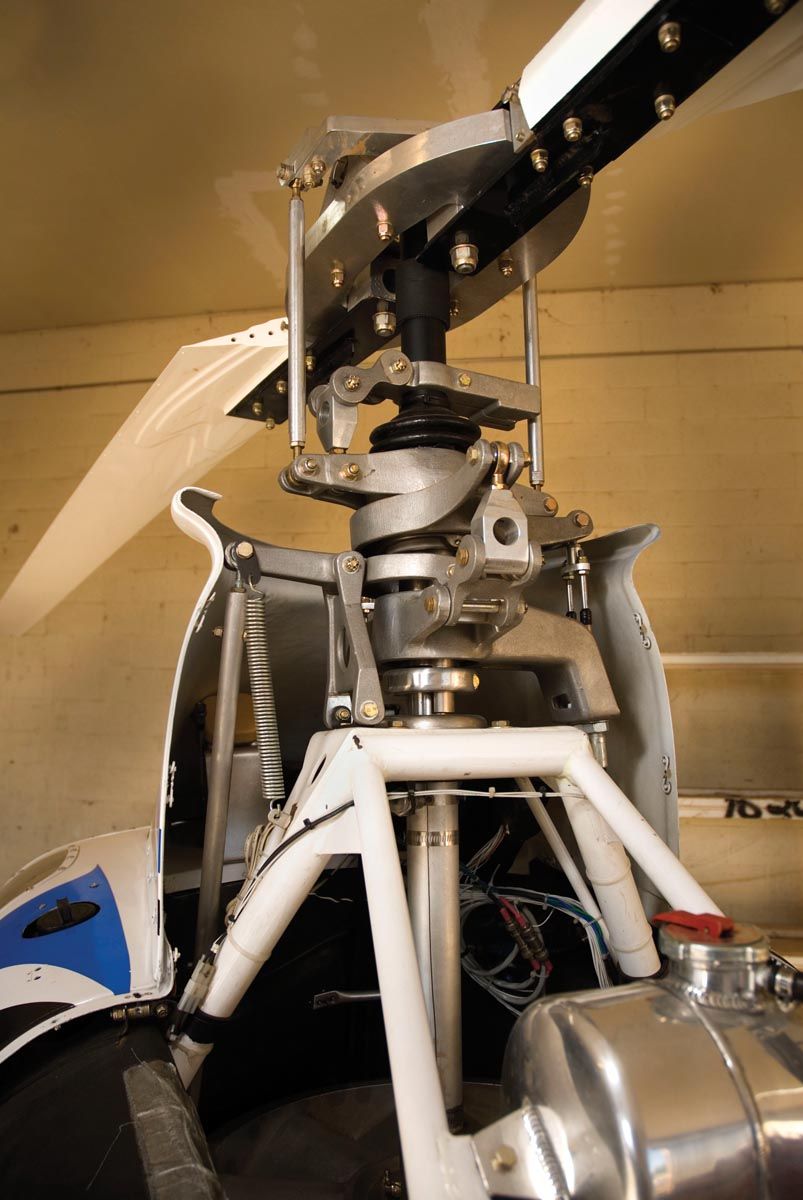

Over the last 40-plus years, RotorWay has been at the forefront of many aviation advances. The company’s engineers incorporated elastomeric bearings in the main blades, which damped vibration and made the life of the blades much longer. They gave up on the available engines and built their own, incorporating a FADEC (fully automatic digital electronic control) system in 1994, before NASA started the research for just such a system.

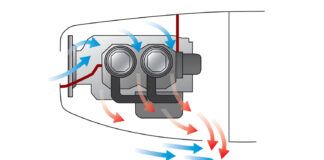

The Talons FADEC is the latest improvement and is best described as a closed loop system. The new engine-a very distant cousin of the venerable Volkswagen flat-four-has sensors that monitor all key engine parameters including the four EGTs and CHTs, coolant temperature, manifold and atmospheric pressures, oil pressure and temperature, and some others I forgot. These data are input to the computer, which in turn controls the ignition dwell and timing as well as the amount of fuel inserted into the cylinders. Unlike common aircraft fuel-injection systems, which squirt fuel into the intake ports even when the valve is closed, the RotorWays is more like a modern cars: Its electronic injectors are pulsed to meter fuel. The fuel-rail pressure remains constant, but the duration of injector opening determines fuel flow. Moreover, for extra safety, the Talon has two FADEC systems operating at all times-one is the main system, which is more “intelligent” and capable, and another “piggyback” system that is up to running the engine alone but has fewer inputs and creates a less fine load/flow map; the standby FADECs system also has fixed ignition timing.

This FADEC system is doubly important to RotorWay given that the company allows, recommends actually, that a high quality 92 octane automotive gas. Company president Grant Norwitz explained that auto fuels aren’t controlled like their aviation counterparts, so while the sign on the pump may say 92 octane, it could be much lower. The company’s research has shown that some fuels can be as much as 10 points below their advertised rating, which can cause various levels of detonation. Detonation, we all know, is bad news for any engine. With RotorWays FADEC system, the CPU will alter the timing to accommodate low-octane fuel. The pilot will note a decrease in performance, but there will be no catastrophic failure.

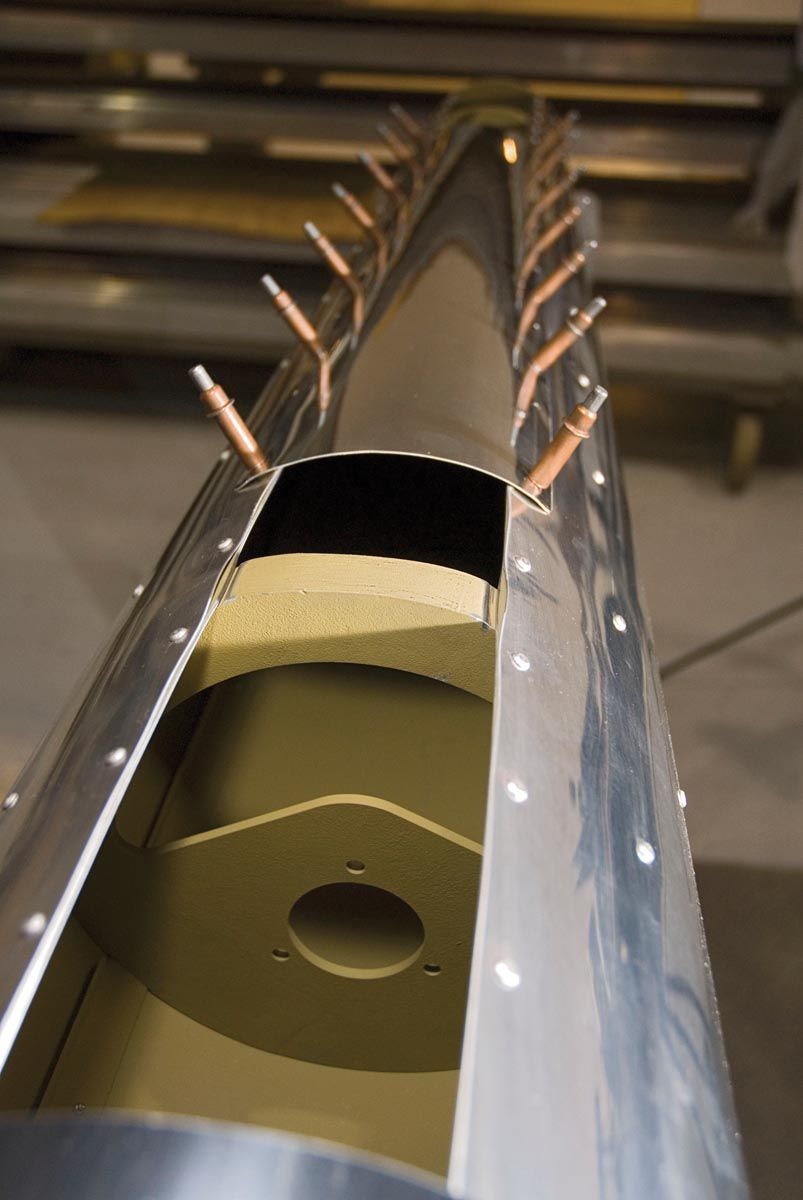

Power from the engine gets to the blades through a transmission, via a set of belts, and thence to the main-rotor shaft. In this secondary drive, the Talon uses a cog belt instead of the oil-bath-enclosed chain on previous models. While were talking about the transmission, the clutch assembly is now activated by a hydraulic ram that gets its power from the engine oil pressure. However, there’s sufficient tension for the clutch to stay engaged without any oil pressure. The main rotor can be easily disconnected for engine work, and there’s a mechanical complement in the clutch for autorotations. There is also a shaft drive for the tailrotor instead of the series of belts on previous models.

Revised On the Outside, Too

As one approaches the Talon, the most striking exterior change is apparent. The ship stands 4 inches higher, with skids that are further apart and longer. This wider and longer coupling will make for safer landings, with much less of a chance of excessive rolling. Its subtle, but the stance of the ship on the ground now makes the angle of the main-rotor mast much closer to vertical. As the instructors and their students departed RotorWays school, the Talon lifted off in a noticeably flatter attitude without the rocking we’ve seen.

Climbing in through the wide doors (no changes there), two things are striking, especially to those with experience in RotorWays. One, your butt will love the new leather-covered seats; two, your eyes will be drawn to the instrument panel. No longer is it covered with steam gauges; the Talon has entered the 21st century with a glass display manufactured by MGL Avionics of South Africa. The pilot can set the screen to many different scenarios, showing the engine and flight parameters desired as well as the GPS output. Also, perhaps a small thing, theyve installed inertial seat belts, which will contribute to comfort and safety.

The instrument display is coupled to the FADEC, so any difficulty noted by the computer will automatically show up, giving the pilot definitive data to make the land/continue decision. Later, if the pilot desires more information and/or assistance, the last 900 hours of flight data can be downloaded to a PC and transmitted to the RotorWay factory. There, the experts will diagnose and, if the computer is hooked up to the engine, adjust the CPU via the Internet-just what you need when you’re stuck in the Australian outback.

Building the Helicopter

The documentation supplied with any aircraft kit is of vital importance. RotorWay provides builders books, blueprints and DVDs (a little over 10 hours total for the series) to make the project about as easy as possible to build. We read the books, examined the prints and watched the DVDs. They are all correlated to each other, and the DVD tells you what to assemble for the segment under construction. Having a DVD, in lieu of just written documentation, is a real plus. Its one thing to say, “File the bushing and make sure its square to the fuselage” and quite another to read that and then watch the DVD, where the bushing is filed and then checked for square by installing a bolt and examining for a gap between the bolts head and the filed bushings side.

We also liked having a video to assist in the visual identification of the various components. A part may have the most distinctive name imaginable, such as “left engine cover,” but a picture of it makes for a lot more peace of mind. Given that many, if not most, of RotorWays customers are new to the building process, some of the videos may be a little overdone in their detail and simplicity for the accomplished builder. But the engineers know there are a lot of non-pilot customers who wont have much of a background in aviation, building or even mechanical aptitude. Thus little things like a demonstration of hitting a piece of wood with a hammer to drive in the landing-gear plugs seem pretty basic. Better too much information than not enough, we always say.

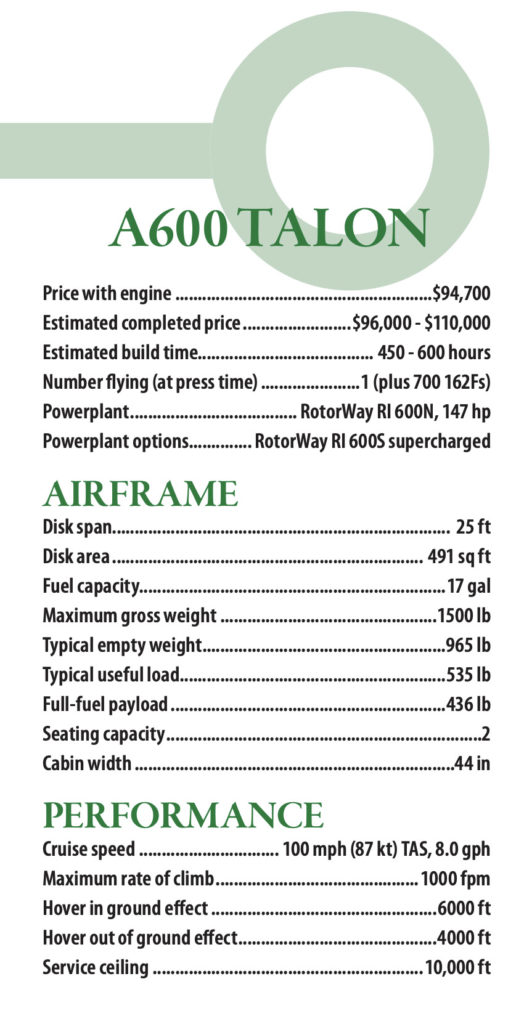

Prior to shipment, the engine is run-in on a dynamometer, the main blades are balanced, the tailboom is finished except for inspection panels, and the fuselage frame is completely welded. What the builder is doing is assembling the components. Even the fiberglass body panels, which are laid up by hand, are complete and need only be assembled to the fuselage. Nuts, bolts and sundry items are packaged in transparent shrink-wrapped packages to be opened only when needed for the specific sub-assembly being built. Aircraft-specific tools, such as Cleco pliers (and sufficient Clecoes) are supplied. They say the only things not supplied are the paint and avionics. Even with all this, the ship still qualifies under the “51% rule” for builder maintenance, and as with any helicopter, periodic maintenance is vitally important. Incidentally, the

company estimates the average build time to run between 450 and 600 hours.

Learning to Fly

I recall a fellow at my home airport trying to teach himself how to fly his RotorWay. At the time I was flying a Hughes 269 some 5 hours a day, so I was fairly proficient. The maneuverings of his ship made me hide behind a thick concrete wall. To avoid these problems, RotorWay has developed a three-phase training program, which is conducted at the company’s flight school, located at Stellar Airpark, in Chandler, Arizona. The first phase is attended when the customers helicopter is about 90% complete, and it covers hovering and ground operations as well as what to look for during the final rigging of the aircraft.

This brought up the dreadful thought of a new engine being pounded at high power settings for hours at a time-especially in Arizona. Norwitz said that wasn’t a problem, because the engine is liquid cooled and engineered for just that operating environment. He went on to say that he had been assisting in some engine research and hovered the ship for about 2 hours nonstop with an air temperature of 107 F.

The second phase of training comes after the student is proficient at hovering and introduces him/her to landings, takeoffs, cross-country and pattern work. The last phase is a final checkride for the Private Rotorcraft license. If desired, supplemental training can take the student to the Commercial rating.

The Company

RotorWay has gone through a series of owners in its history. It started with B.J. Schram, was improved under Stretch Wolter and John Netherwood, and became an employee-owned company in 1996. In 2007, the company was sold to Norwitz and a group of deep-pocket international associates. This wasn’t an impulse buy; Norwitz had run the company for a year prior to purchase, had been associated with it for two years prior to that, and he built his own RotorWay in 2003.

The intent of this group is to take the company to the next level, as its members are fond of saying. Immediately, this would mean an increase in

production from its present two ships a week and more sales overseas. A plant has been established in Cape Town, South Africa, where kits will be assembled and the helicopters sold that way. The countries that allow the sale of a pre-built Experimental aircraft include India, China, Brazil, Peru and others.

International trade is not for the faint of heart, so RotorWay has established development partners who are assisting in the process. Augusta Westland is cooperating, and has provided a great deal of assistance in development, partnering, quality control, R&D and establishing the South African subsidiary. Also on board is the Denel Company, a major manufacturer of helicopters for the South African military.

The owners have already made some large steps in expanding the company. The factory has moved about 3 miles away from its former location into an environmentally controlled, 44,000 square foot building.A nationwide dealership network is being established, which will provide parts, builder assistance and sales. The first dealership has been given to Ed

DeRossi in upstate New York. DeRossi is enthused about the possibilities. He has his own RotorWay and does builder assistance for those who live in his area.

As for media reports on the certification of the helicopter, Norwitz, and those of you who followed the travails of Cirrus and Lancairs certification process, know this is a number of years away. In the meantime, the company focuses on the Talon, which has seen a modest price increase from the 162F. The complete kit-less radios, paint, freight and flight training-costs $94,700 including the engine and FADEC. Options include a cargo container, lights and something called AICS (altitude induction compensation system, a supercharger) for $5000.

Our Flight

For comic relief, one of the pilots, John ONeill, opted to see if I had improved any in the last few years since I had been at RotorWay. We lifted off and flew to an abandoned military field just a few miles to the south. The visibility in the Talon is excellent, and with the doors off you have the feeling of flight without any support. The trick is to use the spinning rotor disk, which appears as a blur ahead, as your reference mark for turns and level flight. The controls are quick and, like most, I overcorrected, though I didn’t think a 60 bank was too bad.

ONeill did an autorotation, and the descent rate was brisk but certainly nothing that would upset a passenger. Trying to hover, I immediately remembered how old and slow I was becoming. Flying a helicopter is primarily balance and feel, so I was all over the place for the first few minutes. Once I stopped manhandling the cyclic, the ship stayed in one place, though admittedly a fairly large place.

The throttle is mechanically coupled to the collective, so raising the collective increases the throttle and vice versa. Some small input was required, but for the most part it was minimal. The tailrotor controls were sharp and definite. Because most of my time was in a Hughes 269, I consciously compared the two. The only real difference I noted was the lightness of the RotorWay, something like the difference between a sports car and a minivan.

Payload and range have always been an issue with helicopters. Their less than stellar miles-per-gallon numbers make for a regular trade-off between what you can carry and how far you can go. As for the Talons performance, it will haul a couple of 200-pounders, plus about 30 pounds of baggage and will stay in the air for almost 2 hours, providing you’re at cruise speed. How fast? Normal cruise is listed as 87 knots true, with 100 KTAS as the top speed. Thats within 10 knots of the Robinson R-22, which will burn more fuel per hour.

So it seems as though RotorWay is on a strong forward march, improving the ship, expanding production capability and looking ahead to enticing more fixed-wing pilots into the fold.

Whats in the Box?

The kit can be purchased as a unit, but many customers prefer RotorWays four-step program. This allows the builder to save space, and not have to find room for all the crates. The first shipment includes all the documentation, i.e., manuals, blueprints and templates, and the videos. Hardware-wise there’s the airframe, tailboom, landing gear, ground handling wheels, engine mount, fins, cyclic, collective, pedals, fuel tanks and heat shields. The second group has the rotor system, main shaft assembly, and most of the fuselage components. The third shipment comprises the main and tailrotor drive assemblies, the fan, oil and water cooling systems, hydraulic tensioner, fuel pumps, tailrotor, digital display, engine and flight instruments. Lastly, there are the rotor blades, engine and FADEC system. -S.W.

For more information, call 480/961-1001, or visit the web at www.rotorway.com.