A Taylor Monoplane is the perfect antidote to a boring day. With fine performance at minimal expense, brilliant handling and an undeniably fantastic breeze-in-the-hair experience, there is nothing like a Monoplane for raising a grin on the most jaded pilots face.

This lightweight aircraft is quite at home on turf strips. In fact, the lovely wind-in-your-face kind of flying it provides is almost best served this way.

This is a plansbuilt design, and you’re right: Its easier to buy a kit and bolt it together than to read and interpret plans, saw, chisel, plane, clamp and glue your way to an airplane. But if you have the skills and the patience, this neat, Volkswagen-powered design will give you sparkling handling and snappy performance at much less cost.

This is an English homebuilt design, optimized for ease of construction with a minimum number of simple metal components, which make it easier to build than most of the other similar VW-powered single-seat plansbuilts. Thanks to its minimal fuselage cross section, short, low-aspect-ratio wings and despite its antiquated RAF 45 airfoil, the Monoplane is probably the fastest of them all, plus being one of the more robust.

A Child of Taylor

First flown nearly 50 years ago after a build time of just 17 months, the prototype Monoplane was the brainchild of John Taylor, a keen draftsman/pilot, and pioneer of the post-war British homebuilt movement. His aim was for an airplane costing less than $250 with all of its main components small enough (shorter than 11 feet) to be built in his living room. Having completed them in his upstairs lounge, the wings, fuselage and tail units were all lowered from the 4.5-foot-tall second story window on ropes, sliding them down a ladder. The JAP-engine prototype didn’t perform well until a VW engine was substituted. Nearly 200 Monoplanes have since flown worldwide, including 100 or more in the U.S.

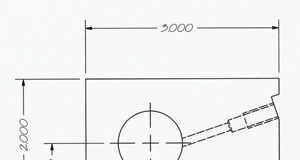

The Monoplane has conventional wood construction with semi-monocoque thin birch plywood skinning to a fuselage that is basically a simple wood box with a flat bottom, a curved top and tapering sides. The wings are similarly normal with twin built-up, laminated plank spars, ply D-section leading-edges and fabric covering. The tail feathers are all ply covered with fabric-covered control surfaces. The Monoplanes only unusual feature is that its outer wings are detachable for transportation or storage, leaving a short center section (out to just past the main landing gear) integral with the fuselage, which can easily be moved around on its wheels.

Befitting a small, light, short-rangetraveler, the Monoplanes panel is compact and fitted with low-cost avionics.

The simple telescoping maingear legs have rubber blocks in compression for suspension and few other moving parts. The drum brakes come from a motor scooter and are operated by cables linked to the rudder pedals, so that when the pedal is fully deflected, its cable tightens, activating that brake. There is no parking brake, and you cannot operate both brakes together. The tailwheel is directly steerable.

Power Up

Many types of engines have been used in Monoplanes, including small Continentals and Lycomings, plus the odd Aeronca, Franklin, Jabiru, JAP and Porsche. The bigger ones require a couple of fuselage extensions ahead of and behind the wing to maintain the correct center of gravity.

This examples Volkswagen is the simplest possible conversion of the old, air-cooled 1600cc Beetle engine with a propeller bolted on where the cars cooling fan once went, while a pair of magnetos are driven by a single duplex chain from the rear of the crankshaft. A mechanical fuel pump supplies a side-draft Solex carburetor on top of the engine, sucking fuel from a tank in the forward decking. This has a simple float and bent wire fuel gauge.

Yes, to start the engine, the propeller has to be swung by hand (though some airborne VWs nowadays have lightweight electric starters), but because this particular engine is properly set up, its easy to flip into life. Prime the fuel pump, pull out the choke, turn the engine through a half-dozen blades to suck the enriched mixture into the cylinders, switch on the magnetos and give the propeller an energetic two-handed flick, and its running. Some VW engines can be a little more difficult to start, but these can benefit from an electronic ignition booster system.

And Hop In

Getting into a Monoplane is not so much a matter of clambering up onto the wing but more a case of stepping down into the cockpit and snuggling your shoulders into the airframe like slipping on a favorite jacket. The seat is basic but comfortable with a fixed four-point harness. The Monoplanes cockpit is not huge, but its more than big enough for my 6-foot frame.

I found this little airplane easy to taxi with positive tailwheel steering and good, well-modulated brakes, which came on at full rudder deflection. Like most Monoplanes, this one has had its gear legs canted forward a little, so its heavier on the tail than many other single-seat designs. Consequently, its almost impossible to tip on its nose, though turning tightly can be a little tricky. Careful balancing of forward stick with a puff of power helps enormously.

The takeoff was over in moments, though it did take a couple of seconds for the tail to come up despite full forward elevator. I merely opened the throttle and squeezed in a sensible amount of left rudder, and we leaped into the air. The ground run was a little more than 300 feet, and we could easily have cleared 50-foot trees within 600 feet from starting in a 10-knot breeze, making this an ideal airplane for rural fields, despite its lack of flaps.

Because of its short fuselage, you need a positive (but by no means excessive) left rudder input on takeoff and during the climb. The controls might seem surprisingly light and effective to the uninitiated, but I found it a delight in flight-friendly and absolutely unthreatening. After all, this is a pure recreational vehicle, whose feathery handling and low-margin stability are, if not academically correct, appropriate for the design.

In these lightweight types of airplane, I always add 10 mph to the best-rate-of-climb speed to combat the low momentum should the engine quit. Climbing at my conservatively fast 70 mph gave me 3000 rpm at full throttle and still returned a good, healthy climb of just over 500 fpm.

You’re Inside, and Outside

This Monoplanes generous windshield protects its occupant well, though I did experience something of a breeze to the back of my head. But my body is a little longer than owner Jonathan Marten-Hales, so I sat a trifle higher. On the other hand, it gave the great advantage of superb all-round visibility. Many other Monoplanes have full canopies, which would offer improved protection as well as reduced drag for a higher cruise speed.

Leveling at 2500 feet MSL, I throttled back and searched around the cockpit to set the trim. Wait a minute, there’s no trimmer! And yet, when I come to think again, there is no out-of-trim stick force, so no trim is needed. The 3100 rpm gave me a useful 95-mph (indicated) cruise speed while reducing to a quieter 2900 rpm resulted in 92 mph. Many other Monoplanes claim a 100-mph cruise, depending on their cockpit enclosure and engine capacity.

Even at its high cruise setting, this super little airplane has light elevators and rudder, though slightly heavier ailerons-not surprising, considering their generous chord-so its harmony could be said to be less than ideal. That does not mean the ailerons ever require any real effort to move in comparison with the average Cessna or Piper, but merely that they are not as feather-light as are the other two axes.

Even better, and to my surprise, I could not generate any adverse yaw at this speed, however hard I swung the stick to the left and right. The Monoplane is nimble, responsive and sprightly. Heavy-fisted pilots would need to relax their grip and keep an eye on the airspeed when flying slowly, and dead-footed ones should learn to tap-dance on the pedals to keep in balance and be at one with this little orange darling. In other words, no sleeping at the stick.

Slowing Down

Selecting carburetor heat (always prudent with a Volkswagen engine) I completely closed the throttle, held the airplane level with the merest stick back pressure and waited while the airspeed needle subsided through 50 mph, then 40, finally sinking down through the 30s. There was no warning buffet or wing-rock, just the gentlest of nose-down pitches with the stall at a mere 33 mph. Did I imagine a sigh as the airflow caressing the wings shrugged off the task of supporting my weight? Still, just 1 mph before that amazingly low speed, we were still flying and still under full, albeit waffly, control.

Then something unusual happened. Carefully holding the airplane into its stall, it was clear we were sinking at several hundred feet per minute, still pretty much under full control, but the stick was gently snatching from side-to-side in my hand. Looking to the left and right, I could see the ailerons alternately moving up and down in concert with the control column, though the wings remained substantially level and we didn’t seem to be yawing. This was odd but not unpleasant, and merely something I had never encountered before.

The Monoplane is said to be fully aerobatic and stressed to +/-9 G. Its controls feel like those of a thoroughbred aerobatics machine, but I didn’t know whether anybody had ever performed aerobatics in this example, and I didn’t feel like being the first without a parachute. Because of this, I didn’t try any spins in this Monoplane either.

Returning to base and setting up for an approach at 70 mph (yes, double the stall speed for a safe margin), I found the Monoplane dead easy to position and even more simple to land. Because it is so lightweight and has so little momentum-and to prevent carburetor icing with the throttle closed-I did not throttle back completely, but maintained a sensible reduced power of 1500 rpm or thereabouts with carb heat selected. At this setting, we were still in trim in pitch, but now I needed a steady squeeze of right rudder to keep the slip/skid ball centered. After a slightly prolonged float caused by my conservative speed and that trickle of thrust, we touched down gently in the three-point attitude, bounced, and waddled a few times on the undulating turf, rolling to a gentle halt in perhaps 750 feet with minimal braking.

Parting Thoughts

I have had one noteworthy thought in retrospect. If you are considering buying this kind of airplane (and if you’ve dismissed the idea out of hand, think again), be sure to get checked out in an appropriate tailwheel design. Appropriate in this case does not mean a Piper Cub, Citabria or Stearman with their heavy and unresponsive controls. More suitable would be an RV-6 or an Extra 200/300L. For you’ll need to not only develop good tailwheel landing skills, but also to get in the habit of caressing the controls with just one finger and your thumb.

There is little more to say. This simple airplane is a pilots delight, easy to operate, viceless, and with handling to please even the most critical of assessors. Moreover, it is cheap to buy, easy to maintain and inexpensive to run. Most importantly, it is sheer fun to fly.

For more information, contact Terry Taylor, 79 Springwater Road, Eastwood Essex, England SS9 5BW, or visit www.taylortitch.co.uk.