Remember how proud you were as a kid to build a model airplane that looked just as good as the one on the box cover? Then there was that other kid who didn’t build the model the way it came out of the box, but was always cutting up perfectly new parts and dragging pieces of other models into his creation. Did you ever wonder what happened to that guy?

He might as well be Andy Paterson of Fallbrook, California. A serial craftsman, Paterson has made his living constructing everything from cabinets to race cars, and he has never built anything that looked “just like the box cover” including this Glasair Sportsman. It was mainly assembled by partners Chuck Hayes and Kevin Williamson, but Paterson came on board to help the harried Williamson finish the details.

When Paterson came to the project, it was nearly 80% complete. The fuselage and wings were done but were not attached. The same goes for the horizontal stabilizer, and the windows and avionics had not been installed. The parallel-valve O-360 Lycoming had been beefed to over 200 horsepower by engine house Ly-Con, using Airflow Performance fuel injection, and it had been hung on the airframe and plumbed. So Paterson had the advantage of concentrating on the finish rather then the heavy lifting of basic construction.

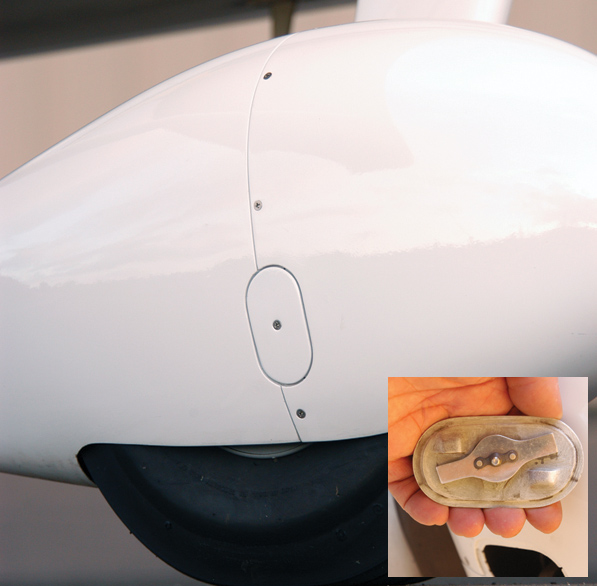

His orders were to use his imagination in finishing the Sportsman, so he had nearly free rein. The result is a superb aircraft—with a twist. On one hand the jaunty taildragger is back-country capable and wears a splatter-paint interior—a fairly common Sportsman approach. But on the other hand, it sports stylishly uptown wheelpants that are cowled tightly, faired windows, custom hinges, wingtips and fairings, and a unique baggage compartment—not to mention showboat avionics.

Leaving the wings off as long as possible, Paterson finished what little remained of the basic airframe, then went to work on the interior panels, followed by the strut and gear-leg fairings, then back to the interior for the instrument panel and glareshield. Final work took place on the cowling, which was cut and scooped long after final painting by Williamson.

As is typical, refinement of the Sportsman project continued well after its first flight. Williamson flew it some, but discovered his needs had changed and sold it to John Cook, a South African expat and Walter turbine importer now living in DeLand, Florida. At last count Cook had Paterson adding more custom touches immediately prior to flying the Sportsman to its new Florida home, with promises to bring Paterson east for annuals and continued updates. So while the Sportsman looks complete, it will continue to evolve.

The Mods

Just before the Sportsman flew east to its new home, Paterson pointed out his handiwork. Some details are purely cosmetic, but most are clever ideas that make the Sportsman a little sleeker and easier to live with. Most of these mods involve composite materials, and admittedly the resin-and-cloth world is where Paterson is most comfortable. His history with composites is extensive. He and his brother Stewart designed, built and drove their own record-setting Formula Ford 2000 race car from scratch in the 1990s—and Paterson was the man in latex gloves when Tom Aberle’s shatteringly fast Phantom racing biplane was built. No surprise then that all of Paterson’s fairings for the Sportsman are built from E-glass.

Panel and Glareshield

Thinking a glareshield should actually shield from glare, Paterson modified the Sportsman panel top by extending it back 3 inches with a more defined lip, and gave it a more pronounced curve across its upper surface for looks. He also integrated mounting pads for the compass and avionics cooling vents along the top surface. It pops in and out of the finished airplane with ease to facilitate servicing the panel.

The panel itself was also modified extensively, the contours reshaped to better fit the avionics and provide a more organic presentation. This is something of a quest of Paterson’s. With his ability to craft complex shapes in composites, he’s ready to move on from the flat-panel aesthetic in most aircraft to something more integrated and flowing. Even if it’s not immediately apparent, “There’s not a square inch on that panel I didn’t change,” Paterson said. Some of these changes are subtle, but modifications such as the recesses to clear the radios are readily visible to the practiced GlaStar owner’s eye.

The avionics were selected by the original builders, along with the backup instruments and associated switch work. Paterson executed the installation, angling the 496 Garmin and placing the analog dials relative to the electronic displays so that the mounting screws were in neat rows relative to each other. This is tedious work, but Paterson enjoys it because, “That’s what the pilot is staring at all the time.”

Door Hinges

The standard Sportsman door hinges are simple tabs that allow 180° of door opening. That makes them light and useful but also ugly, so Paterson had his own streamlined hinges whittled from billet aluminum. They double as cosmetic speed lines on the otherwise plain fuselage sides, matching the teardrop door handles.

Paterson cheated in a major way in crafting the hinges. He simply sketched what he wanted, and the pattern makers and machinists at Chuck Hayes’ joystick shop, CH Products, rapid-prototyped the hinges with stereo lithography gear. After Paterson approved the design, the hinges were executed in aluminum on CNC machinery, hence the factory-level fit and finish. Some may decry such sophisticated methods, but given that rapid-prototyping centers are currently under $15,000 for nylon “printers,” and these machines are already in the hands of advanced amateurs in the automotive field, it’s inevitable that Experimental aircraft will increasingly benefit from the technology.

The downside to Paterson’s swoopy hinges is that they add weight and give up much of the 180° opening of the stock door. As was the case with the originals, without detents the doors won’t stay open without a line or strap holding them. But the hinges are definitely showy stuff, and in the real world they have so far provided all of the opening desired.

Cowling

With its pooched cheeks, round air inlet and under-spinner engine inlet there’s not much traditional Sportsman in this cowling. Hayes was looking for something a little different, and he had a Lancair Legacy top cowling in his shop, so he grafted the Lancair upper cowl to the Sportsman’s lower. The Lancair upper turned out to be a surprisingly close fit, with the lower section requiring much more trimming and refitting to mate with its imposter other half.

Applied to the Sportsman with a veritable forest of camlocks, the cowling originally routed all air—engine cooling, oil cooling and engine inlet—through just the two round nostrils. This was definitely a clean installation, but it violated Paterson’s control-freak philosophy of segregating air management duties.

After the usual quick-fix attempts, Paterson hacked into the finished lower cowl, slitting it in two spots to form the lower portion of the inlet air scoop seen in the photos. By pulling the resulting flap of cowling material away from the cowling, filling as needed with foam blocks, shaping them and then glassing over the foam, the new scoop was made. This layup-over-foam method is a Paterson favorite because it is amazingly fast. The foam can be glued anywhere and cuts like warm butter. If he digs too deeply, he simply glues more foam over the hole and goes at it again with the rasp file and sandpaper. Once glassed and cured, the foam is scooped out and the part is finished.

About the only downside of this foam-and-glass tactic is that only a single part can be made from the lost-foam tooling. But like most of us, Paterson is in the one-off business, so that has not been an issue.

Clean Performer

One glance at the finished Sportsman, and you know it doesn’t waste speed or fuel by dragging around a collection of gaping holes and misaligned panels. That and its O-360 are guaranteed to deliver better-than-average numbers, but exact figures are not available. Controlled flight-testing was not performed prior to the Sportsman leaving Southern California, but anecdotal reports regarding its performance are favorable—comparable to the 210-hp Sportsman’s, according to the new owner.

With the Sportsman off exploring its new environs, Paterson is keeping his fabricating hand in at Aberle Custom Aircraft. His own Glasair I retractable project suffers somewhat from Cobbler’s Kids Syndrome: It’s tough to work on your own airplane after building the toys of others all day long. But as you might imagine, it is bound to be a finely detailed speedster when it finally emerges from the hangar.