Most pilots love aviation movies. Our favorite parts usually involve buzz jobs flown at insanely low altitudes. From Moggy Cattermole flying his Spitfire under the bridge in Piece of Cake to James Bond flying a BD-5 through a hangar in Octopussy to Maverick buzzing the tower in Top Gun, the high-speed low-altitude buzz job and victory roll are staples of aviation adventure.

Such behavior is often viewed as the sign of a “hot pilot,” which makes such behavior irresistible to a subset of the aviation population. Despite discouragement by many and enforcement actions by the FAA, pilots still buzz houses, pull up steeply after low runway passes, and perform aerobatics close to the ground.

And each year, such maneuvers in homebuilts kill an average of nine people. If you do pull it off, fine—but if you crash, there’s a greater than two-thirds chance it’ll be fatal to you or any passengers.

Other than not ignoring the siren call of the buzz job, what are pilots doing wrong?

Defining the Event

In my homebuilt database, I have an accident category called “Maneuvering at Low Altitude” (MLA). The category covers a fairly wide set of circumstances. Buzz jobs are included, of course, as are cases of low-level aerobatics. Also counted are runway passes that end in stalls after steep pull-ups or low-level turns, scud running, and flying into box canyons.

For this analysis, I use the term “aerobatics” in the sense of definitive aerobatic maneuvers such as loops and rolls. An abrupt pull-up after a low pass might meet the criteria of 14CFR 91.303, but my analysis doesn’t count these with the “aerobatic” cases. I also exclude cases where maneuvers were started at a legal altitude, and the pilot, for some reason, failed to recover in time.

For those unfamiliar with the term, “scud running” refers to attempting to fly under lowering clouds. It differs from continued VFR into IFR conditions in that the aircraft stays under control of the pilot; he or she is forced into the terrain while trying to maintain visual contact with the ground.

Basic Statistics

There are 194 accidents meeting the MLA criteria in my 20-year Experimental/Amateur-Built (E/A-B) accident database. That’s about 4.6% of the total.

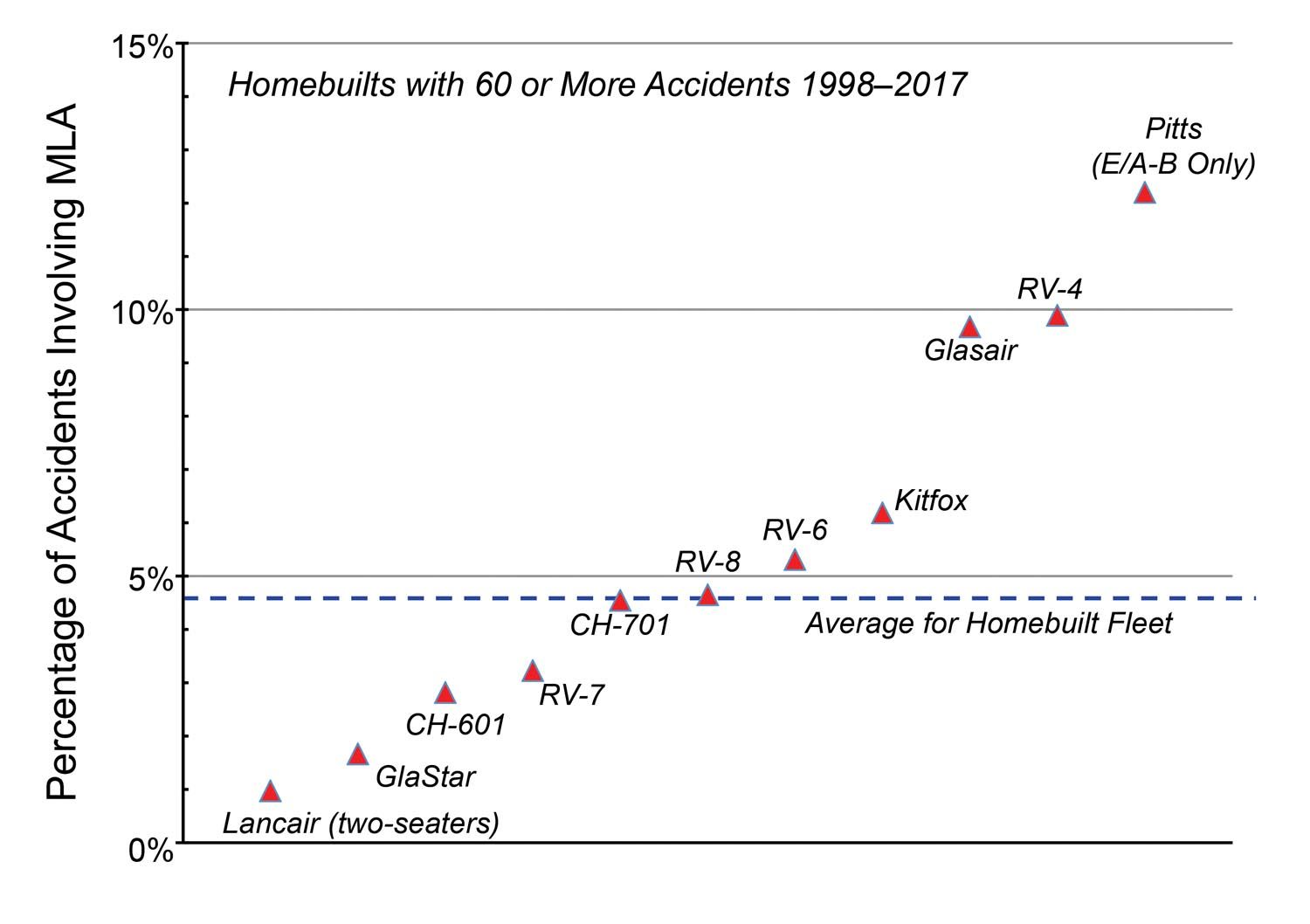

The percentages of MLA accidents for individual homebuilt types vary widely. Many types have no accidents of this kind, but for several aircraft, over 10% of their accidents were MLA. The worst I found was 16.7%…one out of six accidents of that homebuilt type’s accidents was due to unnecessary low flying.

However, this sort of comparison can be deceptive. A single buzzing accident involving a relatively rare homebuilt type can disproportionately raise its rate.

We can avoid this by looking only at the more-common homebuilt types; a larger fleet tends to even out the variation in accidents. Figure 1 shows the MLA accident rate for homebuilts with 60 or more accidents from 1998 through 2017. Above the 4.6% overall fleet average is a hodgepodge of homebuilt types: Pitts Specials, Kitfoxes, Glasairs, and a couple of RV models.

Accident Circumstances

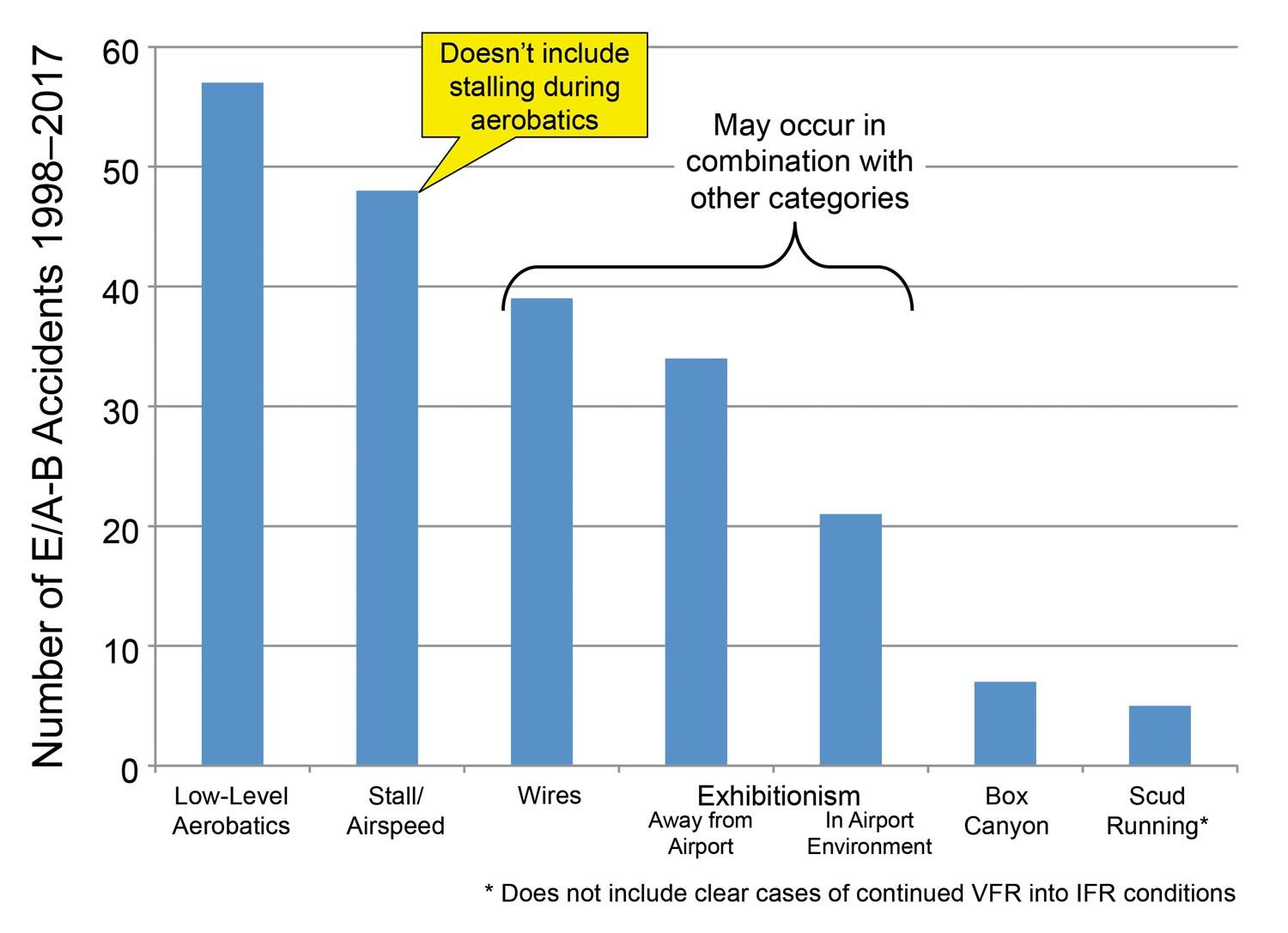

There are a number of ways to become an MLA statistic, and Figure 2 summarizes how often each occurred. Leading the list is low-altitude aerobatics, followed closely by stalling during a low pass or buzz job. Hitting wires is number three.

An accident can show in more than one category in Figure 2, and “exhibitionism” is a prime example. These are accidents where MLA activity was at least partially motivated by a need to “show off” to people on the ground. This is admittedly a judgment call on my part. In most cases, we don’t know for sure whether the pilot was grandstanding for observers. But when the accident occurs near the girlfriend’s house, or people in boats are diving into the water due to the proximity of the aircraft, one has to presume a bit of showboating was involved.

In Figure 2, exhibitionism is split into two categories, “away from airport” and “airport environment.” One of the scarier aspects? In about a quarter of the away-from-airport cases, people on the ground report the occupants of the plane waving at them prior to the accident.

MLA events around the airport tend to be less flagrant, probably due to the knowledge that illegal aerobatics are more likely to be reported. Instead, these accidents generally stem from steep pull-ups and tight turns after low passes.

Taking a Different Slant on Types

As mentioned earlier, one has to be cautious about computing an MLA accident rate when the total number of accidents of a given type is low. Instead, let’s just look at the raw number of accidents each type has suffered, rather than computing the percentage of the total.

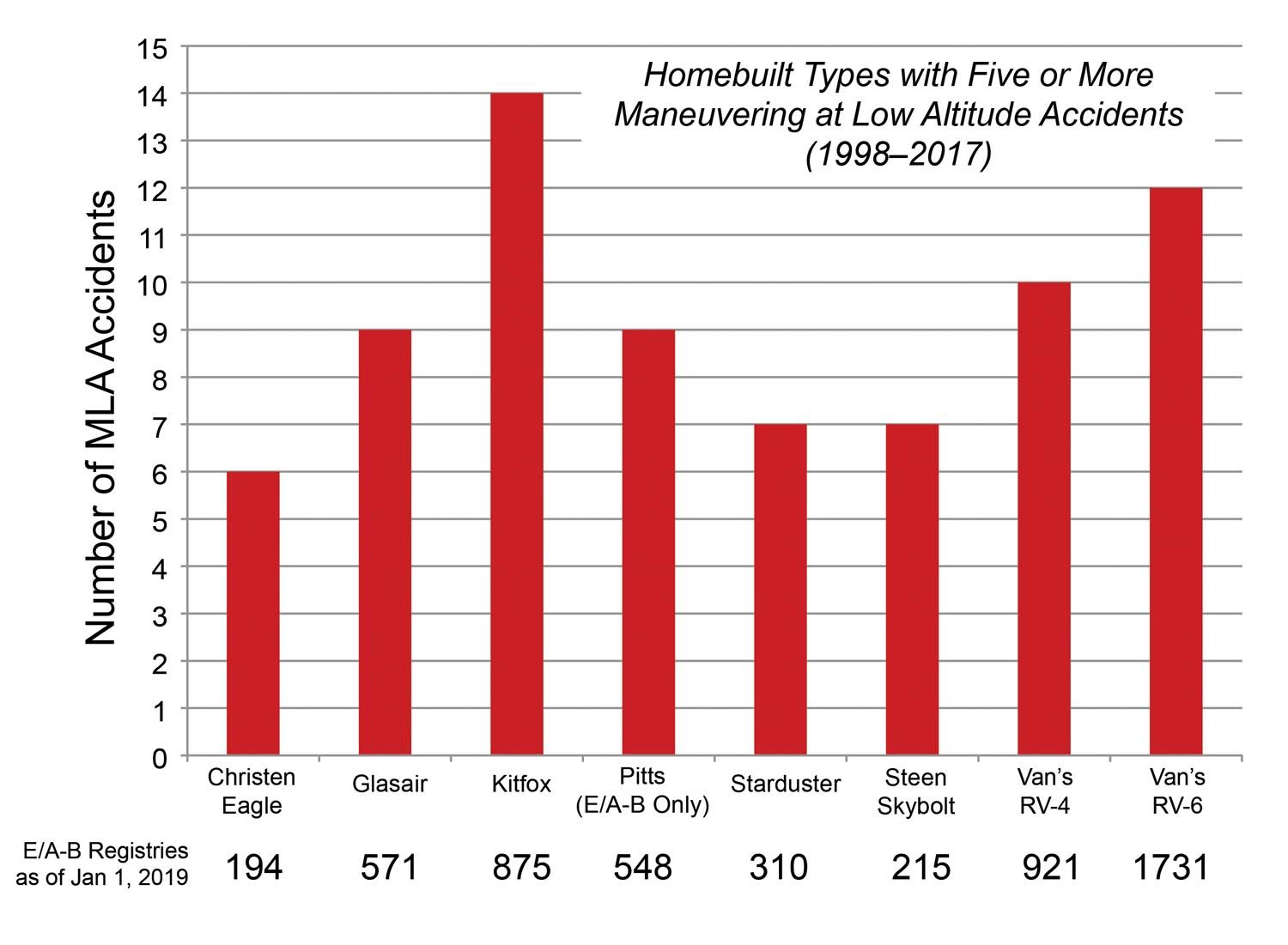

As mentioned earlier, there are 194 MLA accidents in the 20-year span of my accident database (1998 through 2017). Out of over 700 specific homebuilt types in my database, eight suffered five or more MLA accidents. These are summarized in Figure 3.

This “five plus” list contains all the “above average” aircraft in Figure 1, and adds three more: the Christen Eagle, the Stolp Starduster, and the Steen Skybolt.

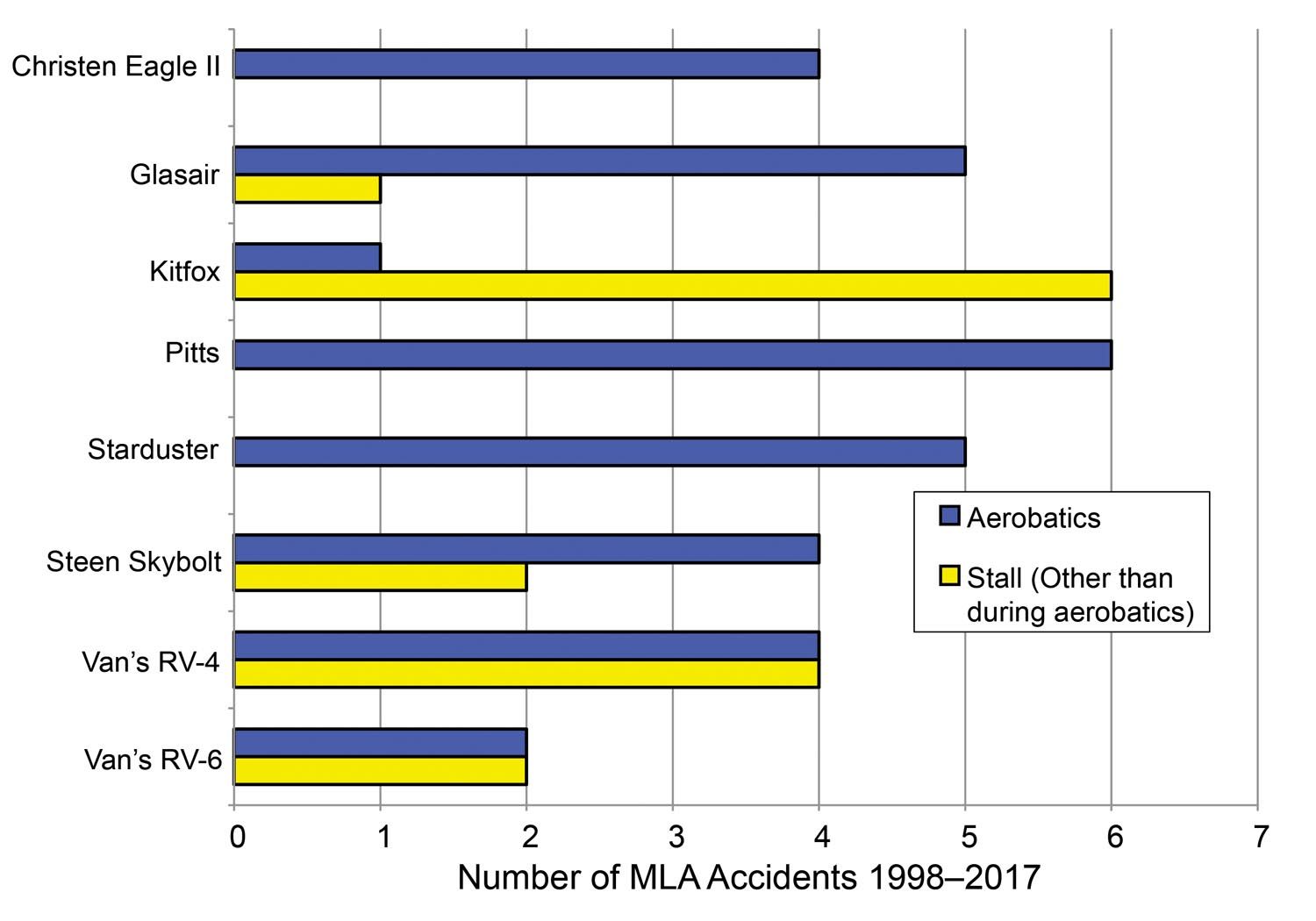

With those additions, half the airplanes in the “five plus” list are small biplanes commonly used for sport aerobatics. For all four of these types, the majority of their MLA accidents involved low-altitude aerobatics. Figure 4 shows the breakdown of aerobatic vs. stall MLA accidents for each type.

While the Glasair, too, had a (slight) majority of aerobatic accidents (five out of nine accidents), the other three planes on the list (Van’s RV-6 and -4, and the Kitfox) had less than half. Only two of the 12 RV-6 accidents and one of the 14 Kitfox cases involved low-altitude aerobatics.

The fact that the Kitfox led the MLA list was pretty surprising. Yes, there are a lot of Kitfoxes on the FAA registry, but there are twice as many RV-6s, and they still suffered fewer low-altitude accidents. Almost half the Kitfox MLA cases involved stalling; otherwise, there just seems to be a lot of flying into things.

There’s one thing we have to keep in mind: There’s nothing about any of these aircraft forcing the pilots to take chances at low altitude. Some models may appeal to those more prone to take risks, while other types may have a ragged corner of the performance envelope that will bite in some circumstances. But it isn’t the airplane’s fault it’s being flown so low.

“Hold My Beer?”

One thing airplanes don’t do is drink booze. How often is consumption of alcohol involved in low-altitude flying accidents?

In my main database, alcohol is listed as a contributing cause in only 16 out of 4041 accidents, or about 0.35%. But three-fifths of those cases (no pun intended) were MLA accidents. About 3% of all MLA accidents had alcohol involved. That’s almost 10 times higher than the overall rate!

However, keep in mind the relative rarity of these events. That “3% of MLA accidents” is still only six accidents out of 194. Not that significant over 20 years.

Wrap-Up

Pilots who engage in dangerous activities usually dismiss the safety issues. They’ve “thought things out” and are “managing the risks.”

But there are graveyards full of pilots who thought they had the risks managed. The pilots in every one of those 194 cases in my database (an average of almost 10 per year) thought they had the danger controlled. They didn’t think what they were doing was hazardous, and they felt their piloting skills were more than adequate to the challenge.

We don’t know how often a buzz job doesn’t end in tragedy or how often a pilot flies home, flushed with excitement, after successfully performing a low-level victory roll. What we do know is that if an accident does occur, about 65% of the time the pilot doesn’t survive.

Get your low-level thrills vicariously from the Fokkers in The Blue Max or the B-17 in The Thousand Plane Raid. None of these movies include a “don’t try this at home” disclaimer. But remember, even the professional stunt pilots who make these movies occasionally die during filming.

Keep it high, folks.