Learned colleague Paul Dye recently wrote about the time-limited nature of aviation hardware. That is, every bolt has its day. Eventually the cad plate wears off, surface corrosion sets in or the threads and prevailing torque functions wear noticeably. Such hardware should be removed from service, said Paul, and either binned or cast into outer darkness in the old nuts and bolts stash; the hellbox as many shops know it.

I’m flying a hellbox.

It’s what you get when combining a low-stratus bank account with a bit of romantic enthusiasm and you buy an already aged homebuilt from the dimming Paleozoic era of Experimental aircraft. You know better but do it anyway because you aren’t going to own your own airplane any other way, and you fancy your wrench-turning abilities can keep one step ahead of the parts falling off. I’m still here and flying as proof it can be done, at least this far, but as anyone who’s seen the machine in question knows, it isn’t pretty.

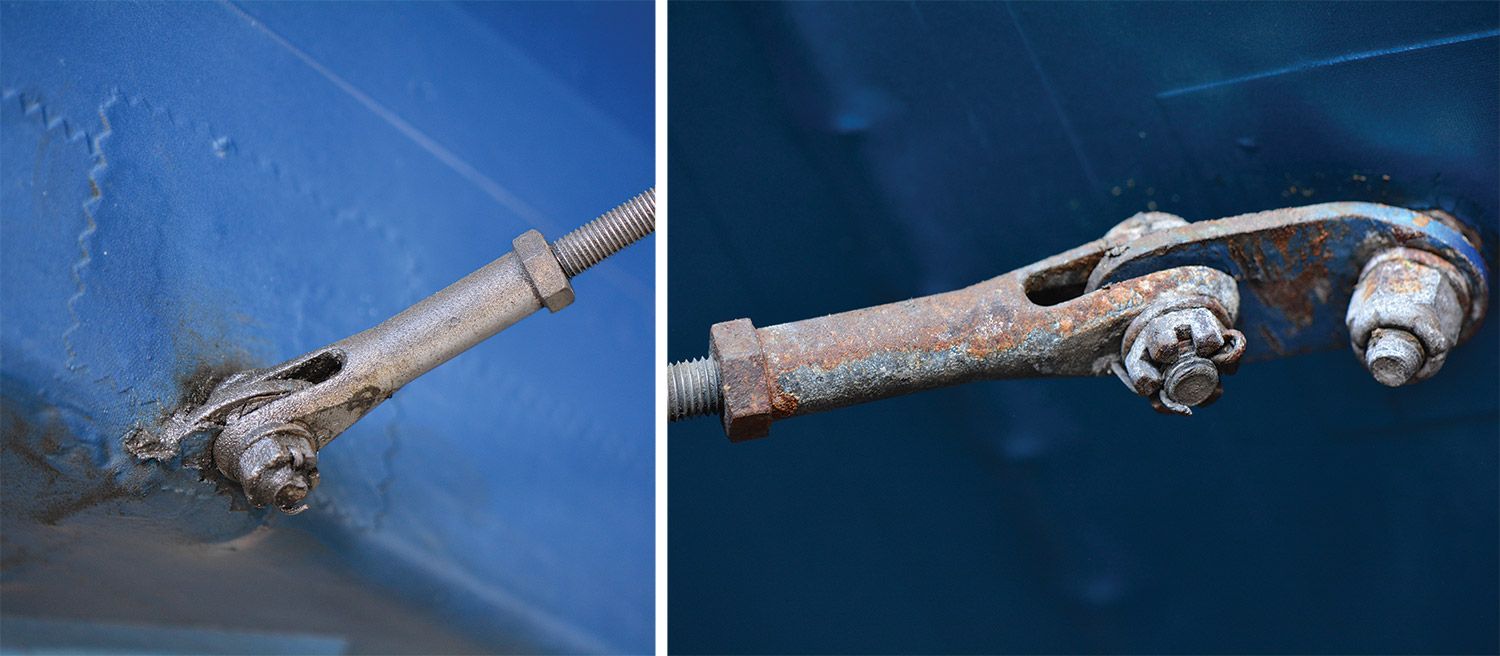

In fact, it can be downright ugly in places, but not so universally as to find relatively unmolested spots for contrast. To some extent this is because assemblages of older hardware are usually attached to equally aged machinery—the type that leaks. This is something of a blessing as oil makes an excellent preservative when applied regularly, even after being run through a combustion chamber and mixed with whatever grit gets blown on the belly. The resulting paste is self-applying, self-adhering and keeps rust and corrosion at bay on things such as tailwheel springs and forked rod ends plus their jam nuts on tail bracing wires. I speak authoritatively as the hardware attached to the ends of my streamlined tail bracing wires is that dull obscura possible only from an authentic, evenly applied oxidation patina, at least on the hardware above the engine’s oil plume line. But the metal bits well below the horizontal stab are near-new when I get down there and wipe off all the oil crud once a year. I mean, they look really good after cleaning, and they are 40 years on the job. Clearly there is a secondary benefit to oil misted from the engine compartment other than lubricating the roofs and fields of the passing countryside. I try to keep this in mind when peering into the bowels of the engine compartment in yet another fruitless oil-leak search.

But even with diligently applied neglect, it is difficult to slather the entire airplane in oil preservative. It may seem otherwise, especially when wearing a white shirt inside the hangar, but try as I might, I can’t quite get the outer wing panels covered in anything but bugs and desert grit. This has the opposite effect of ersatz radial engine preservative treatment in that dust and dirt hold moisture, and wet leads to rust or the dreaded crawling white crud in the case of aluminum. The only cure is to wash the airplane, an activity ironically banned at our county airport due to the extreme danger of oil incidentally sluicing down the stormwater drain along with however much Simple Green one used. It is permitted to leave the plane outside in the rain, which has lead to the curious situation where owners of hangared aircraft rush to the airport during one of our nauseatingly titled “rain events” here in SoCal so they can tug their pampered beast outside to sit in bad weather. An incongruous bit of maintenance, that.

Oxidation is not the only way hardware times out, of course. Turning threaded fasteners is an equally efficacious path to retirement as the threads inevitably wear, especially where tight, prevailing torque retention is used. In our hobby world this likely comes from all those condition inspections, but things such as cowling fasteners might get turned so often you wouldn’t expect them to last forever in any event. This might not be apparent to anyone operating a newer kit aircraft, but try keeping a tired engine alive while hurriedly dancing around the engine overhaul fund bonfire, and you’ll get good at taking the cowling on and off.

For an extreme example of threaded fasteners wearing to the point of unairworthiness, consider those trade school airplanes near constantly taken apart and reassembled by budding wrench jockeys. Perhaps most common in military training schools—because the military often has many obsolescent aircraft laying around for an endless supply of training school fodder—these poor birds are literally maintained to death.

And so, oil leaks or not, hardware succumbs. The trick, it seems, is to develop an eye for which hardware is more important and keep ahead of it. As the high-priority junk is replaced with new bits, the circle of priority can be expanded because the new parts have so much more of their lifespan in front of them and won’t need attention for quite awhile. A virtuous circle of improvement is thus formed, and as you invest in your safety by prioritizing and following through on your upgrade plan, the incentive grows to take better care of the airplane than the people before you may have. It’s the maintenance version of eating the elephant one bite at a time, and an important part of it on an older plane is to simply keep on eating.

In the meantime everything might not be pretty in an older Experimental, but kept well inspected and given a conscientious upgrade program such planes can be safe to fly. Keep in mind that just as it is when building a new plane, the upgrade process might not be linear. If something is unairworthy it must be attended to immediately, but after such a flurry of activity perhaps the plane can be flown a few months before the next big thing gets hands and wallet laid on it. These enjoyable flying episodes are important as they keep the pilot/owner/maintainer interested and motivated to keep improving his bird.

Ultimately, I’ve come to look at slowly (and brother, that’s the operative word) improving an older plane as my answer to the build-or-fly question so many of us work around. Flying is fabulous, but building is creative and rewarding, too. So you could start with an all-new kit and build a new plane—which is what smart people do—or you can play Lazarus with a hellbox, putting things right one step at a time. The cost is more spread out, and you can squeeze a little flying in while you’re at it. You might want to park a bit down from the pancake breakfast, though.

I think you just convinced me to buy a cool old plane built-in 82.

Oh yes, it is a bit of a Hellbox but it is so very awesome!

One of your most entertaining stories, Tom!