Way back in 2019, I gave you a fairly deep discussion of diodes and how electrons flowed from the negative source to the positive source…no matter what Ben Franklin thought his lightning bolt kite may have discovered. And I am afraid that I used that common term without much thought.

Enter a word we use rather flippantly when perusing electronic circuitry—ground. We have one person on the hook for this malapropism: G. Marconi (I use the “G” because nine times out of 10, I get Guglielmo wrong). Think about it…a metal airplane, a wire antenna ground plane, an automobile chassis, a metal radio chassis…they are all given the title “ground” without a lump of dirt in the mixture.

Words like “common,” “neutral,” “negative” and a few more are quite literally correct, but “ground” is one of those slippery little devils that we mix in without much thought. And it all started with a Marconi radio experiment back in 1902, when the first radio signals from this side of the Atlantic pond were received on the other side, from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Cornwall, England. Strangely enough, these were exactly the first and last landmarks that Charles Lindbergh flew over on his trans-Atlantic venture in 1927.

(If I may, a personal aside: I had the privilege of working on the Apollo 11 project as my first job out of college. Ryan Aircraft San Diego Space Division had the contract for doing the landing radar for that project and I had a very minor part in the process. I went to the Ryan parts warehouse, four stories tall on San Diego’s Lindbergh Field, and asked for a #2-56 screw. The foreman said they were up on the 4th floor, 31st shelf, bin 3116. I asked why they were so far away from the other hardware. The foreman said, and I quote, “We keep the surplus extra parts for Lindbergh’s Spirit airplane down here on the bottom floor, but that tiny stuff for the space program we put upstairs.” 1927 meet 1967.)

But I digress. Heinrich Hertz (1870s) declared that radio waves could only be transmitted and received from a horizontal dipole (like a VOR antenna). Marconi tried and tried again to transmit radio signals from point A to point B using a dipole without any success. He then did what all good engineers do: something different. Since a vertical dipole made no sense, Marconi rotated the horizontal dipole to be a vertical monopole with the second element(s) of the dipole spread around on the ground. After a few dozen experiments, the Marconi crew found that instead of a few dozen wires run horizontally away from the base of the antenna, a few copper rods driven deep into the surrounding ground worked every bit as well. Since they worked so well for antennas, the term “ground” was applied to the bottom element, the return element, which is the most common connection in the circuit.

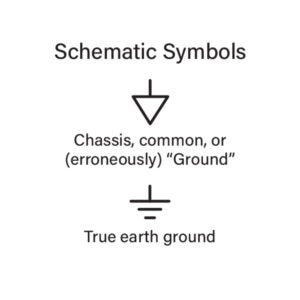

And so we can now properly explore the most elemental device in the semiconductor inventory, the diode. Note that when I use the ground schematic symbol, the thought of deep rods driven into the earth’s surface doesn’t immediately come to mind. However, there is a special symbol for when we do use rods driven into the earth for a true earth ground.

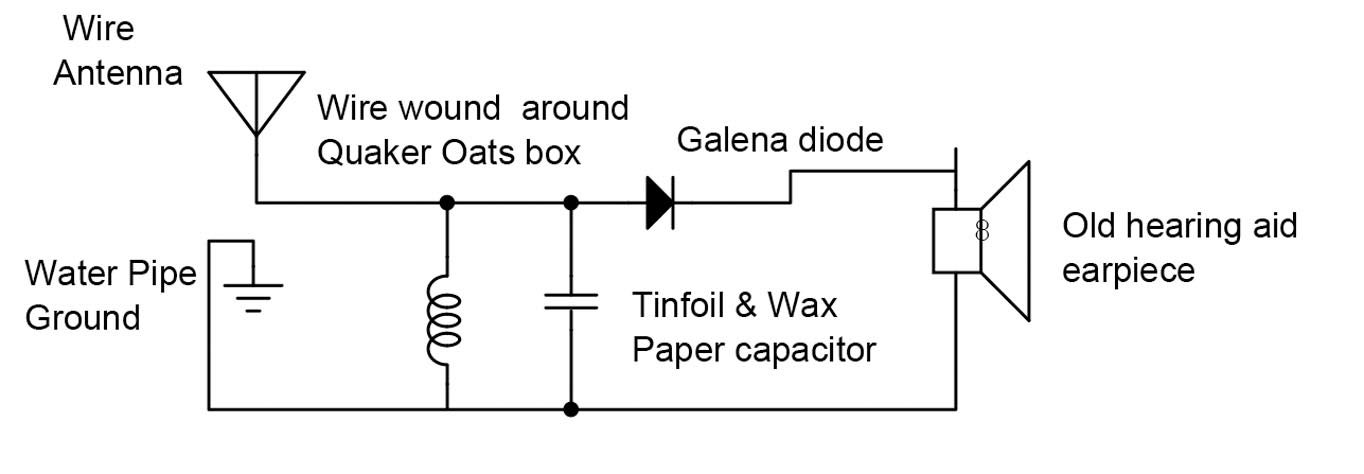

Without going into a long historical discussion of diodes, which only conduct electrons in one direction, let’s just say that Fleming in England was the one who received Marconi’s Morse code (dit-dit-dit) “S” from Nova Scotia to Cornwall and was the first receiver of signals from North America to Europe. Since Marconi’s transmitter was nothing more than a huge spark plug spitting signals in all directions, and Fleming’s receiver was a crude Boy Scout receiver using a tuned coil on a cardboard (Quaker Oats?) box and a detector using a lump of lead sulphide and a safety pin as a diode, we have the first transoceanic radio transmission from a noisy spark plug to a homemade “semiconductor” diode.

Perfect diodes conduct electricity in one direction and block it in the other direction. Since we are used to the convention of the chassis being the negative part of the circuit and the positive part of the battery being the “power source” for the rest of the circuit, let’s proceed with that fallacy. If and when it becomes necessary to use the popular lie of the (+) part of the power supply being the recipient of the electrons from the (-) part of the supply, I will remind you of the correct interpretation.

As I said, diodes conduct electricity in one direction and block it in the other direction. That also is only partially true. Diodes with the (+) supply circuit connected to the anode and the (-) supply connected to the cathode are said to be in forward conduction. There is always some small voltage drop across the diode in forward conduction. For the common inexpensive silicon diode, that forward voltage drop will be in the 0.5-volt range for currents in the microamps, 0.6 volts in the milliamps and 0.7 volts in the amps range.

There are variations on this theme. Diodes made from germanium have forward voltages from 0.15 to 0.3 volts for the ranges shown above. The problems are (a) the “reverse leakage” of germanium (i.e., how much current leaks from the diode when reverse biased) is a lot worse (an order of magnitude, which is a factor of 10:1), and (b) there is a lot more silicon (beach sand) in this world than germanium.

A couple more variations: Remember our old friend the crystal set? From sixth grade? A coil on an empty round box of Quaker Oats, a capacitor made out of wax paper and tinfoil? And a “detector” to turn the received radio signal to audio to drive an old hearing aid earpiece? That “detector” happened to be what we now call a “Schottky” diode. Yep, diodes can be used to transform AM modulation radio signals to audio using diodes. In this case, the diode was from a cathode made from a lead sulfide crystal of galena (dug from the galena mines around Galena, Missouri) and the anode from a safety-pin point made from steel.

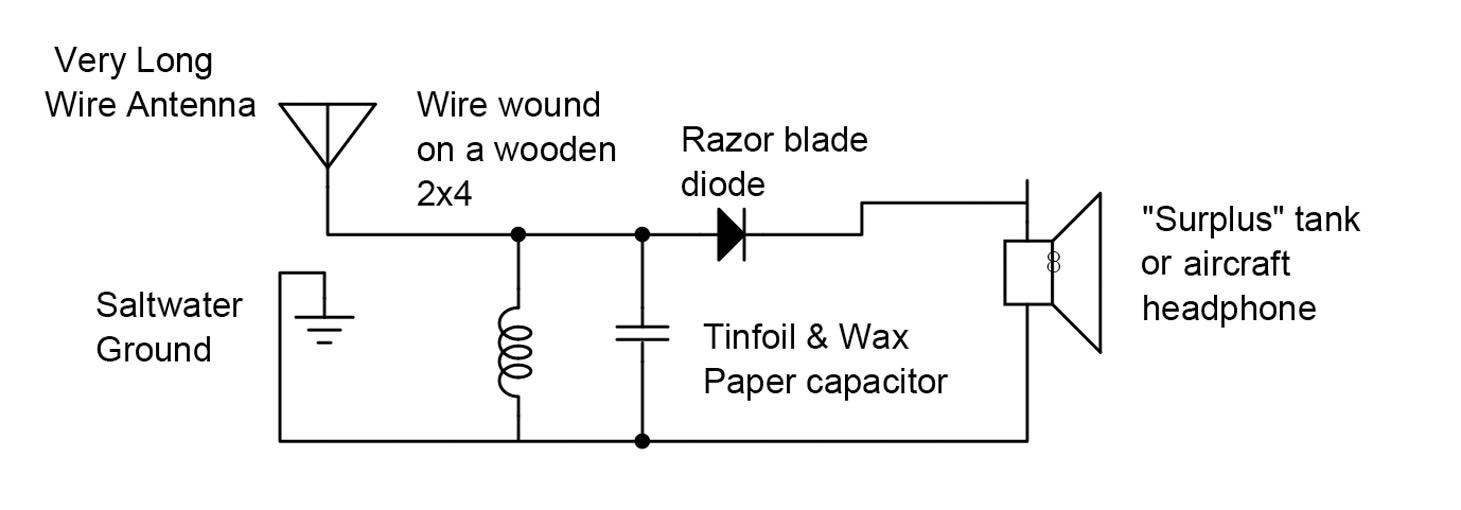

Now I’m sure this may come as a great surprise, but a “crystal set” was actually widespread during WW-II with GIs in the field. It took the name of “foxhole radio.” It seems that the coating on a Gillette razor blade was actually a silicon compound that, when oxidized (rust) due to hot weather in the South Pacific, Africa or Southern Italy became a semiconductor. There was no shortage of sharp-pointed metal objects (shell casings, safety pins, etc.), thousands of feet of wire to run as long-wire antennas (from “broken generators that can’t be fixed”) and plenty of aircraft/tank headsets that were “broken beyond repair” to let war-weary GIs listen to USA broadcast stations on the USA East and West Coasts well into the late evening. And the real ground for the long, long long-wire antenna? A few (quite a few) metal welding rods welded nose-to-tail and driven deep into the sandy island soil until they hit groundwater, which was supplied by the Pacific Ocean (a saltwater “ground plane” 3000 miles long extending from the islands to the U.S. Pacific Coast). The same goes for the Mediterranean Sea through the Atlantic Ocean to the East Coast.

I would never have believed such a tall tale, but a Marine whose name I proudly bear as “Jr.” verified that such shenanigans were in fact widespread on the Pacific Islands of Okinawa and Iwo Jima in the mid-1940s. An Army photo from Anzio, Italy, shows the same thing on the other side of the globe.

Next month: useful circuits for diodes in both forward and reverse directions.

Until then…Stay tuned…

Marconi did not transmit from Nova Scotia; Canada;

Marconi transmitted from Newfoundland Canada; from as place now called Signal Hill; east of St Johns; the capital of the province of Newfoundland; Canada.

Signal Hill and the monument to Marconi is several hundred feet above the Atlantic Ocean.

St Johns and thus Signal Hill is almost the furtherest east place in North America

St Johns has s very nice airport; CYYT, and Newfoundland is a great place to visit!

You are precisely correct, my geography error … and the stupid part is that I’ve been teaching this the RIGHT way for nearly 40 years. What most folks DON’T know and I didn’t have the space to explain is that Marconi THOUGHT he was transmitting on about 7 MHz. and what they THOUGHT the receiver was tuned to (due to the fact that nobody really understood how to design tuned circuits in those days) would have been theoretically impossible. What was really happening is that they caught first-bounce skip on the third harmonic at around 20 MHz. Thanks for reading, Jim