Are solder sleeves the best thing that has happened to wiring or are they horrible things that shouldn’t be on a lawn mower, never mind an airplane? Opinions abound on the subject and my own experience has been mixed, so some testing and evaluation was in order, or in the spirit of Joe Friday: “Just the facts, ma’am.”

Are solder sleeves the best thing that has happened to wiring or are they horrible things that shouldn’t be on a lawn mower, never mind an airplane? Opinions abound on the subject and my own experience has been mixed, so some testing and evaluation was in order, or in the spirit of Joe Friday: “Just the facts, ma’am.”

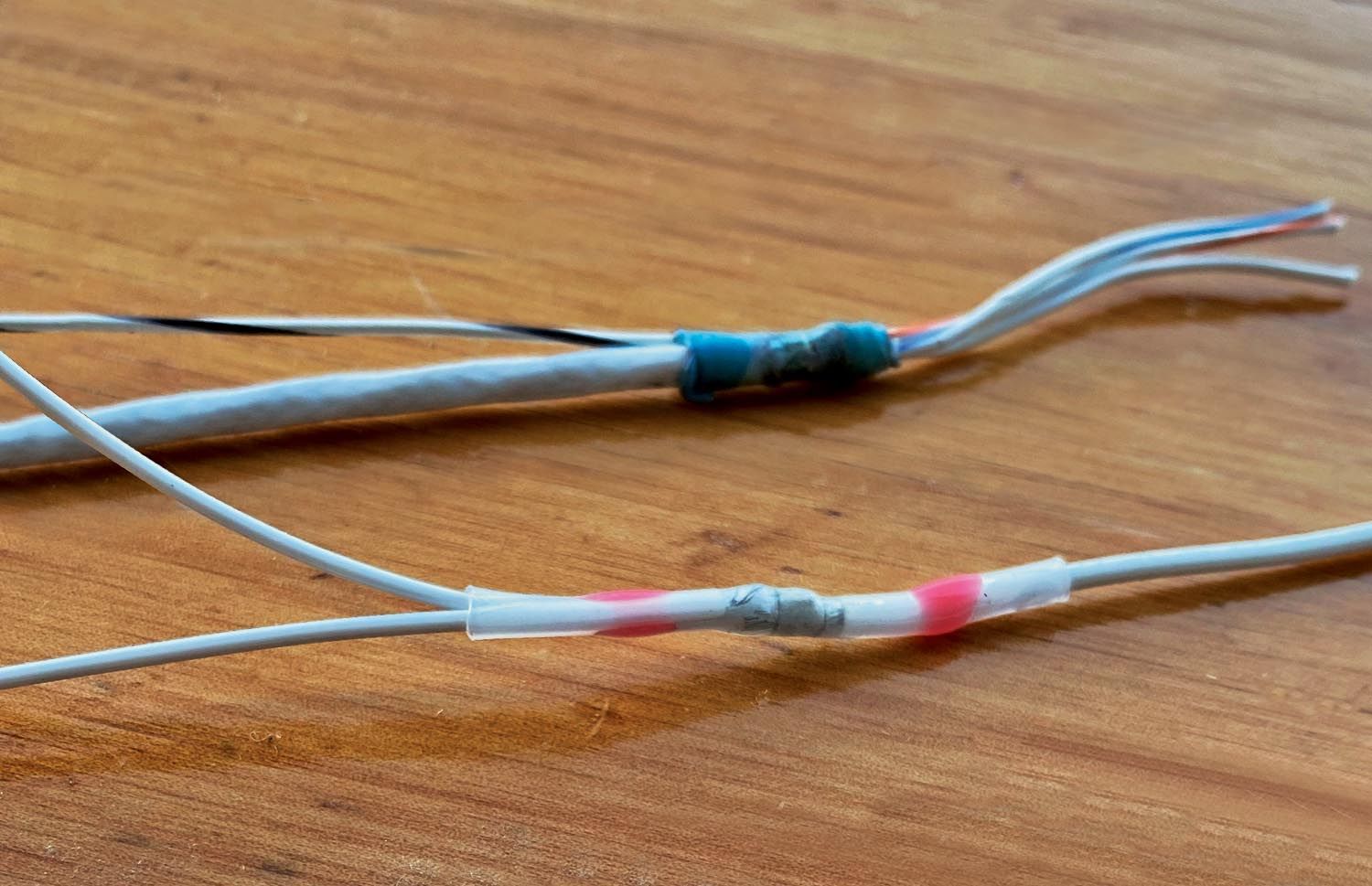

Solder sleeves are special tubes of clear heat shrink, with a band of solder in the middle and hot glue at each end. They can be used to join wires together (splicing), including attaching pigtails for ground wires to the outer braid of shielded wire without damaging the underlying insulation, using only a heat gun—no soldering required.

Traditionally, wires have been connected using solder, which is then protected with an insulating barrier of electrical tape (old school) or heat shrink (middle school). If you have done much wiring, you are probably already familiar with heat shrink; it comes in lengths of up to several feet and is cut to cover the exposed solder joint. When heat is applied, it shrinks around the joint, providing a slip-proof covering that provides abrasion resistance and electrical insulation. The hardest part about using them is remembering to slip the sleeve over one of the exposed wire ends before soldering them together (I started counting, but ran out of fingers and toes).

Heat shrink also provides benefit in the form of some strain relief of the soldered connection. The soldered portion of the wire is very inflexible, compared to the wire where it enters the solder. This provides a potential stress concentration and can lead to breakage of a wire at this point, especially if the wire is subject to vibration and/or flexing. The heat shrink helps to support the wires on each side of the joint, distributing the stress over a longer distance. Keeping the wires in properly supported bundles also helps to prevent this from becoming an issue.

Solder sleeves perform much like heat shrink and provide many of the same benefits. When shrunk, they provide an insulating barrier that provides some stress relief. This happens automatically as the sleeve is being shrunk; the same heat that melts the solder and glue also shrinks the sleeve, so they are a kind of one-stop service.

The glue bands in the solder sleeve act like hot glue, gripping the insulated part of the wire and providing some extra strength in holding two wires together. They also help seal the soldered area so that air, water and other contaminants cannot enter. In practice, the heat shrink part of the sleeve requires a relatively smaller amount of heat. The glue bands require a bit more and the solder requires still more before it flows out around the wires. Insufficient heat might cause the sleeve to shrink and maybe the glue bands to melt, but the solder will be left as a clearly delineated band, with little or no flow-out around the wires. On the other hand, too much heat will melt the heat shrink, eliminating its insulating properties. It can also cause charring of the sleeve, which is unsightly if not mechanically damaging—and everyone knows how important a pretty wire connection is!

Solder sleeves come in two flavors: the regular sleeve and the kind with a short pigtail inserted between the solder band and the tubing. The pigtail versions are typically used for shield grounds, with the other end of the pigtail connected to a ring terminal, which is screwed onto a backshell or other convenient grounding point. It is easy to start with a regular solder sleeve and make your own pigtails; just make sure the stripped wire end of the pigtail stays under the solder band as it is being melted.

One of the big advantages of solder sleeves is that they can be used inside the airplane with little risk of damaging adjacent components. With regular solder, there is a risk of dripping hot liquid metal onto carpets, upholstery or adjacent wires and avionics. If you have ever tried to solder something while upside down under the panel, you know that one of those adjacent components is your chest. Solder sleeves eliminate the risk of solder splattering where it could hurt. Applying solder also involves waving a soldering gun around. Wiggling out from under the panel with a hot soldering iron in hand is a pretty good way to burn holes where they aren’t wanted.

With all the advantages of solder sleeves, the question remains: Are they any good? We’ve done some testing to help you make a more informed decision.

The Testing Ingredients

We tested three brands of solder sleeve and five types of heat guns, as follows:

Solder Sleeves

Raychem: These are available from aviation and online sources and are considered to be among the best of the solder-sleeve alternatives. They are also the most expensive, with sleeves suitable for 22-gauge wire selling for around $1.00 each and prices going up from there for larger sizes. They have a red dye around the outside of the solder sleeve. When the red color disappears, the solder is melted.

Kuject: Ordered as a representative inexpensive kit ($16 for 120 pieces).

Haisstronica: These were ordered online, but based on the marketing information provided, looked like they might be of a higher quality. However, the price for the kit ($18) wasn’t much higher than the Kuject brand, and the per-unit price ($0.10) was actually a bit lower.

Heat Guns

300-Watt Cylinder Style: A no-name brand cylindrical style heat gun that has been in the shop for years and used on heat-shrink sleeving. Compact and easy to use with a fairly tight, directed air flow. Price: Unknown, but similar guns can be found online for about $15.

SeekOne 350-Watt Cylinder Style: A slightly higher power cylindrical style heat gun with a reflector shield. Available online for $18.

1200-Watt Heat Gun: A no-name brand heat gun, also a couple of decades old, that has been used for traditional paint and wallpaper stripping tasks. Puts out a lot of heat with a fairly wide airflow. Price: Unknown, but similar guns can be found online for about $20.

Iroda Butane Heat Gun: Has a reflector shield. This is a compact unit that does not require any batteries or source of power, but does consume butane. It has a unique feature that incorporates either a disposable BIC-style lighter or a refillable butane lighter, which is included with the heat gun. In operation there is no open flame. Uses a piezo electric ignition. Puts out a lot of heat (up to 1200° F) in a concentrated area. Available online for $35.

Wagner Furno 750 Heat Gun: This variable-temperature 1500-watt heat gun provides a digital readout of selectable temperatures and fan speeds. Includes a reflector shield. Larger and bulkier than some of the other options, but provides precise temperature control and can be stood up on a workbench with the hot end facing up. Purchased from Home Depot for $74.

The Tests

There are two primary questions when it comes to solder sleeves: (a) Does it provide an acceptable electrical connection and (b) Does it provide sufficient strength?

Electrical Connection Test

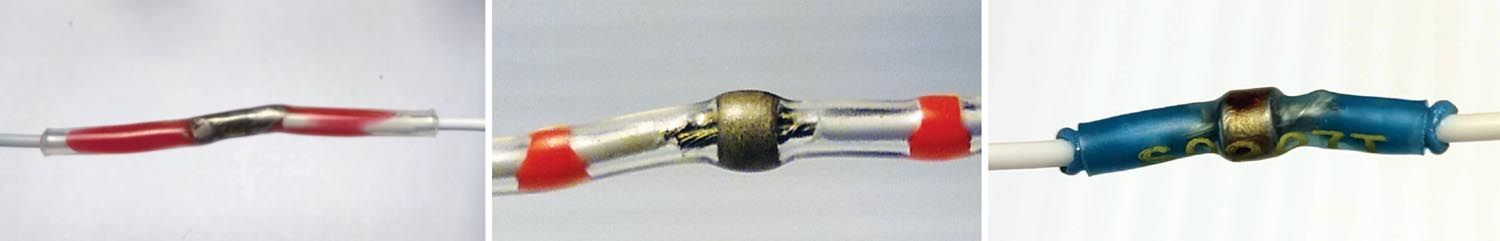

We made the assumption that if the solder has good flow-out within the sleeve, encasing the exposed portion of the wires, then the electrical connection should be good, so this part of the test was primarily a visual inspection, with the following criteria:

- Heat shrink is evenly tight across the wire.

- Glue has clearly melted and flowed out along the insulated part of the wire.

- Solder has melted and flowed out, encapsulating the exposed part of the wire in a shiny silver sheath, leaving little of the original band.

- There is no melting or charring of the sleeve or wire.

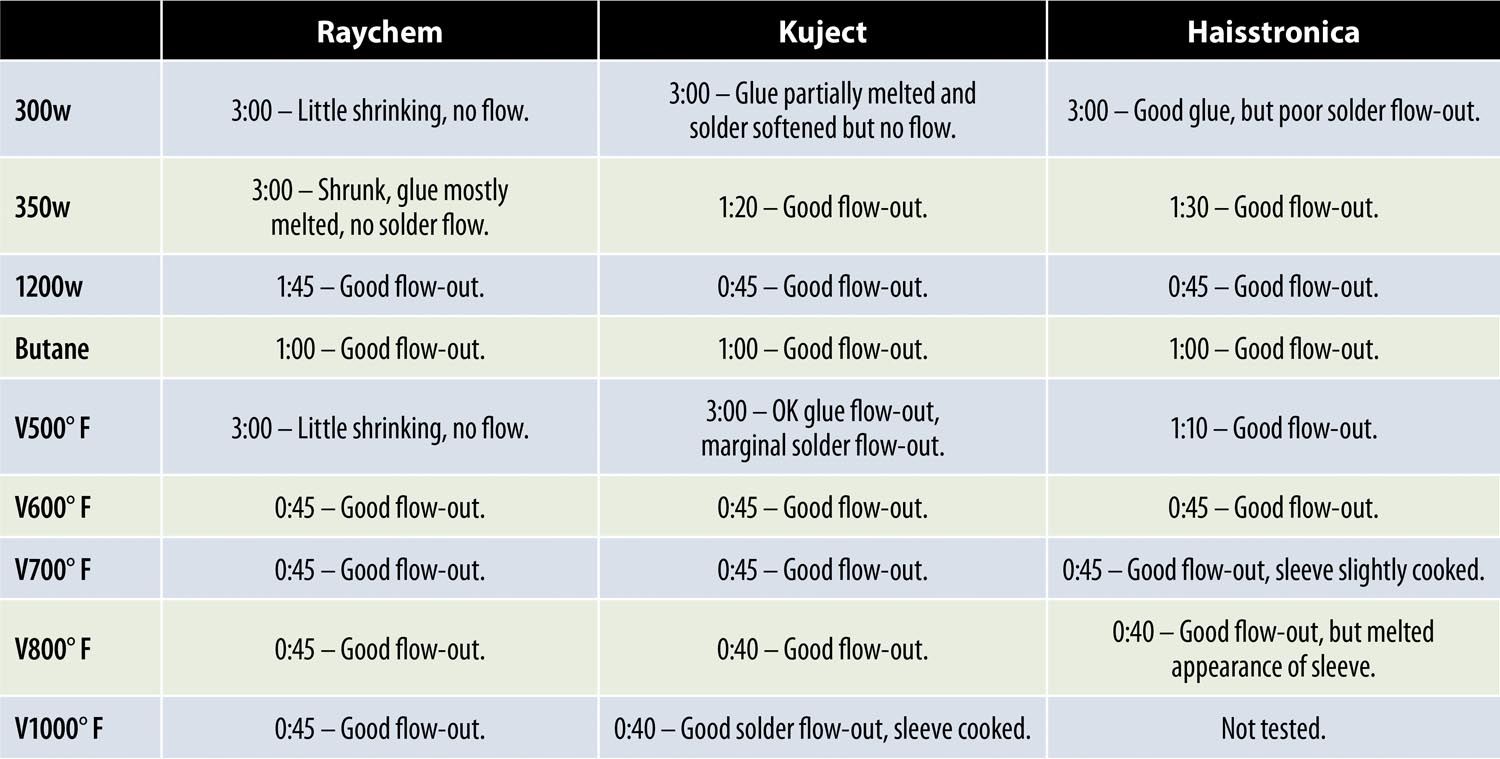

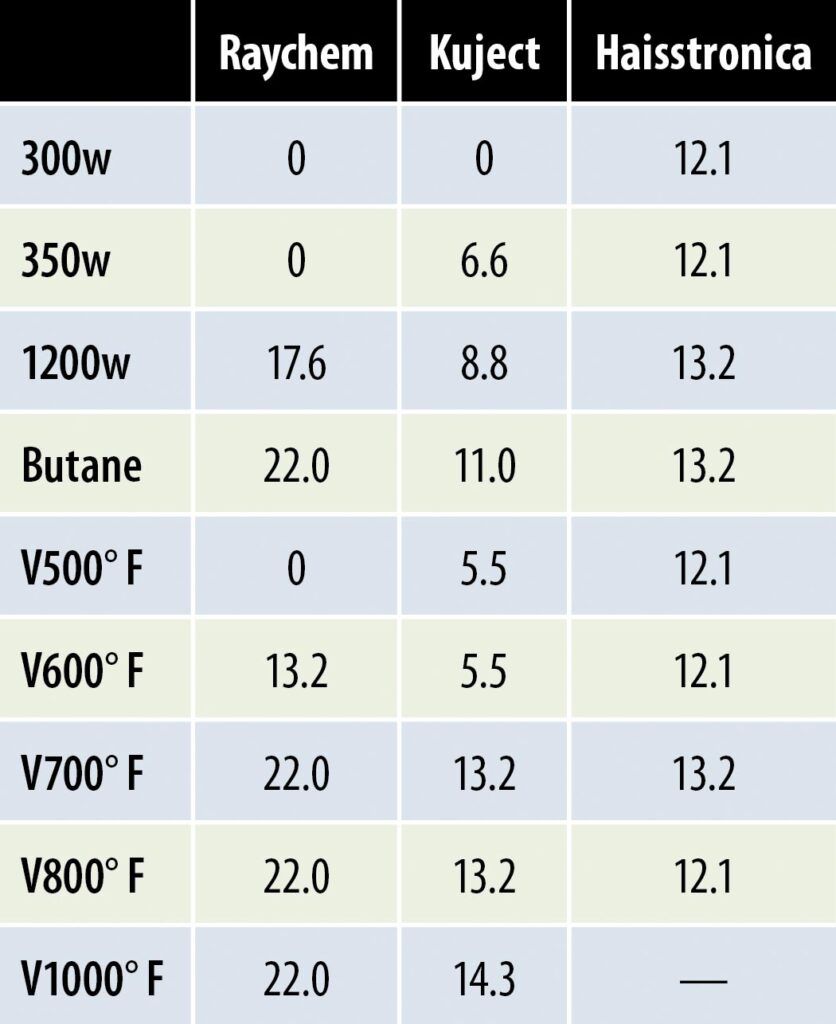

The table below shows the outcome of the visual tests, including minimum time required to achieve the indicated results. The variable-temperature gun is listed with a “V,” followed by the tested temperature (e.g., V500° F).

As a general rule, using higher heat is faster and generally achieves good flow-out, but requires a more refined technique to ensure the heat is evenly applied without charring the sleeve. Midrange heat levels take a little longer, but produce more consistent results without burning anything.

The Raychem and Kuject brands required more heat, with Raychem being more tolerant at the top end of the heat range. The 300-watt gun was insufficient for any of the brands. The 350-watt gun worked with Kuject and Haisstronica, but was not hot enough for Raychem. This is reflected in the lower temperature results with the variable-temperature Wagner gun as well.

The butane heat gun puts out a lot of heat but in a very concentrated area. With this gun in particular, it is necessary to keep it moving, lingering a little longer on the solder band, spending less time on the glue bands and less still on the parts of the sleeve without any solder or glue. The tests for this article consumed about half of the butane.

The larger heat guns put out a temperature similar to the butane gun but with more significant airflow, spreading the heat over a larger area and shrinking the sleeve a little more quickly as a result.

At higher temperatures, the Wagner gun would achieve fast flow-out but at the expense of some charring. More than 900° F is really too much for any of these sleeves.

Strength Test

For this part of the test, we wrapped one end of the wire around a pull gauge and the other end around a wrench in a vise. The readout on the gauge captures peak strain and records the point at which the joint breaks.

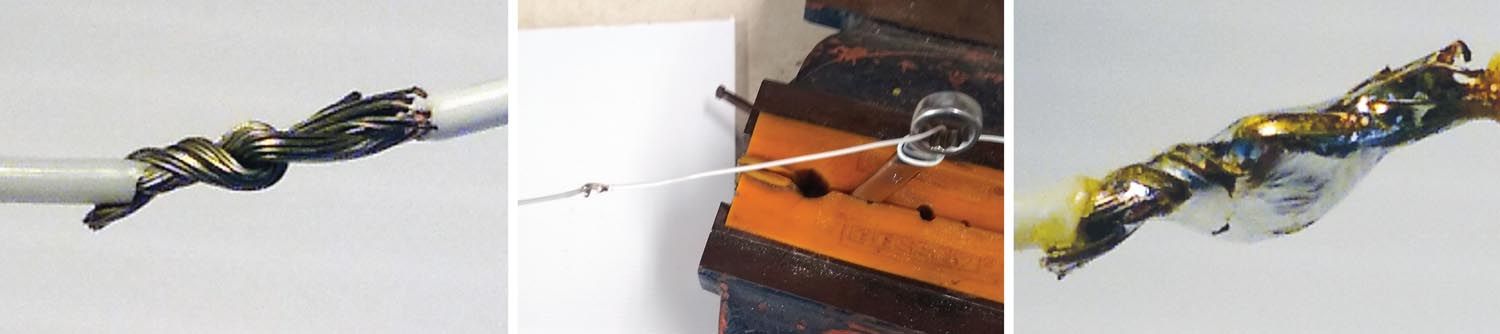

To establish a strength baseline, two splices of 22-gauge wires were made using normal soldering techniques. The first splice was a regular overlapped joint. It broke at the soldered joint with a pull of 19.8 pounds. The second splice was done by making a “hook” of each wire end and then wrapping the loose ends around the wire before soldering. This boosted the breakage point to 24 pounds.

Regular 22-gauge wire will break at about 24 pounds. When solder or solder sleeve makes it to this point, it is close to the ultimate yield strength of the wire itself.

In practice, a wire should never be subject to a stress of more than a few pounds, and this should only be while pulling the wire through a bundle or performing other installation or maintenance tasks. In operation, the bundle should be well supported, not subject to movement and the connections not subject to any appreciable tension. With this in mind, any sleeve with a pull-strength of greater than 3 to 4 pounds should be sufficient. However, at low heat the Raychem and Kuject joints fell apart before even registering on the gauge. In all cases, the guns that put out less heat required longer to achieve a satisfactory flow-out of solder and glue.

Analysis

Any of the solder sleeves brands can achieve acceptable results but only when matched to an appropriate heat gun.

Solder Sleeves

Raychem Sleeves: Achieved the strongest joints but required a moderately hot gun to work. They are the most expensive but have been around a long time.

- Pros: Very strong connections, thick insulating sleeve.

- Cons: Expensive, requires higher heat.

Kuject Sleeves: Provided visually acceptable joints at a variety of temperatures but generally achieved stronger joints at higher temperatures.

- Pros: OK performance, less expensive.

- Cons: Narrow temperature range to achieve best strength.

Haisstronica Sleeves: Achieved consistently strong and visually good joints over a wide temperature range but tended to char more quickly at higher temperatures.

- Pros: Consistent strength and visual results. Works at lower temperatures. Less expensive.

- Cons: More sensitive to higher temperatures.

Heat Guns

300-Watt Gun: Works fine for general heat-shrink jobs but just doesn’t put out enough heat for any of these solder sleeves. This might explain the experience of some builders who tried solder sleeves and then threw them away because they couldn’t get the solder to flow.

- Pros: Small and cheap.

- Cons: Insufficient for all solder sleeves tested.

350-Watt Gun: Takes a little longer but achieves good visual results and moderate strength with the Haisstronica brand. The advantage of this gun is that it is smaller and easier to work with in tight places.

- Pros: Small and fairly cheap.

- Cons: Not sufficient for Raychem sleeves and marginal for Kuject sleeves.

1200-Watt Gun: Worked reasonably well for all the solder sleeve brands but did not achieve peak strength for either Raychem or Kuject.

- Pros: Fairly cheap. Works for all brands tested.

- Cons: Did not achieve peak strength for two of the three brands tested.

Butane Gun: Achieved good results with all of the brands, but care is required to ensure the gun is kept moving in order to shrink evenly and avoid charring the sleeves.

- Pros: Small, portable, no electricity required. Worked for all brands tested.

- Cons: Consumes butane rapidly, requires good technique to avoid charring.

Wagner Furno 750 Gun: One of the more bulky solutions but provides the ability to tailor temperature and airflow to be optimal for the brand of sleeve being used.

- Pros: Variable temperature and fan control, can stand up on a workbench, good results with all sleeve brands.

- Cons: Most expensive of the guns tested, somewhat bulky.

Conclusion

Solder sleeves can be a great addition to your tool kit, providing a convenient way to splice wires and add pigtail grounds to shielded wire. The connections can be sufficiently strong and the end result is sealed and insulated from the environment.

The cost of solder sleeves has been a deterrent for some builders but low-cost alternatives are available now that can achieve good results at about 10% of the price of traditional sleeves.

In all cases, it is important to ensure that the right heat gun is used, as some sleeves will not work with some heat guns and in some cases, even if the result looks like it has worked well and may be electrically sufficient, it may not have achieved peak strength if the right temperature has not been applied.

If peak strength is a requirement, the Raychem brand with a hot gun will probably be the best combination. However, if moderate strength is acceptable, the other brands provide good alternatives. Haisstronica, in particular, can provide good results with less heat.

Other brands of sleeves and guns may work equally well or better than the ones tested. That’s what experimenting is all about!

Very interesting! I used a 1200W heat gun on a Kuject sleeve and then cut the solder joint. It was clear that the solder didn’t penetrate very deep into the strands, making me reluctant to use the sleeves at all. Next time I’ll use my mini butane torch.

The Raychem splices are, in my opinion, the best of the lot. The comment regarding melting temperature of the solder being higher for the Raychem should also note that Raychem makes splices with various melting temperatures.

Another tidbit is using infrared heaters for shrinking and melting. I’ve used an IR500 for years and it is both fast and easily controlled.

Lastly these splices are available in MIL spec versions for those that demand controlled manufacturing.

Ref. NAS1744, NAS1746, M83519/, etc.

Beware the large bargain box on Amazon variety. Many are complete junk. No glue component and no matter how good your technique and heat source – the shrink wrap chars long before the solder flows properly. YMMV

Excellent article. With regard to the last side bar about the “Third Hand”, it is a great bench tool. However, I may add that the sharp teeth of the alligator clip jaws can bit into wire insulation more than desired. The teeth could be filed down a bit before use. But instead of that time consuming process I suggest putting short lengths of heat shrink on each set of jaw teeth and shrinking it down. That creates a cushion so the teeth do not bit into the wire insulation. The heat shrink will wear and may have to be replaced on occasion but that’s easy.

Forget about it. They are terrible. I had a professionally built radio intercom harness built for me that used them. I had intermittent radio / intercom problems a few months after I built the plane. Finally removed the harness and half the wires just fell apart from those sleeves, and there was my intermittent problem. They all looked bonded from the outside. I made another harness with real solder and heat shrink tubing and it’s now several years without a glitch. I pity the poor soul that uses them extensively in a plane for all the electrics and sensors, I can’t imagine chasing down those gremlins. Don’t walk away run away.

Awesome article! Wish I had seen this before I did my project.

Ordered a variety from TEMU. Tried them, complete junk, into the garbage.

This is the most unscientific experiment ever with useless results. What is important to know has not even beed addressed. 1 what is the exact melting trmp of thr solder in the sleeves. Not the heat gun temp which has to penetrate the shrink tube . What is the melting point of the solder itself. This needs to be known because aircraft in the sun parked can get to internal temps of well over 140 degrees. If the solder melts at 125, you have a issue with long exposure heat. 2 at what external saturated temp does the bond break ? To know you put 1 lb force pull on the joint and place test jig in oven. Find out at what saturated temp the wires pull apart. It will surprise you. 3. I believe these sleeves are not good for airplanes at all where they experience high temp saturation parked in the sun. Im a former NASA technical director and scientist. These sleeves all use low temp melting point solder which is very bad in saturated temp high heat such as airplanes parked. They become ovens . The heat shrink thermal barrier to the solder that causes the need for high temp heat guns , is not a factor in saturated heat situations. The heat barrier becomes completely no issue to the solder reaching the external temp .